So, term started, and there was a short hiatus, for most of which this post was in draft. But, it’s actually a little hard to work out how to address the papers given at the Digital Diplomatics 2011 conference briefly. I don’t want to go on at the length of the previous post, and ordinarily therefore I’d start by listing the programme, but since it, the abstracts and indeed the slideshows from the papers are all already online, it seems as if you’d already have gone there if you wanted. Still, I can’t think of another structure, and maybe the few things I want to say will spark your interest, so I’m going to use my usual one anyway, but with a cut at the halfway mark because, well, this goes on a bit.

Systems

- Jeroen Deploige & Guy de Tré, “When Were Medieval Benefactors Generous? Time Modelling in the Development of the Database Diplomatica Belgica“

- Žarko Vujošević, “The Medieval Serbian Chancery: challenge of digital diplomatics”

- Richard Higgins, “Cataloguing medieval charters: a repository perspective”

This first session had been supposed to feature Christian Emil Ore, but he had now been moved to a slot later in the program, and Mr Vujošević moved up to compensate because of a later speaker not being available as planned. The organiser were keen on keeping papers together that could talk to each other. Dr Higgins’s was however, I think, always going to be an outlier: hailing from Durham University Library, which has a charter or two, although his primary concern was as most others’ getting stuff on the web so it could be used, he was trying to do so as part of a much larger project of which very little else was charters, and much of what he said of trying to find data schemes that would do it all struck close to my old experiences. It helped explain to the more hardcore audience, I think, why libraries so rarely seem to do things with charters the way that digital diplomatists might wish. The paper by Deploige and de Tré, meanwhile showed the kind of thing that we should be able to do with large-scale diplomatic corpora—things like, for example, did people give more to the Church when they were rich and there was peace, or when the Black Death was right around the corner?—but was actually more about quite how difficult it is to digitise medieval dates into something computers can actually compare. They had the compromise of a reference date, computer-readable and therefore unhistorically precise for the most part, and a text field always displayed with it showing the range of possible dates, but this is a kludge, I know because I do it myself, it leads to sorting of documents that may be completely awry, and they had a range of improvements they were hoping to try. And Mr Vujošević, meanwhile, spoke almost as a voice in the wilderness, because although Serbian medieval charters are plentiful they are very variably edited, if at all, and much of his work had turned into battles to simply get the texts out of archives and into a single uniformly-featured database. All the speakers were therefore giving work-in-progress reports on fairly intractable technical and archival problems, but I’m not sure this was the theme the organisers had expected to emerge.

Coffee, however, restored our spirits, and I was able to swap stories as well as some useful software tips with Dr Higgins, so the sessions resumed in good order.

- Pierluigi Feliciati, “Descrizione digitale e digitalizzazione di pergamene e sigilli nel contesto di un sistema informativo archivistico nazionale: l’esperienza del SIAS”

- Francesca Capochiani, Chiara Leoni & Roberto Rosselli Del Turco, “Open Source Tools for Online Publication of Charters”

- François Bougard, Antonella Ghignoli & Wolfgang Huschner, “Il progetto ‘Italia Regia’ & il suo sistema informatico”

The latter two of these papers were given in Italian, or so my notes suggest, whereas the first one, with an Italian title, was presented in English! Figure that one out. Anyway, I don’t speak Italian, and though I was surprised by how much I could muddle out of it by reading the English abstracts at the same time as they spoke, nonetheless I didn’t get much. I will just note that the second paper was actually presented by all three authors, in segments, whereas the last was presented by Ghignoli alone, a pity as I’d like to have met M. Bougard, he does things that interest me. The first paper, although I did understand it, was essentially a verbal poster for this SIAS program, which is slowly chomping through Italy’s national archives and cataloguing them all. Since some 20-25% apparently don’t have indices for their charters at all, some exciting stuff will doubtless come out of this but that wasn’t what the paper was about. The second paper I could follow more or less because it was essentially a how-to guide on publishing such material, a presentation that may have missed its audience here. The third was where my language really just wasn’t up to it and I don’t know if what was being said was a demonstration of a remarkable project or just another one, but the project is a digital database with images of all Italian royal charters, seventh to twentieth centuries, and if you wonder as do I about what the later end of that might even be I guess we can go look…

By now we were running some way behind, and there was a brief attempt to cancel the next coffee break, which had already been over-run. This was largely ignored—punctuation for the day, as I had that morning been told—but with some grumbling things were got going with some time clawed back, and we continued.

- Camille Desenclos & Vincent Jolivet, “Diple, propositions pour la convergence de schémas XML/TEI dédiés à l’édition de sources diplomatiques”

- Daniel Piñol Alabart, “Proyecto ARQUIBANC. Digitalización de archivos privados catalanes: una herramienta para la investigación”

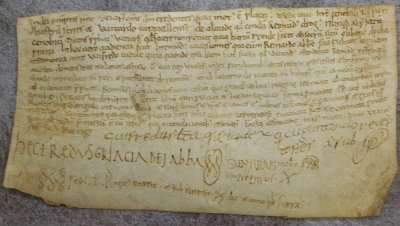

The former of these papers was notable for containing more acronyms and programming languages I think than any other at the conference, but this was partly because it was trying to explain the sheer variety of data schemas in use for charter material out there. By the end of this conference I think it was fairly clear to us all how this was happening: either new researchers don’t realise that there’s a toolset and a set of standards available to them and build their own, or, much more frequently it seemed (but then the former sort largely wouldn’t know about the conference, either…) they are aware of the tools but find them inadequate for their precise enquiry or sample and so modify them for their own purposes. The presenters argued that the widespread use of the TEI standard (explained last post but one) was making this easier for people to do, but that it also made it easier to link things back up again. The other paper, meanwhile, gave me great glee because it had my sort of material in it, documents in happily-familiar scripts and layouts, but what it also alerted me to was that for the period from when records begin in Catalonia to now, as a whole, a full 70% of surviving documentary material (of all kinds) is in private hands. Getting people to let the state digitise it, the point of the ARQUIBANC project, thus presents a number of problems, starting with arrant distrust and moving onto uncatalogued archives and getting scanners into somebody’s attic. Where this has been done, medieval material does come out, as indeed I knew from reading of the Catalunya Carolíngia for Osona and Manresa, where four of the tenth-century documents were revealed precisely by going and knocking on the doors of really old manors, but the size of the project as compared to the resources makes their considerable successes seem puny.

You will also imagine that I had much to ask Senyor Piñol, in shaky Catalan, afterwards on the subject of private archives, and he was helpful, but before very long we were being shuffled off to lunch, where I ate more pizza margarita than even I would have thought plausible in excellent company and felt pretty good about both these things on returning for the poster session and the last six papers. Continue reading