As promised, this week I want to do a bit more old-style seminar reporting. I’m not getting out to seminars the way I once did, and wasn’t even in early 2021, our current point in my backlog, but sometimes if you’re in the right place the seminars come to you, and sometimes Leeds is that place…

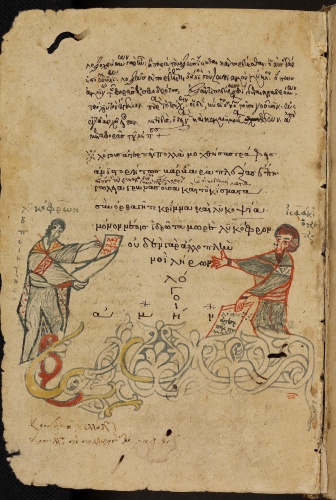

Heidelberg Universitätsbibliothek Cod. Pal. Grace. 18 fol. 96v, showing "Isaac" Tzetzes offering his Scholia in Lycophronis to Christ, this misnamed 13th-century depiction being the only one there is of our next subject

In the first instance that was slightly less surprising because the speaker was Dr Maroula Perisanidi, who had been working for us for some time by this point and was shortly to become an established member of our staff! But with that still in the future, on 26th January 2021 she was presenting to the Institute for Medieval Studies Research Seminar with the title, “Animals and Masculinities in the Letters of John Tzetzes”. I had not heard of this particular twelfth-century scholar before, but Maroula made him out as a very sympathetic character for an 21st-century western audience: he thought competitive warlike masculinity was silly (as do many of us who feel we would be bad at it, I guess, but that doesn’t always stop us responding to challenges…) and that real intellectual endeavour was a non-competitive and largely inward pursuit; and he was almost always short of cash or support.1 Furthermore, and Maroula’s key point, his letters are full of the love of animals: he hated hunting; he kept pets and mourned them when they died (and pointed to significant warleaders who had done likewise as proof that this was a perfectly masculine thing to do); and he argued that animals were better than people in lots of ways, not limited to but definitely including their superior senses. I did notice that in Maroula’s instances Tzetzes seemed most ready to liken himself to the phoenix, the lion, the kite, etc., rather than the mouse, louse or rabbit, but that doesn’t make his positions any less striking. Questions were naturally raised about whether he was weird, and to that Maroula reckoned that rejecting hunting was quite common but that in the rest of it he might be more unusual. Emilia Jamroziak reminded us of the trope in saints’ lives (and before, with Androcles and that) of the animals which help the worthy, but Maroula thought Tzetzes gave the animals their own agency in making his points; it was their normal animal life he used, not their narratively-necessary bits of interaction with humans. There was lots left to work out, and I guess that is still going on, but as what we might call "serious entertainment" this was a winner of a paper.2

Exterior of one church which certainly was rebuilt under Islam, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Photo by http://www.flickr.com/photos/jlascar/ – http://www.flickr.com/photos/jlascar/10350972756/in/set-72157636698118263/, licensed under CC BY 2.0 via https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30052661

The next paper I want to record was one that it’s possible I caused. At least, back in the days of physical meetings and the Institute for Medieval Studies Public Lectures, which went away during the high pandemic for obvious reasons and never came back, I put on one of the feedback sheets they used to hang out something to the effect of, “What about Janina Safran?” No-one subsequently mentioned this to me, but when I later learned that on 23rd February 2021 Professor Janina Safran was in fact presenting to the same seminar, with the title, "Reading Fatwas into History: ‘Let Every Religious Community Have its House of Worship’", I couldn’t help but wonder. In any case, Professor Safran, whose work on divisions and interactions between religious and social groups in Islamically-ruled communities has been quite important over the last few years, was doing some more of that, and her specific questions were about Christians and Jews being allowed to rebuild churches or synagogues, respectively, or indeed build new ones, where Islam ruled.3 It’s all too easy now to look this up and find someone citing that rather difficult pseudo-document, the Covenant of ‘Umar, as proof that this just wasn’t and isn’t allowed.4 But as Professor Safran quickly showed, there has never been agreement across Islam about this issue (or about what the Covenant of ‘Umar is, for that matter), and even if there had been, the mass displacement of communities from the collapsing Muslim states in the Iberian Peninsula to Africa and vice versa in the twelfth to fifteenth centuries (CE) would have brought the issue to a head as existing community resources were swamped or abandoned in each case.5 Professor Safran had found a range of Islamic scholars each with a different opinion: about the only thing they all agreed on was that bell-ringing was not allowed, but for some there was neither building nor repair allowed because Christians were a treacherous fifth column (apparently the opinion of Ibn Rushd, even though modernity loves to love him), for some repair but not expansion (al-Burzulī), for some necessary expansion but not new building (Ibn al-Hajj, Professor Safran’s main source for the paper) and for some even new building was allowed if no Muslims were there to see it (and likewise the only places bells were OK were where there were no Muslims to hear). And of course, all of this was coming before jurists because the thing was happening anyway and people were consulting them over whether it was legal, or we’d not have the fatwas (rulings); but that also means people weren’t sure. Since each specific pact with a Christian community was individually negotiated at conquest, as long as they had surrendered, there was even the question of whether general legal rules could or could not overrule particular concessions, and most agreed that they could not. We lost Professor Safran to internet patchiness before we got to the conclusion, but recovered her for questions and had by then already accumulated quite a rich picture of the bitty, cumulative and sometimes contradictory way in which Islamic law developed and develops. People who get worried about the iron force of sharīʿa might take some comfort from medieval illustrations like these of how it actually got and gets worked out in practice.

Mosaic floor in the 3rd-century synagogue at Kibbutz Ein Gedi, image from the Madain Project and linked through to them

Lastly, not a medieval paper at all but one which turned that way suddenly in questions, on 24th February 2021 another Leeds colleague, Dr Nir Arielli, was presenting to the School of History Research Seminar with the title, “Life Next to the Dying Dead Sea: a social-environmental micro-history of Kibbutz en-Gedi”. This, I attended largely because some months before Nir and I had warmly agreed that there needed to be more work on land use in the School of History and thus I felt that, when he was then doing that, I should probably support. The land use in question, however, is at great risk because of the way that the Dead Sea has shrunk over the last few decades, largely if not entirely because of extraction for industry from the River Jordan by many countries.6 The pictures were dramatic and worrying, but the hook for this medievalist listener came from the fact that, among its other work on the site, the Kibbutz has found and attempted to frame itself as the revival of a Roman-period Jewish village. This rang bells for me because of the work of Dan Reynolds about the historicization to political purposes of Roman- and Byzantine-period use of lands in these areas, but I restricted myself to asking how long the Roman settlement had lasted and what was known about it by the Kibbutz community.7 Even that was quite interesting: the site had a synagogue, with a mosaic floor that you see above which very handily identifies itself, a Cave of Letters connected with the Second Jewish Revolt whose records include the court cases of a a litigious second-century woman called Arbatta, among the other victims of the Roman suppression of the rebellion, and other remains that indicate the place was occupied until the seventh century. I don’t know what happened then and all likely answers would probably be bad at the moment, but it was certainly easy enough to understand why the modern community had built themselves a museum for this stuff and interesting that the past was so literally central to the place and its settlers’ identity. There were lots of other more relevant questions as well, of course, but I felt as if I’d got the medieval to show itself in my modernist colleagues’ work for a moment and therefore went away well satisfied as well as more educated. Which, I suppose, is ideal for a day in a university environment!

1. If one is in need of an introduction to Tzetzes, other than the man’s own X feed already linked of course, one might try Enrico Emanuele Prodi, "Introduction: A Buffalo’s-Eye View" in Prodi (ed.), Τζετζικλι Ερεϒνλι, Εικασμος: Quaderni bolognesi di filologia classica, Studi online 4 (Bologna 2022), pp. ix–xxxv, online here, but I admit I haven’t so can’t be sure what you’d get.

2. If you can’t wait till this emerges, you could sate yourself meanwhile with Maroula Perisanidi, "Byzantine Parades of Infamy through an Animal Lens" in History Workshop Journal Vol. 90 (Abingdon 2020), pp. 1–24, DOI: 10.1093/hwj/dbaa019; and the phrase "serious entertainments" is famous to me because of Nancy F. Partner, Serious Entertainments: The Writing of History in Twelfth-Century England (Chicago IL 1977).

3. Professor Safran was known to me when I scrawled that request for work such as Janina M. Safran, "Identity and Differentiation in Ninth-Century al-Andalus" in Speculum Vol. 76 (Cambridge MA 2001), pp. 573–598, DOI: 10.2307/2903880; Safran, "The politics of book burning in al-Andalus" in Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies Vol. 6 (Abingdon 2014), pp. 148–168, DOI: 10.1080/17546559.2014.925134; and Safran, Defining Boundaries in al-Andalus: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Islamic Iberia (Ithaca NY 2015).

4. See for example David J. Wasserstein, "ISIS, Christianity, and the Pact of Umar" in Yale University Press Blog 16 August 2017, online here.

5. Further doubts about the application of the Pact can be found in Norman Daniel, "Spanish Christian Sources of Information about Islam (ninth-thirteenth centuries)" in al-Qanṭara Vol. 15 (Madrid 1994), pp. 365–384, which includes apart from anything else a demonstration that there is no evidence for the Pact being known in al-Andalus.

6. See for more Nir Arielli, "Land, water and the changing Dead Sea environment: A microhistory of Kibbutz Ein Gedi" in Journal of Israeli History: Politics, Society, Culture Vol. 40 (Abingdon 2022), pp. 235–256, DOI: 10.1080/13531042.2022.2186311.

7. Daniel Reynolds, "Conclusion: Post-Colonial Reflections and the Challenge of Global Byzantium" in Leslie Brubaker, Rebecca Darley and Daniel Reynolds (edd.), Global Byzantium: Papers from the Fiftieth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Publications of the Society for the Promotion of Byzantine Studies 24 (London 2022), pp. 372–409, DOI: 10.4324/9780429291012-20 at pp. 376-391.