Again, rather than alternate I’ll follow a seminar report with a seminar report, partly because at this point in the notional sequence I was lamenting dead entertainers but mainly because of the sixty pages of Italian already mentioned. It only advances the seminar backlog by one day, however, since on 18th March 2015 I was apparently back in London again, to see a then-fellow-citizen of the Midlands 3 Cities University Partnership do his stuff at the Earlier Middle Ages Seminar at the Institute of Historical Research. He was (and is) Stephen Ling and his paper was called “Regulating the Life of the Clergy between Chrodegang’s Rule and the Council of Aachen, c. 750-816″.

Contemporary pictures, or indeed any pictures, of Chrodegang are quite hard to find, which in itself tells us something about how important he was to the Carolingians, but to my surprise one Paul Budde has provided the Internet with a picture that is in some sense of the actual man, in as much as his mortal remains are supposedly in this casket in Metz cathedral!

Now you can be forgiven for never having heard of Archbishop Chrodegang of Metz—it’s OK, really—but in a certain part of the historiography of the Carolingian Empire, and specifically of its longest-lived impact, the Carolingian Renaissance, he has a great importance as a forerunner, a man with the vision to see what needed doing before the opportunity really existed to do it. What he thought needed doing, it is said, was a general tightening-up of discipline and standards in the Frankish Church, and especially of the lifestyle of cathedral priests, or canons (students: note spelling), and to this end he wrote a Rule for their lives which involved having no individual property as such, living off stipends paid from a common purse, as well as more basically necessary things like priests not carrying weapons in church and so on. All of this he was doing in the 740s and 750s when he was effectively number one churchman in the Frankish kingdoms, but its full impact didn’t really come around until the 780s and 790s when Charlemagne’s international brains trust developed very similar agendas that went even further and found Chrodegang’s Rule exactly the sort of thing they needed. So, at least, the conventional wisdom goes.1

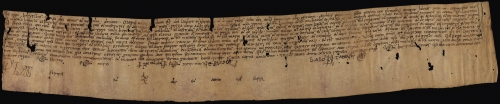

One reason for this conventional wisdom in English-language scholarship may not least be that the Rule was later picked up in England; here is an eleventh-century translation of it, London, British Library Additional MS 34652, fo. 3r, although that is the only leaf of it in the manuscript!

Well, of course, every now and then these things need checking. Mr Ling has been doing this, looking firstly into what can be verified of Chrodegang’s importance in the church of his days and secondly into the uptake, use and impact of his Rule, and it’s not looking as good as the archbishop might have hoped. It is only possible to verify his attendance at two of the five big councils he supposedly convened to sort out the Church, and he was not by any means the sole player at these events; Abbot Fulrad of St-Denis and Angilramn, Chrodegang’s successor at Metz, were not only also big names but lasted into the Carolingian period, so had a more direct influence on what was done then, both indeed being heads of the court chapel in their day. As for the Rule, well, firstly there are only four manuscripts of it surviving, two of which, significantly, were added to by Angilramn. More importantly, though, it is quoted only rarely, and most of the instances that Stephen had gathered were from Metz, which you might indeed expect but isn’t exactly widespread impact. It’s not that Chrodegang wasn’t known to the Carolingian reformers: Theodulf Bishop of Orléans used it in laying down rules for his diocese’s clergy and a council of 813 refers to the Rule direct, although it then goes on to apply part of it to parish clergy rather than canons. But it was not the only source of authority, with Isidore of Seville and Saint Jerome coming in much more often, and at times the Carolingian legislation flatly contradicted what Chrodegang had laid down. Compare these two, Chrodegang’s Rule and the Council of Frankfurt in 794 respectively:

“If we cannot bring ourselves to renounce everything, we should confine ourselves to keeping only the income from our property, and ensure that, whether we like it or not, our property descends to our not to our earthly heirs and relations, but to the Church.”2

“The relatives or heirs of a bishop should in no circumstances inherit after his death any property which was acquired by him after he was consecrated bishop… rather, it should go in full to his church. Such property as he had before then shall, unless he make a gift from it to the Church, pass to his heirs and relatives.”3

OK, it is true that the two don’t expressly contradict: a bishop, let alone a canon, could make a donation such as Chrodegang recommends and still be within the ruling of the Council, but the Council also allows for him doing exactly the opposite, as long as it’s not with anything that could be considered Church property. And this is kind of the way it goes with Chrodegang’s Rule: it’s a model way of being, but other ways are usually considered preferable. I’ve given only one of Stephen’s numerous examples, and I found the case basically convincing. It’s not so much that Chrodegang didn’t show the way: it’s more that, when someone has cut a cart-track through woodland and then forty years later the local authority widens, levels and grades it and puts tarmac down you can’t really trace the original route in any detail…

The replacement! The opening of a manuscript copy of the Aachen Rule for Canons of 816, it being Cologne, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 68, f. 6v

Indeed, looking back at it with ten months to reflect, I can see how perhaps Chrodegang’s lack of impact shouldn’t be surprising. The Carolingian reformers liked antiquity in their authority, and Chrodegang was a figure of living memory (indeed, died only two years before Charlemagne’s succession), one who had, furthermore, become a figure of importance under the notional kingship of the last Merovingian, Childeric III, whom Charlemagne’s father had deposed. It would thus have been awkward for the new régime to admit that, even with the help of the noble Mayor of the Palace and eventual replacement king, Pippin III, good things had been done then, rather than everything needing fixing.4 This is perhaps why rather than contesting the basic thesis, except for Jinty Nelson pointing out that a council of 791 comes a lot closer to Chrodegangian positions than the more definitive Frankfurt three years later, most of the questions revolved around canons, and whether they were at all usual or well-defined in the age that Chrodegang was legislating for. Was, in short, the reason this Rule mostly got used at Metz because that was one of the few places that had the relevant institution defined? Certainly, the eventual Institute of Canons laid down by Emperor Louis the Pious’s council of Aachen in 816 not only allowed for a lot of variety but closed even more down. In my metaphor of above, that was the tarmac, which just like many a modern road turned out to need continual patching and maintenance and probably went further than the old track. People working on that project did at least know the track had been there; but they also had other ideas.

1. Classically this position is developed in J. Michael Wallace-Hadrill, The Frankish Church (Oxford 1983), but there is now a much more detailed attempt in Michael Claussen, The Reform of the Frankish Church: Chrodegang of Metz and the Regula canonicorum in the Eighth Century (Cambridge 2004). [Edit: I should also have remembered to add to this the obvious starting point, Julia Barrow, “Chrodegang, his rule and its successors” in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 14 (Oxford 2006), pp. 201-212, DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0254.2006.00180.x.]

2. I take this from Mr Ling’s handout, which tells me that he took it from Jerome Bertram (transl.), The Chrodegang Rules: the rules for the common life of the secular clergy from the eighth and ninth centuries. Critical Texts with Translations and Commentary (Aldershot 2005), p. 78.

3. Again from the handout but this time from Henry Loyn & John Percival (edd./transl.), The Reign of Charlemagne: documents on Carolingian government and administration, Documents of Medieval History 2 (London 1975), pp. 61-62.

4. See Paul Fouracre, “The Long Shadow of the Merovingians” in Joanna Story (ed.), Charlemagne: Empire and Society (Manchester 2005), pp. 5-21.