One of the things that marked Catalonia under Carolingian rule out from the rest of Charlemagne’s Empire was its continuing adherence to and use of the Visigothic Law that had run in the counties on the Franks’ arrival, and of course presumably since long before. We see this in two ways, procedural and textual. That is, people did things that we recognise from the law, such as the elaborate procedure of declaring a dead person’s will before judges or the losing party in a court case issuing a quitclaim or evacuatio disclaiming any right to take the suit up again; or else they invoke the law when doing things, often by specific chapter and verse but as often just as an idea, from which Roger Collins long ago got an article title, “Sicut lex gothorum continet“, ‘as is contained in the Law of the Goths’.1

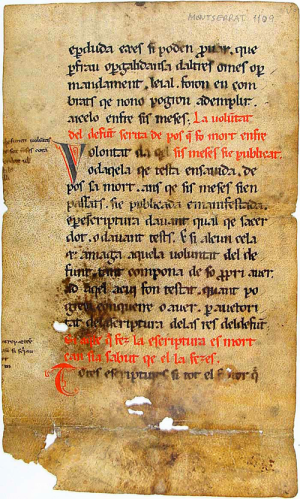

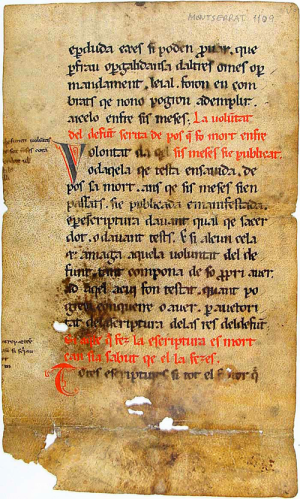

An actual Catalan copy of the Visigothic Law, Abadia de Montserrat MS 1109, from Wikimedia Commons

A decade ago already, Jeffrey Bowman added to this a sharp analysis of how selective and free-handed that quotation could be, however.2 A particularly common deformation is what is ‘contained in the law of the Goths’ about inheritance. Book IV Title 2 Era 20 says, as Bowman translates it: “Every freeborn man and woman, whether belonging to the nobility or of inferior rank, who has no children, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren, has the unquestionable right to dispose of his or her estate at will.”3 This is quoted relatively often at the beginning of donations to churches, and sometimes of sales although they tend to invoke other parts of the law, but when it turns up it always turns up with the bit about children and their descendants omitted. Thus what was originally a law that formed part of a block of twenty strictly regulating inheritance so as to prevent property-owners disinheriting their heirs through pious donation (or anything else) winds up being invoked to cover exactly that possibility. Bowman has other examples of this selective quoting, but what he has none of is cases where the people using the law actually write their own provisions into it, and that seems to be what I found towards the end of Catalunya Carolíngia IV.

This should probably have been spotted, in fact, because the document is in a small way famous. It records a gathering at the church of Sant Julià de Manresa (hitherto unrecorded) in March 1000, when in front of the judge Guifré a chap called Odsèn brought three people to swear under oath what had been in nine charters by which he and his wife Sabrosa held property, charters which had recently been lost in a fire. The level of recall is quite surprising, frequently flipping into the narrative person of the actual documents as if actually quoting, and calls to mind an earlier case of similar replacements in which the receipient of the property was said to have got them read out three times at the places involved, although since as I’ve shown that case was using a written model from elsewhere I don’t know quite how we explain what looks like the results of its procedures coming out here, eighty miles west and a a century later.4

There is basically no trace of the church of Sant Julià in Manresa now so the best I can do is tell you roughly where we are for this story...

We actually do have a good few cases of this, however, and it’s clear enough that a procedure existed to handle such losses that it has been given a name by legal scholars, reparatio scripturae.5 It was perfectly legal as far as Guifré was concerned, anyway, as we can tell because he says:

“And after I had heard and seen their numerous testimonies, I the above-said judge looked in the Law of the Goths, in Book VII, Title 5, Era 2, where it says:

‘If indeed they shall have burned in a fire any scripture required by law or stolen and burnt such a scripture, they shall give their professions in the presence of a judge and those professions be confirmed by witnesses, so that the lost or destroyed scriptures may be given force, or if most evidently what the scriptures contained cannot be recalled, then to those whose scriptures they were shall be given licence to prove them by their oath or by testimony’.6

This is, you may think, slightly creative, in as much as what that law seems to have been about is people like the Lombard Pando who famously burnt a document and was then forced to admit by a judge that, “If it had been favourable to me, I would hardly have burnt it”, that is, people who had destroyed their own stuff and needed to be called on it.7 Still, it obviously served Guifré’s purpose as well. Exactly how far Guifré had gone towards fitting the law to the case is however only evident if you actually go and check his citation. For convenience, here’s the translation of S. P. Scott, but the Latin can be checked at the Digtal MGH and he seems to be on the mark here to me:

“If any person should steal, or deface, a document belonging to another, and should afterwards confess, in the presence of the judge, that he had stolen or defaced said document, and this confession should be corroborated by witnesses, said testimony shall have the same force in law as the destroyed or defaced document would have, if it still existed in its integrity. But if the contents of the document cannot be shown with certainty, he who drew it up shall be permitted to prove by his own oath, or by a witness, what said document contained.”8

Now, the differences are partly only in translation: Scott, seeing that the fifth Title of Book VII is called “On Forgers of Documents”, obviously went fully out to make it clear who was to blame for what, and has used ‘confession’ for the word I’ve translated ‘profession’ and so forth; actually the Latin is not so far apart, except that there is no mention of fire in the original. Not one. There is Visigothic Law about stuff that gets lost in fires, but it wouldn’t have helped here and Guifré didn’t quote it. Instead he bolted in some extra phrases to the law, to the very written model he was invoking to justify the outcome of the case, to make sure it applied. (Or the scribe did, this is also possible but doesn’t take away the point, I think, since Guifré is said to have looked it up and found it there.)

Well, you may say, in a saving throw for Y1K Catalan jurisprudence, perhaps there were updated copies of the Law out there that did have this in; perhaps a seventh-century Ur-text established by the best models of German philological editing in the nineteenth century is not the best guide to what people were actually using hundreds of miles from Toledo centuries later. And this is fair enough: what we would really need is, if not Guifré’s own copy of the Book of Judges (for so the Law was called), at least a contemporary one and ideally one from the same judicial milieu. And as it happens we have one of those, copied by Guifré’s occasional colleague Bonhom, my official favourite scribe.9 Even better, there is a recent critical edition of one of them and better still than that, because this is reckoned one of the foundational texts of Catalan law, no less an authority than the Parlament of the Generalitat de Catalunya has stuck it on the open web for free. And this is all very useful, because actually here the Latin is even closer to what Guifré quoted, except that the bit about fire still isn’t there.10

A manuscript of the Liber Iudicum Popularis in the Biblioteca de l’Escorial, probably not MS Z.II.2 that we want here but all I can find on the web and probably nicer anyway

It’s hard to see this as forgery in our modern sense, or at least, it is for me. Guifré was not out to defraud anyone here: Odsèn and Sabrosa were in a pickle, they had no problem producing witnesses whose testimony was obviously more or less accurate, no-one seems to have been contesting their right to the lands, and it was Guifré’s job to put the cladding of proper legal process back onto their ownership of it. The law wouldn’t quite cover the case, so he edited it so that it would serve and so that everybody could have what they needed from the meeting. This is very much the model of medieval ‘forgery’ propounded by such luminaries as Christopher Brooke and Giles Constable long ago, where the intent was not necessarily to deceive but to supply evidence that was sincerely believed once to have existed for things everyone knew to be true.11 Here the evidence didn’t exist, but it was needed, so it was supplied. Nothing was lost from this, except perhaps the integrity of the law. But the big point here is that that is our idea of how texts and authorities work, not the medieval one in use here. So often we have to wonder whether ‘the medievals’ thought and reasoned the same way we did. It is useful, therefore, to be able to point at a concrete case and say: this was different, but it was different in a way that we can easily understand, if we choose.

1. Roger Collins, “‘Sicut lex Gothorum continet’: law and charters in ninth- and tenth-century León and Catalonia” in English Historical Review Vol. 100 (London 1985), pp. 489-512, repr. in idem, Law, Culture and Regionalism in Early Medieval Spain, Variorum Collected Studies 356 (Aldershot 1992), V; the milestone name in the Catalan historiography is Aquilino Iglesia Ferreirós, whose classic “La creación del derecho en Cataluña”, in Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español Vol. 47 (Madrid 1977), pp. 99-423, is now revised in his La creación del Derecho: una historia del Derecho español (Barcelona 1988), 3 vols, 2nd edn. (Barcelona 1989-1991), 3 vols; a shorter version of the early medieval part of his scheme is available as “El Derecho en la Cataluña altomedieval” in Federico Udina i Martorell (ed.), Symposium internacional sobre els orígens de Catalunya (segles VIII-XI) (Barcelona 1991-1992), also published as Memorias de le Real Academia de Buenas Letras de Barcelona Vols 23 & 24 (Barcelona 1991 & 1992) and thus online here, II pp. 27-34.

2. Jeffrey Bowman, Shifting Landmarks: Property, Proof, and Dispute in Catalonia around the Year 1000, Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past (Ithaca 2004), pp. 33-55.

3. Karl Zeumer (ed.), Leges Visigothorum, Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Leges Nationum Germanicum) I (Hannover 1902, repr. 2005), transl. S. P. Scott as The Visigothic Code (Boston 1922), IV.2.20, quoted with modifications Bowman, Shifting Landmarks, p. 40.

4. The document here is Ramon Ordeig i Mata (ed.), Catalunya Carolíngia IV: els comtats d’Osona i Manresa, Memòries de la Secció històrico-arqueològica LIII (Barcelona 1999), 3 vols, doc. no. 1840; the previous case is ibid., doc. nos 33 & 34, on which see J. Jarrett, “Pathways of Power in late-Carolingian Catalonia”, unpublished Ph. D. thesis (University of London 2005), online here, pp. 49-53.

5. A term first coined by José Rius Serra, “Reparatio Scriptura” in Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español Vol. 5 (Madrid 1928), pp. 246-253; see now Bowman, Shifting Landmarks, pp. 151-164, pp. 155-156 covering the point I make here but not this case or its special characteristic.

6. Ordeig, Catalunya Carolíngia IV, doc. no. 1840: “Et posquam audivi et vidi sua plurima testimonia supradictus iudex inquisivi in lege gotorum in liber septimus, titulus quintus, ers secunda, ubid dicit: «Si vero alicuo iuri debitam scripturam ad ignem concremaverint aut eandem scripturam substraxisent vel concremasent coram iudicem suas professiones depronant quod professiones ad testibus roboratas, perdiates vel vinciatas scripturas robur obtineant, quod si evidentisime quod scripturas continebant recordare non potuerint, tunc illis quibus scripturas fuerint habeant licentiam comprobare per illorum sacramentum vel per testem».”

7. For details and analysis see Antonio Sennis, “Destroying Documents in the Early Middle Ages” in J. Jarrett & Allan Scott McKinley (edd.), Problems and Possibilities of Early Medieval Charters, International Medieval Research 19 (Turnhout 2013), pp. 151-169, the case instanced at p. 151 with reference.

8. Admittedly, the Latin can’t be checked at the dMGH right now, because it seems to be down, but when I first stubbed this post and did the checks for it at the end of July 2012 (argh) it checked out fine then. The translation is from Scott, Visigothic Code, VII.5.2.

9. On him see Bowman, Shifting Landmarks, pp. 84-99.

10. Jesús Alturo i Perucho, Joan Bellès, Josep M. Font Rius, Yolanda García & Anscarí Mundó (edd.), Liber iudicum popularis. Ordenat pel jutge Bonsom de Barcelona (Barcelona 2003), VII.5.2: “Si uero alicuo iuri debitam scripturam subtraxerint aut uiciauerint, eandem scripturam subtraxisse uel uiciasse coram iudice sua professione depronant, qua professio a testibus roborata, perditae uel uiciatae scripturae robor obtineant. Quod si euidentissime quid scriptura continuit recordare non potuerint, tunc ille, cuius scriptura fuit, habeat licentiam comprobare per sacramentum suum aut per testem…”

11. Christopher N. L. Brooke, “Approaches to medieval forgery” in Journal of the Society of Archivists Vol. 3 (London 1968), pp. 377-386, repr. in Brooke, Medieval Church and Society: collected essays (London 1971), pp. 100-120; Giles Constable, “Forgery and Plagiarism in the Middle Ages” in Archiv für Diplomatik Vol. 29 (München 1983), pp. 1-41.

52.455160

-1.887498