When I promised you a post this weekend it hadn’t, I admit, fully dawned on me that that would be the New Year’s weekend. But I was ready, ready to give you a report on an interesting paper about Bishop John of Nikiu and the chronicle he wrote that is one of our earliest sources for the Islamic conquest of Egypt… and then I left the notes at home, so now that will have to be next week’s. Instead, let’s inaugurate 2024 by having a go at an erstwhile minister of government!

So, I stubbed this to write in May 2021 when Jo Johnson, brother of our lately-demitted Prime Minister whom one of my foreign friends calls Bojo the Clown, had just been promoted to the House of Lords after his second brief stint as Universities Minister. Lord Johnson of Marylebone, as he had thus become, was then back in the press for taking some strong lines in his speeches to the effect that academic links with China were bending academics’ and universities’ politics, as part of the Conservative party’s more general (and bemusing) preoccupation with limits on free speech on British university campuses. One of these got reported in an article in Times Higher Education that I read, but what caught me was not, sadly for Lord Johnson, his actual point but this quote from the article:1

“Lord Johnson called for a ‘Domesday Book‘ of research links with China to give ‘early warning’ of fields where ‘dependencies’ on China are emerging.”

And, as the kids used to say, I was like, huh.

Now, at one level it’s nice to see that someone’s default reference for a tool of use or an exercise of effective power is medieval rather than ancient or Victorian (or Churchillian). But is this a good one? It would be fairly easy to say, “well, that depends on what you think Domesday Book was for, doesn’t it?” It has been seen as a tax register, as a record of military service, as the final say on any issues of disputed land tenure (whence its name, from “Doom” as in judgement), (famously) as an ownership claim placed upon the entire country by William the Conqueror which put him at the top of all land tenure in it, and more recently (and compellingly) as a way of making almost all landed communities in the country gather to swear in solemn circumstances to the state of play on the ground at royal command.2 And it is probably quite important to realise that, whatever the actual inquest process of assembling that information was intended to do, the actual “Book”, which is (currently) actually four books plus related documents, representing at least three different levels of the recording process, none of them complete – and with no sign that London or Winchester were ever included at all – may well not actually reflect it terribly well.3

But of one thing we can be reasonably sure, which is that it was not an early warning system of any kind. I mean, I guess it might have been possible to comb through it looking for potential flashpoints of tension and then seek to avert them; but given the number of disputes that are recorded in it which we’ve no sign were ever addressed, I don’t think anyone has ever thought Domesday did in fact serve that purpose.4 And I guess therefore that Lord Johnson of Marylebone meant to invoke by his reference to it some kind of totally complete record which omitted nothing. But Domesday probably wasn’t ever that either (although Marylebone, as it happens, was included).

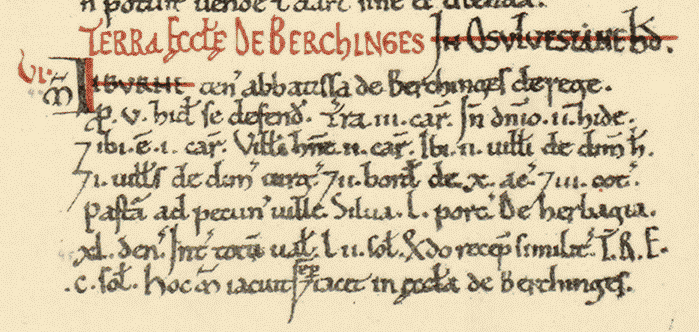

Domesday Book entry for the land of Barking Abbey at Marylebone, Middlesex, image from the Open Domesday project, linked through

But I’m not sure there’s any early warning to be derived even from that. Domesday was not a future-looking record; indeed, it covers so much that it must perforce have been becoming out of date even as it was written up. So my sad conclusion is that Lord Johnson, at least by 2021, didn’t really know what Domesday Book had been or was, or possibly even is. And perhaps that shouldn’t really be expected given that it must have been nearly thirty years since someone had taught him about it, even though he did get First Class Honours on a History degree which could have covered it, as I know because a mere seventeen years later I was teaching Domesday Book on that same course, with at least one person who must have taught his Lordship. I still think they might be a bit disappointed…

1. John Morgan, “Jo Johnson: self-censorship on China ‘biggest free speech issue’” in Times Higher Education (THE) (12 May 2021).

2. I remember well a seminar at the Institute of Historical Research n which John Gillingham said by way of preamble to a question that since retirement, one of the few luxuries he’d permitted himself was to stop keeping up with the scholarship on Domesday Book. I feel similarly about having left behind teaching England in 2015, and I’m conscious that the most recent references I have for any of this are a decade old. Plus which, it’s New Year’s Eve guys! So permit me just two references, David Roffe and Katherine S. B. Keats-Rohan (edd.), Domesday Now: new approaches to the inquest and the book (Woodbridge 2016) and Stephen Baxter, "How and Why Was Domesday Made?", English Historical Review Vol. 135 (Oxford 2020), pp. 1085–1131, DOI: 10.1093/ehr/ceaa310, and an assurance that between them you could gather at least where the debates stood quite recently. For much much more see David Roffe’s website…

3. Here see David Roffe, Domesday: the inquest and the Book (Oxford 2000), and the review by Stephen Baxter in Reviews in History (30th September 2001), online here, with Roffe’s response here.

4. Here I think I’d look at Robin Fleming, Domesday Book and the Law: society and legal custom in early medieval England (Cambridge 2003), but I’m conscious that Stephen Baxter thinks or thought that there was much about Fleming’s work on Domesday Book (including a book I think is great, her Kings and Lords in Conquest England (Cambridge 1991)) that stood in need of revision, and I don’t know if Baxter, “How and Why”, deals with that or if you’d be better looking in Stephen Baxter, The Earls of Mercia: lordship and power in late Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford 2007).