Bits of my Leeds paper are crowding in my head wanting to be written, and I don’t yet have anything like all the data assembled to do it (though if forced I could probably assemble a text tonight). What better tactic, then, but to offload some of the brain-twisting here?

The Leeds sessions that I and my collaborators run hit their third year this year; they’re called ‘Problems and Possibilities of Early Medieval Diplomatic’. The idea is to show firstly that charter evidence is subtle and complicated to interpret, and secondly what you can learn when you do interpret it carefully: the first bit is problems, and the second possibilities. Everyone else’s papers seem to be about the possibilities, and mine much more about the problems. It’s not that I don’t have stuff to say on the basis of my charters, as you know, but for Leeds, when I have a charter-savvy group to work in, I get much more interested in the basic questions we often forget to ask, of why we have the evidence, why it looks the way it does, whether what they were recording was real or just formulae, and so on, the basic text criticism and the methodology of it. And this leads me this year, heavens help me, to be messing with the charters of Cluny.

You see, last year when I was putting together this proposal, there obviously seemed to be all the time in the world, and so I cast about for diplomatic ideas, and came up with this. We know, and if we didn’t the work from the Lay Archives project would make it clear,1 that many charters exist in archives that appear to have had no interest in preserving them. By and large, of course, a Church archive preserves documents that relate to that church’s lands and donors, and this is most of what we have, but wherever the sample opens up a bit, things leak into preservation that don’t easily fit that scheme. Traditionally, these have been explained as background for donations that occurred later but whose documents have been lost, and that obviously has problems: why did they lose the important one and not the legacy one, why didn’t anyone throw out the useless one? Recently a couple of the people in the Lay Archives group, Warren Brown from his work on Bavaria and Adam Kosto from the Catalan stuff, have been suggesting that actually churches were functioning as kind of depositories, substituting in this way for the old Roman gesta municipalia but also just because the charters in question would often have been written by the local clerics anyway and might as well stay where they could be read. Adam also argues that whole lay dossiers of parchments were sometimes given into the care of the church in difficult times, and that does seem to be what’s necessary to explain the wealth of Church-irrelevant documents in Catalonia, where we know (because some of them still exist) that lay archives were kept.2

For some time this has seemed problematic to me. As with a lot that Adam writes, it’s so close to what I think that I find it hard to articulate my difference, but it seems to me that when a body of charters reaches a Church archive, it often does so because someone who has inherited or acquired the land to which they relate is now giving it to the Church. That is, both explanations were sometimes true at once: there are lay dossiers, and they’re given to the Church with land. But sometimes these dossiers include documents that are nothing to do with the land. So, for example, the first case of this I came across: there are in the Arxiu Capitular d’Urgell six charters from the late ninth century that feature a judge called Goltred. Five of them are purchases of land that eventually come to the cathedral, classic transmission if you will. The sixth however is a trial over which he presided, in which one man was set to pay compensation for breaking into another man’s house, beating him with a cudgel (the document makes it clear that part of why this was so bad is that it was the victim’s own cudgel) and then kidnapping and keeping him prisoner in a neighbour’s house for a week. Frustratingly, why the perpetrator did this is never explained, though the document does say he claimed it was done in self-defence! But anyway: the compensation is monetary, though paid in produce; no land is involved, and neither does the cathedral of Urgell feature.3 So I think the only reason that we have this is that one of the documents that came out of this trial went to the judge, by way of record, and when he finally gave his lands to the cathedral, they shunted all his parchments into the cathedral archive and no-one looked at them for about 1,800 years. Preservation by neglect, I call this, and I think there’s a lot of it.

Anyway, we have paradigms, they need testing, and this is where Cluny comes in. There are certain places where the charters preserved predate the actual archive institution’s existence. In Catalonia most places have one or two from ‘before’, and pinning the reason they’re there down is very hard because the string is so short. Four charters at Vic feature an extraordinarily long-lived Viscount called Franco, who seems to have ruled the mini-county of Berguedà in apparent independence. All of the charters are purchases, he doesn’t appear anywhere else, two of them predate Vic’s refoundation in about 885, two of them don’t.4 The lands didn’t identifiably come to Vic, and the only explanation that I can think of is that they were stored at some church in Berguedà of which the cathedral of Vic later acquired control. There’s no proof though. So I wanted to look elsewhere and see what the trends of this preservation are where we’ve got more of it. And there’s nowhere with more than Cluny.

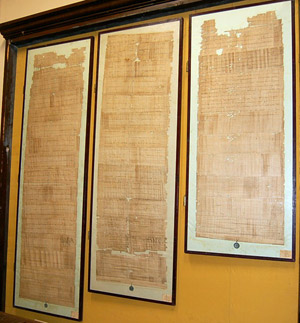

Cluny is a desperately important abbey for most of the High Middle Ages, but in early medieval terms it’s a latecomer, being founded only in 910. Its charter corpus, however, starts in 813, almost a century before, which obviously needs some explanation. I don’t have one, except that so much exists from Cluny, many thousands of charters (almost all of which now exist only in scholarly copies, but that’s the Franco-Prussian war for you), that it seems unlikely they ever really went through weeding the archive: once something came there it stayed. There is a classic edition of Cluny’s charters, but it never reached the index volume, so up till now really working with them has been difficult.5 Now, however, the various projects on Cluny being run from the University of Münster have resulted in a digital transcription of that edition, if you know where to look. So I have been steadily databasing this early stuff, and searching through the files trying to find out why they wind up with Cluny. (“Stand back! I know regular expressions!”)

It’s extremely frustrating. Sometimes they’re just singletons, neither place nor recipient ever seem to turn up again. They may well do, of course, because places change names and landholders bequeath stuff without writing it down but a broken trail is little better than no trail in this particular inquiry. As one advances towards foundation date, the trails get easier to follow, but even so one is often left going: “there’s the land in 880; here’s land in the same villa in 910 that seems to be bounded by the same geography in a couple of edges, but it’s bigger, and if it contains the same estate, if, how it got from Adalramn to this Ardeo geezer is just impossible to say”. They don’t name their parents, they don’t say how they got the land, you’re just stuck with this magic lantern now-you-see-and-now-you-don’t situation when you can see it at all. I’ve got some good cases where it does work out, and especially the royal ones are almost always really simple; this precept is here because the relevant estate is in the hands of the monastery via this person one generation later, sorted. But I’ve also got quite a lot just marked “no clues!”

All the same, I’ve got enough to work with; and I also have the monastery of Beaulieu, whose early preservation is basically one neat example piece of an aristocratic personal archive – but if you want to know more about that you should come and hear the paper.6 I have to leave something in the bag :-)

P. S. Here we see an instance of the phenomenon I realised while leaving a comment at The Rebel Letter; I never seem to doubt that someone will be interested in this stuff. After all, I’m interested; I can hardly be alone in this in a net population of however many numbers-with-many-zeroes…

1. I live in hope that some day the Lay Archives Project will actually publish something, but at the time of writing there is nothing that I can announce. For the opposite case, stressing the way institutions profile memory and record according to its use to them, see Patrick J. Geary, Phantoms of Remembrance: remembering and forgetting in the tenth and eleventh centuries (Princeton 1985).

2. Warren Brown, “When documents are destroyed or lost: lay people and archives in the early Middle Ages” in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 11 (Oxford 2002), pp. 337-366; Adam J. Kosto, “Laymen, Clerics and Documentary Practices in the Early Middle Ages: the example of Catalonia” in Speculum Vol. 80 (Cambridge MA 2005), pp. 44-74. Professor Brown’s work makes the more careful case that actually this only happened with big families storing their documents at their own foundations, but in areas that were more ‘document-minded’, as Julia Smith would have it (Europe After Rome: a new cultural history, 400-1000 (Oxford 2005), pp. 13-50, concept introduced pp. 45-46) it’s much lower-level than that, as I think this paper will partly show.

3. Cebrià Baraut (ed.), “Els documents, dels segles IX i X, conservats a l’Arxiu Capitular de la Seu d’Urgell” in Urgellia: anuari d’estudis històrics dels antics comtats de Cerdanya, Urgell i Pallars, d’Andorra i la Vall d’Aran Vol. 2 (Montserrat 1979), pp. 78-143, doc. nos 19, 22, 24, 25, 26 & 27; the hearing is doc. no. 24.

4. Eduard Junyent i Subirà (ed.), Diplomatari de la Catedral de Vic (Segles IX-X), ed. Ramon Ordeig i Mata (Vic 1980-1996), doc. nos 1, 5, 7 & 138.

5. This difficulty has not prevented some genuinely important work being done from them, most obviously Georges Duby, La Société aux XIe et XIIe siècles dans le region mâconnaise, Bibliothèque de l’École Pratique des Hauts Études, VIe section (Paris 1953, 2nd edn. 1971), repr. in Qu’est-ce que c’est la Féodalisme (Paris 2001) (of which pp. 155, 170-172, 185-195, 230-245 transl. Frederick L. Cheyette as “The Nobility in Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Mâconnais” in idem (ed.), Lordship and Community in Medieval Europe: selected readings (New York 1968), pp. 137-155) and Barbara H. Rosenwein, To Be The Neighbor of Saint Peter: the social meaning of Cluny’s property, 909-1049 (Ithaca 1989). The charters are edited in Auguste Bernard & Alexandre Bruel (edd.), Recueil des chartes de l’abbaye de Cluny (Paris 1876-1900), 6 vols, of which all the material I’m using is in vol. I.

6. Or just have at the charters yourself I suppose: the relevant edition is Maximin Deloche (ed.), Cartulaire de l’Abbaye de Beaulieu (en Limousin) (Paris 1859) and it’s free to download on Google Books.

Edit: it has been suggested to me that the questions here are hard to understand for non-specialists. Therefore, I have created this summary for the neophytes of diplomatic criticism: