I’m not sure how true this is in this third decade of the twenty-first century, but if like me you were first learning about the Carolingian empire of Charlemagne and sons in the last decade of the previous one, you probably didn’t get far before you encountered the name Karl-Ferdinand Werner (1924-2008). Some of the really major studies of how that empire worked, administratively, came from his pen or typewriter, and he always seemed to be capable of understanding that the administration had to rely on and even create loyalty to operate, and so made affective response as much part of his thinking as procedures and law.1 He was, in short, quite important in the field, had a very interesting career between Germany and France, and was respected in both, and this post is not intended to diminish his legacy in any substantial way. It is just meant to suggest that like sadly far too many historians, he was far safer with words than with numbers…

The evidence for this comes from a conference paper he gave at the annual Settimane di Studio held at Spoleto by the Centro Italiano di Studi sull’alto medioevo, in 1967. So he was a little bit younger than I am now, for whatever that may be worth, and surrounded by the great and good of the field of that time, and the theme of the year’s conference was matters military. The reason I was reading this, back in 2021, was because after you get more than a couple of works deep, almost everything there is on the vexed question of how much of the population went to war in the post-Roman kingdoms of Western Europe cites or even just rests on the papers presented at this nearly sixty-year-old conference, and Werner’s perhaps most among them.2 So I was a bit surprised it was as free-flying as it is, since I had never read anything else by him that suggested he could jump so far from his evidence. And since I have a pedigree in calling account on bad numbers in history, and since this can’t go into my article on this whenever it finally comes out, I thought perhaps it would be entertainment for my erudite readership here.

What Werner really wanted to know is something that others have wanted to know since as well, and if David Bachrach is reading, well, thank goodness you did that work, Professor Bachrach, as certainly no-one should have let things rest where Werner did.3 The object of enquiry was the size of army that the Carolingians’ successors in Germany, the dynasty we call the Ottonians, could put into the field, and Werner wanted it to be big; his paper had been provoked by a work by a guy called Delbrück which wanted to minimise the war effort of which these sub-Roman kingdoms were capable, and to which Werner thought a response was needed.4 His starting point was a document from Salzburg called the Indiculus Loricatum, roughly ‘List of Armoured Men’, which does actually give some viable figures for an Ottonian call-out, probably in 981 (though Werner thought 983), and it’s a better source than we might hope to have.5 But it doesn’t quite deal with the situation Werner wanted, and so it had to be, well, stretched…

What it’s not

The problems Werner faced lie in what the Indiculus isn’t, some of which are obviously related to what it actually is. So, for example:

- It seems to be a count of troops summoned to a campaign in Italy by Emperor Otto II, which means it’s not a call-out for the defence of Germany by Otto I, which would probably have been as close to a theoretical maximum as the numbers for service ever got. (One of the odd things about this paper is that it was in pursuit of that theoretical maximum despite occasionally admitting that that probably never happened).6

- It is a count only of armoured cavalry, which means it is possibly not a count of all the soldiers going, which one might expect to have included infantry, though I’ll come back to that.7

- It is a levy primarily from Saxony, which means it is obviously not the figures for the whole empire.8

- It is clear that not even all the known Saxon nobles were called, so that it’s not even a full levy from Saxony.9

All of that, of course, means that the figure it gives, which by Werner’s mathematics was 2,112 cavalrymen – remember that number, now – is necessarily a lot smaller than the figure Werner was after would have been. (It doesn’t help that the actual total seems to be 1,972.)10 And so the struggle begins to multiply it up to the "right" figure. Now, you know how I feel about this probably, but in case not, let me just quote once more the words of the late, great, Ted Buttrey:

When we enter on these kinds of calculation, we can be confident of two things. First, the answer will be wrong. Whatever it is, it will be wrong, since it cannot be right—once you are guessing, the number of possible permutations is gigantic. Worse, where the errors lie, and how serious they are, cannot be determined…11

And if we needed another example, this paper was it. Let me break it down, take it to the bridge and generally set the funk out (if I may)…

Multiplying up

How then shall we compare thee, o Indiculus, to a hypothetical full-scale imperial mobilisation? Let me count the ways.

- Firstly, we adopt a method already used by the rather later, but also great, Ferdinand Lot, who took early modern administrative divisions in France and their populations to give something like accurate multipliers for the fragmentary French records he was using for a similar, more pessimistic, exercise.12 Werner had some really quite good figures for known palaces, cities, fiscs and so on in Germany, and so some basis to repeat that, but…

- … they weren’t comprehensive, so he imposed an additional percentage as a guess for how many might not be included. First arbitrary alteration of the data…13

- The Indiculus figures also didn’t account for people who would not turn up, and neither did Lot’s.14 Firstly, obviously, we can’t know what that percentage in fact was, as this document only sets out what was expected, but it should make the real figure for turn-out lower than the Indiculus ones, you’d think; but Werner actually used this flaw as his excuse to go for the theoretical maximum hereafter.

- Then, going back to his early medieval administrative divisions, of course Werner didn’t have population numbers for these places as Lot had had from his anachronistic but proportional ancien régime data. So Werner just guessed, I’m afraid.15 Second arbitrary alteration…

- This had already got him to an empire-wide figure of 30,000 heavy cavalry that we can’t trust, but it was still only heavy cavalry, so he multiplied that by 3 to add the infantry. No basis for that multiplier was apparently thought necessary; just 3, you know, sounds about right.16 Third arbitrary alteration…

- Now, the Italian campaign factor. Here he made several assumptions: that troops would have been left at home for defence (extremely likely, I’d say, but of course unquantifiable except by step 1 above and that not really), that the campaign really was that of 983, not 981, and that therefore troops already sent to Italy in 982 might still be there, for a further discount; and that the nobility who are not listed should actually be included, even though the author of the source obviously didn’t think so. All of those, of course, need numbers making up to patch the gaps…17 Arbitrary alterations four, five and six.

- And lastly, because apparently none of this was enough, at around the twenty-five-page mark, the base number he got from the Indiculus in the first place, 2,112, suddenly becomes 4,000 for no obvious reason and without remark, which of course nearly doubles all his subsequent sums!18

But what if… ?

So just by way of illustration of where this gets us, we start with that actual early medieval figure of 2,112 people we could maybe even call knights, whom we know were expected to go to Italy, maybe in 983, on the emperor’s command, mainly from Saxony, and probably not all of whom did. By the time Werner had finished stretching this that expedition had become a force of 20,000 men, which as Carlrichard Brühl pointed out (and others have since repeated, mainly the late and also great Timothy Reuter), means that some of the armies we’re talking about exceeded the populations of most medieval cities.19 The potential error is therefore rather more than a full order of magnitude, but of course as Ted observed, we have no idea what it actually is. Werner could even have been right about all this, though I think the top end of the range is unlikely. But that is only to apply my own subjectivities in balance against his, and his basic assumption that the person responsible for the service would have brought people with him in support is probably fair. I am therefore temperamentally inclined to agree that the Indiculus isn’t a full picture, but…

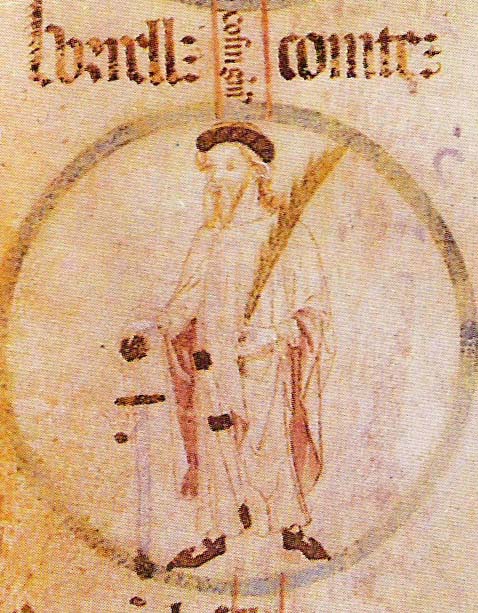

Speaking of full picture, here is the actual thing, Bamberg Staatsbibliothek Msc. Patr. 107 fo. 1, manuscript of the Indiculus Loricatorum, which was written into the leading blank page of a codex otherwise full of theology, largely Augustine. Image from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek MDZ, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

But let’s, just for a moment, try the counter-case. A different highly-respected German historian of this period, Hubert Mordek, once wrote another of my favourite methodological quotes, „[M]an muss der Überlieferung immer die Chance geben, recht zu behalten“, which we might translate loosely as, “You always gotta allow for the possibility the sources are just right”.20 And the source says, 2,112 mounted soldiers with mailcoats, almost all from Saxony. Not just that, either: Werner brought in numerous other sources from later or different German contexts to suggest that this was, indeed, roughly the sort of level at which kings in Germany could demand such service; another weird thing about this paper is that it itself gives you all the tools you need to dismantle it.21 So what if it is right? What if it was 983, there already was an army in the field in Italy, and Otto II felt it was necessary temporarily to weaken defence in Saxony and raise what could be raised from there to supplement the Italian force, with strictly mobile troops who could therefore get there soon enough to make a difference? What if therefore it was actually only cavalry and supporting grooms and so on that went, and from there and in that number because that was all they could safely levy? What if this was the operational maximum? It does still imply quite a large Ottonian army in total, what with a presumably-larger force in Italy with an infantry component and remaining defences in various places; but it doesn’t require us to think that an Ottonian Germany already at war could suddenly fling another 20,000 men at the problem. And I’m not saying that caution is right either. I’m just saying it’s a way way simpler conclusion than the one Werner reached which requires no messing with the numbers. And those, by and large, are the conclusions I prefer.

1. I guess I think here especially of K. F. Werner, "Missus – Marchio – Comes: entre l'administration centrale et l'administration locale de l'empire carolingienne" in Werner Paravicini and Karl Ferdinand Werner (edd.), Histoire comparée de l'administration (IVe–XVIIIe siècles) (München 1980), pp. 191–239, reprinted in Werner, Vom Frankenreich zur Entfaltung Deutschlands und Frankreichs: Ursprünge, Strukturen, Beziehungen. Ausgewählte Beiträge: Festgabe zu seinem sechzigsten Geburtstag (Sigmaringen 1984), pp. 121-161.

2. K. F. Werner, "Heeresorganisation und Kriegführung im deutschen Königreich des 10. und 11. Jahrhunderts" in Ordinamenti militari in Occidente nell'alto medioevo (Spoleto 1968), 2 vols, vol. II pp. 791–843 with discussion pp. 849–856.

3. Referring here of course to David S. Bachrach, Warfare in Tenth-Century Germany (Woodbridge 2012).

4. Werner, "Heeresorganisation und Kriegführung", p. 813, referring to the original publication of Hans Delbrück, Geschichte der Kriegskünst in Rahmen der politischen Geschichte, 2nd ed. (Berlin 1920), 4 vols, transl. Walter J. Renfroe Jr. as History of the Art of War (Lincoln NB 1975), 4 vols, vol. II in both editions, the German 1st ed. being in the Internet Archive here.

5. Printed as “Indiculus loricatorum Ottoni II. in Italiam mittendorum” in Ludovicus Weiland (ed.), Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Constitutiones et acta publica imperatorum et regum) I (Hannover 1893), pp. 632-633, online here, transl. W. North as “Indiculus Loricatorum (Index of Armored Contingents)”, Amazon Web Services, online here.

6. Werner, "Heeresorganisation und Kriegführung", pp. 823-824 and 817.

7. Ibid., pp. 820-821.

8. Ibid., pp. 831-832.

9. Ibid., pp. 806-808.

10. Ibid., pp. 817-819. The lower total I get by adding the figures given by North, “Indiculus Loricatum”. I probably should have added them myself from the manuscript, but come on guys, this is enough work already.

11. T. V. Buttrey, "Calculating Ancient Coin Production: Facts and Fantasies" in Numismatic Chronicle vol. 153 (London 1993), pp. 335–51, on JSTOR here, at p. 349.

12. Ferdinand Lot, L’art militaire et les armées au Moyen Âge en Europe et dans le Proche Orient (Paris 1946), 2 vols.

13. Werner, "Heeresorganisation und Kriegführung", pp. 817-820.

14. Ibid., p. 816.

15. Ibid., p. 820.

16. Ibid., pp. 820-821; he repeated this argument pp. 833-834 with a reference to an eleventh-century French call-out from Moyenmoutier where each knight was accompanied by a manus, a hand, of other troops, but that was somewhere else somewhen else and still doesn’t specify 3 as a multiplier.

17. Ibid., pp. 824-826 & 831-832.

18. Ibid., p. 829.

19. 20,000 men: ibid., p. 829; Brühl, in discussion p. 851; Reuter, in "Carolingian and Ottonian Warfare" in Maurice Keen (ed.), Medieval Warfare: a history (Oxford 1999), pp. 13–35.

20. Mordek, "Karolingische Kapitularien" in idem (ed.), Überlieferung und Geltung der normativer Texte des frühen und hohen Mittelalters (Sigmaringen 1986), pp. 25-50 at p. 30.