Yesterday and today, dear readers, I have been and am on strike again, because in short none of the promises that were made to stop me and my comrades striking last time have in the end been fulfilled, so we have had to come out again to try and get across that this will keep happening if the people in charge don’t in fact deliver some kind of reasonable attention to their staff’s problems. Indeed, it is not just keeping happening, it is escalating! Last time there were sixty-odd universities; today, and tomorrow and next Wednesday, every university in the UK has picket lines up, we are all out, and not just the academics but also the other two staff unions; the whole show is stopped. Admittedly, so is every school in Scotland, so we’re struggling for attention a bit; but it’s all the same disease, public-sector workers being asked to do more than we can for less than we used to be paid and much less than we deserve for the work we put in. So today that work stops, and you get an extra blog post.

Reconstruction of fifth-century Sandby Borg, Öland, from ‘Viking Murder Mystery’, in Ancient Mysteries, Series 4, episode 2 (London, 15 Dec. 2021), on freeview here

So this is all based on a bit less knowledge than I’d like, and some of that is my own unwillingness to find out more, which I’ll explain. But you might just remember that in November 2019, still a few months before the pandemic deluge, I briefly posted that I was going to be on television. That did happen, in the USA on the Smithsonian Channel, and much much later it seems that it did also come out in the UK on Channel 5, though no-one warned me so I couldn’t tell you. I’m still not sure when it was screened here – IMDB and Channel 5’s own site disagree – and I’ve no idea how many people saw it; all those I dealt with at the relevant company, who were all pleasures to work with, seem to have gone and I can’t get answers from the new ones. The previous incumbents did at least early on send me a video link, but I confess I haven’t ever dared look at it in case I came across like a buffoon (or worse, perhaps, a ‘boffin’), and the link is in my University e-mail which, because of the digital picket, I’m not opening. So I don’t know how much I was in it or what selection of what I said they used. A couple of people have mentioned seeing me on TV, and that must be this, but they couldn’t remember anything much about it, which doesn’t bode well… But I can tell you what it was all about, and that is a story worth telling.

Our location, then, is a place on the Swedish island of Öland, a place called Sandby borg, and the date is, well, that’s a question but let’s say after 425 and before 600 CE, and we can narrow it down in a moment. Sandby borg was not really known about until 2011, when it was first dug by a small Swedish archæological team, and what they found proved quite surprising.1 The place had been a fortress settlement, and whatever it was defending against, it had failed: the place had been breached and ruined, and there were slaughtered bodies aplenty. Some, even, had apparently been placed deliberately across the thresholds of houses before the dwellings were torched. But what had not happened was looting; though smashed, scattered and what-have-you, the material treasures of the site, weapons, ordinary belongings, metalwork, had been left where they fell, and then fires set. And then, apparently, the attackers left and no-one ever came back to it again. It’s really something like the murder and burial of a place. It disappeared under the sands and was left as it had been left at the point of the sack, until found again in “our times”.2

Drone photo of the dig under way, from the team’s Facebook site, linked through

Now, you may imagine that at that point the archæologists involved realised that they were sitting on something hot, and the press got involved and so, at some remove or other, did a company called Blink Films who, among many other things, do or did content for series about historical mysteries. Most of what they do is more esoteric, shall we say, than this, but when you have actual mystery any publicity may be good publicity, I guess, and so Blink Films picked this up and went looking for experts. And, because among the finds left to lie unstolen at the site were two Roman solidi of Emperor Valentinian III (r. 425-55), or so it seemed (more on this in a moment), one of the experts they needed was a numismatist, and they found me. So I agreed to be involved, and roped in the Barber Institute, where the now-Curator Dr Maria Vrij very kindly let me and a film crew back into my old workplace and we got out some more such solidi and I tried to sound like an expert about how the ones at Sandby borg might have come there and what it meant that they had.

I did have pictures of the coins, but I seem to have filed them somewhere ‘safe’; instead, here is one of them, and I think it’s the imitation, in its state of discovery (or a plausible reconstruction thereof), again from the team’s Facebook site

Now, at that point I’d had about four days to read up, and that during term, so I did not know all I wanted. But I had already learnt that, firstly, late Roman coins are not uncommon finds north of the Baltic, or indeed in the northern lands beyond the Empire in general, and that they are usually explained as payment for military service, brought home by the successful soldiery.3 I’d also learned, however, that apparently this set up a sufficient demand for such gold coin in at least what’s now Sweden that it became worth making your own, because a good part of the ones which we have are imitations.4 Whether that means that there were was a circulating economy of gold coin in Scandinavia this early, or that people outside the Empire were hiring Geats as soldiers and paying them in knock-off coin when the real stuff ran short, I didn’t have time to consider; but I could say that the likely context of these coins was military service, probably under Rome, and that one of the two finds here was probably an imitation, and I got to wave real ones at the camera and talk about the differences I saw and I hope, I hope, that that’s what’s in the programme. I think I also offered a theory about what had happened to the fort, but at this remove I can’t remember what I knew and what I only found out later, so can’t safely guess what that theory would have been. I can tell you what it is now, though.

Both sides of a real gold solidus of Emperor Valentinian III struck at Ravenna 426-430 CE, Barber Institute of Fine Arts LR0540

The important difference between what I knew then and what I came to know, you see, is a book by one Joan Fagerlie called Late Roman and Byzantine Solidi Found in Sweden and Denmark.5 I had started it, I had it with me and I think that’s where I had the idea of imitations from, but at point of filming I’d had no time to do more than open it and check some lists. It was sufficiently interesting, though, that I read all through it and realised that whatever I’d said on camera probably wasn’t wrong but could have been a lot better, because actually Sandby borg, both in its having these coins and in its untimely murder, turns out to have been part of a bigger phenomenon and it’s all, as my inner hippy still sometimes says, pretty heavy, man.6 These are the things I learned from Fagerlie and the other reading I also did:

- This coin flow was a long-term affair; even when Fagerlie was writing there were nearly 800 known coins (and of course there are now more), and their dates of issue ranged from 395 to about 600 CE, Theodosius I to Maurice, but with a very sharp falling-off after Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565). After that, indeed, Scandinavia was more or less the same as the rest of Western Europe, which basically stopped seeing imperial coinage in the troubled reigns of Phocas and Heraclius.7 But before that, it had something specific going on.

- Fagerlie then did a bunch of very clever deductions from the 726 of the 800-odd coins she had been able to look at. First she observed that the coins largely came from Constantinople, but also from some western mints, suggesting a flow from both halves of the Empire, and secondly she thought that it began under Emperor Leo I (r. 457-474), with anything earlier being stuff picked up from circulation (including lots of Valentinian III). And she noted that this period of maximum flow, from around 461 to about 550, pretty much coincides with when the Ostrogoths were a military quantity in the Roman Empire and then their own, but kind of not their own, kingdom of Italy. So the first clever deduction was that somehow the Ostrogoths were feeding this coin, which they perhaps obtained in tribute or salaries from the Empire, northwards, and that seems hard to dismiss.

- Secondly, she worked on distribution and die-links, that is, sets of coins which were struck using the same dies. This corpus is actually busy with die-links, which can only easily be explained by the coins involved having got to the north almost direct from the mint; they must have been shipped, received, paid out again and transported (apparently not through Italy but the Balkans and points north, scatters of incidental finds along the route suggest) and finally redistributed almost without being mixed with anything else. That’s interesting in itself, and tends to confirm the idea that these were state payments of some kind. Furthermore, the die-links start with the coins of Leo I, which also tends to confirm that that was a threshold of some kind and that earlier coin only came there from his time onwards. But this also lets one do something quite serious with distribution, because when you find coins with die-links that are a bit scattered, in this situation you can reasonably hypothesize that they arrived together. But where? And that’s where our stories recombine.

- You see, the die-links and distribution together, as Fagerlie saw it, paint a clear pattern of successive, single points of distribution into Scandinavia. The last, where the flow of coinage petered out in the 560s, was Gotland, now more famous for hoards of Islamic silver coin but apparently starting early; but the previous one, up till about 480, was Öland. And everywhere else which was getting these coins, including another island focus, Bornholm in Denmark, which has lots too, was getting them from one then the other of those islands.

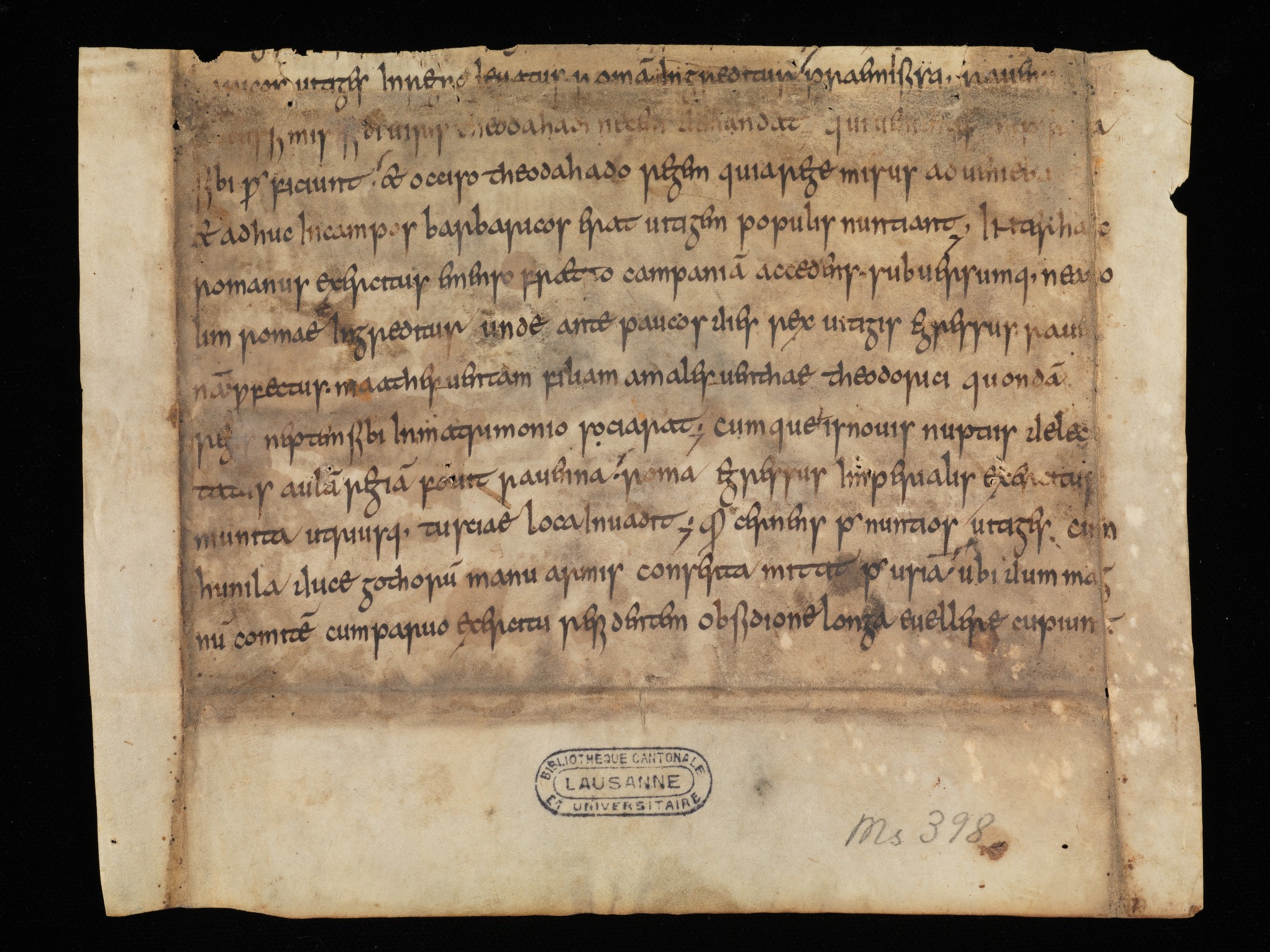

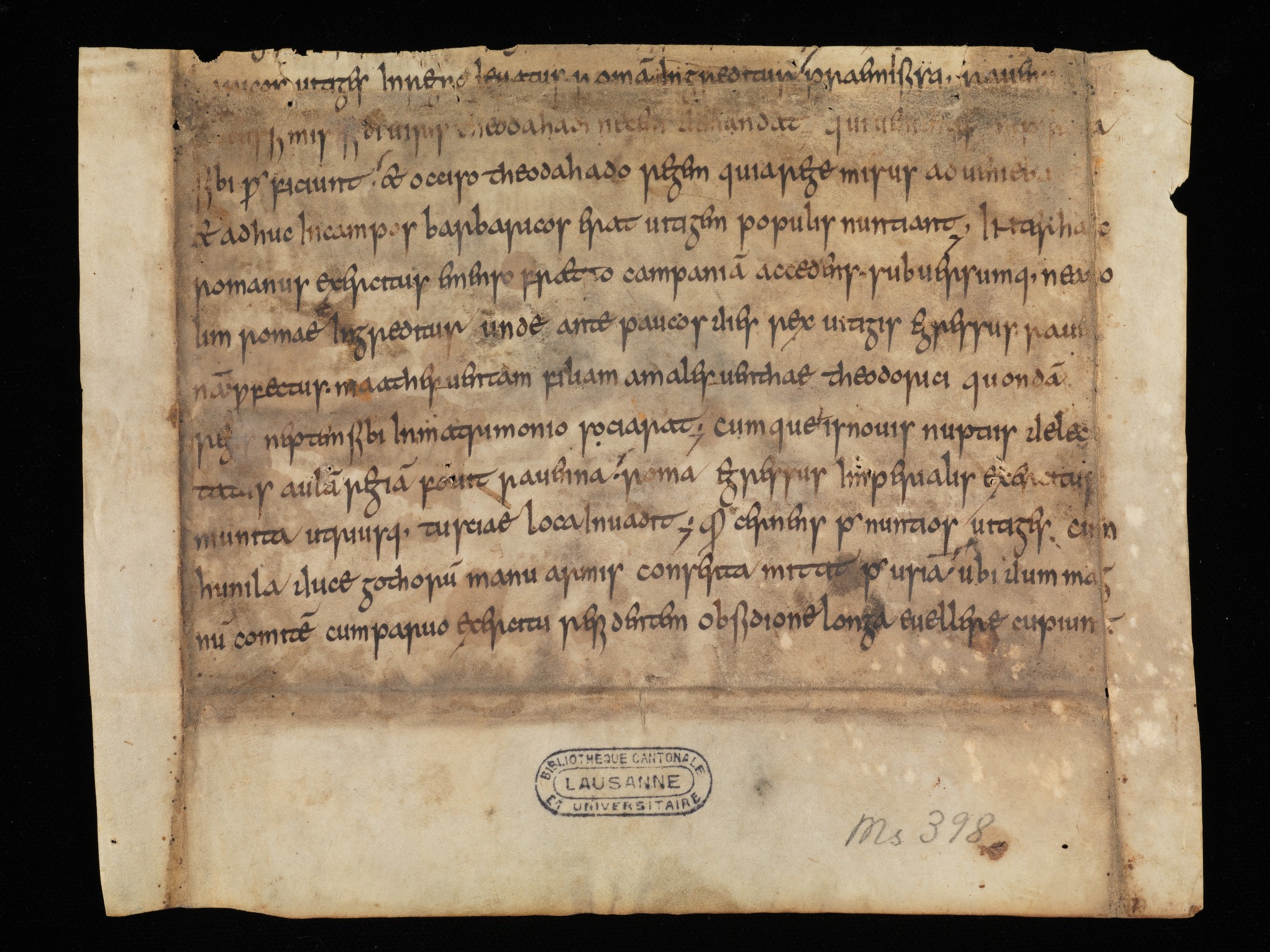

Now, there is a lot here, and it’s all known just from the coins, which may explain why I’ve seen so little use of this corpus in more conventional histories. The Ostrogoths were, at least in the sixth century, apparently prone to claiming ancestry in Scandinavia: Jordanes’s Getica, which he wrote around 550 in Constantinople alongside a history of the Romans in order to prove that the two peoples had equally honourable and ancient backgrounds, claims to have this from an earlier history by Cassiodorus which no-one but him seems ever to have seen, and he only for three days; but it doesn’t matter where he had the idea from, it was there to be had.8 Now, these coins obviously don’t prove anything about a deep Gothic prehistory in Sweden; but they do show pretty sharply that there was by the sixth century a strong connection between the political entity of ‘Ostrogoth’ and the place that was by then being claimed as their homeland. And we really don’t know what that connection was, just that it was worth a lot of gold. Military service is a possible, even a likely answer to that question, but only a hypothesis even so.

One of the oldest (fragmentary) texts of Jordanes, Lausanne, Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, Ms 398, fo. 1r, which was probably written at Fulda around 830, itself raising questions I can’t look at here; licensed under CC BY-NC via e-Codices, linked through and here

Secondly, the other end of the connection must have been something quite specific, or perhaps someone quite specific, because apparently the peoples of these islands were the Ostrogoths’ sole agents in the area, and that must have put them in quite a powerful position, since apparently everyone else was having to come to them for this imperial gold coin which was getting everywhere around southern Scandinavia, but getting there only from Öland and then Gotland. There’s a power structure there about which we just know almost nothing, but which is required to explain the coin finds.

Now, there is one more part of this context I’ve not yet mentioned, which is that Sandby borg is not alone in its sudden destruction. In fact, pretty much every coastal fortification of this early period in either Öland or Gotland which has been investigated met a messy end, and even when Fagerlie wrote it was recognised, largely because of the coin find threshold indeed, that this must have happened in the late fifth century in Öland and in the middle-to-late-sixth for Gotland, presumably in some associated fashion each time. The latter of these waves of destruction has been tentatively explained, when at all, in terms of the takeover of the people from whom Sweden takes its name, the Svear, chasing out the Gotlanders from a previously dominant position in eastern Scandinavia, and one could therefore guess at the former wave being how the Gotlanders got that position in the first place, apparently at the expense of the Ölanders.9 In both cases, while I might not now want to endorse these pseudo-legendary peoples’ existence, it’s tempting to see that stranglehold the populations of the two islands apparently had on imperial prestige goods as being too much for their power-hungry dependents to stomach, and episodes like Sandby borg the messy and unpleasant result.

The investigation under way at Sandby Borg, again from their Facebook site

So at this point, had we learned anything from the Sandby borg dig? If I’d already done my reading when I did that excited piece-to-camera in summer 2019 in the dark of the Barber’s coin room, would I have been saying confidently that this happened all the time, wasn’t unusual, in fact wasn’t even the only such coin find in Sandby or the most important one even if the actual borg hadn’t been found before, and that it told us nothing new? I don’t think so, because firstly, in terms of coin finds the finds here seem to say something different from the hoards; they were both early, separate and one’s an imitation. If Fagerlie was right then they should have arrived here maybe forty years after they were struck; and maybe they did, but I wonder if what we see here is actually the type of place these coins were going all over Scandinavia, perhaps heirlooms from service with a foreign army that it was worth having because it marked you as member of a kind of élite; and if I’m being properly fanciful, maybe the reason they stayed here was because for some reason Sandby borg’s defence included two very old soldiers who, in the end, lost their last battle, but whose status was recognised in death in so far as they got to keep their coin-badges. There have been hoards of Fagerlie’s types found nearby; but these two didn’t get hoarded, they stayed with their owners, and that might be important.

And then secondly, of course, there’s the macabre picture of how one of these settlements, apparently a casualty in a much bigger war, was not just destroyed but almost ritually ended, bodies across thresholds, buildings literally closed by the dead, and everything left where it had fallen, forever, never again to be visited. Or at least that was the plan, it seems. And that’s telling us about something more than a commercial power-grab; it’s telling us something about what that power meant and how it was explained, and if some day we figure that out properly, this site will be part of the explanation. But until then, it may remain at least mostly mystery, even though we apparently know more than many people think about the times in which the mystery was set.

1. The academic publication of these finds, until the full report at least, is Clara Alfsdotter, Ludvig Papmehl-Dufay & Helena Victor, “A Moment Frozen in Time: evidence of a late fifth-century massacre at Sandby borg” in Antiquity Vol. 92 no. 362 (London 2018), pp. 421–436, DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2018.21.

2. Andrew Curry, “Öland, Sweden. Spring, A.D. 480” in Archaeology (Boston MA March/April 2016), online here; “The Sandby borg massacre: Life and death in a 5th-century ringfort” in Current World Archaeology (London 25th July 2019), online here.

3. For the data see Arkadiusz Dymowski, “Roman Imperial Hoards of Denarii from the European Barbaricum” in Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology Vol. 7 Supplement 1 (Bucharest 2020), pp. 193–243; for some interpretation see Svante Fischer and Fernando López Sánchez, “Subsidies for the Roman West? The flow of Constantinopolitan solidi to the Western Empire and Barbaricum” in Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome Vol. 9 (Rome 2016), pp. 249–269.

4. See n. 5 below.

5. Joan M. Fagerlie, Late Roman and Byzantine Solidi Found in Sweden and Denmark, Numismatic Notes and Monographs 157 (New York City NY 1967).

6. Those that know me may be wanting at this point to suggest that the hippy is not in fact inner, and I who am currently sitting in a stripy woollen jumper that would fit in fine on the pampas and listening to Os Mutantes’s debut album would, I admit, have few arguments against that position. But it is pretty heavy, all the same.

7. See Cécile Morrisson, “Byzantine Coins in Early Medieval Britain: a Byzantinist’s assessment” in Rory Naismith, Elina Screen and Martin Allen (edd.), Early Medieval Monetary History: studies in memory of Mark Blackburn (London 2014), pp. 207–242.

8. If you want to read it, the oldest translation is helpfully online, as Jordanes, “The Origin and Deeds of the Goths”, transl. Charles Christopher Mierow in Texts for Ancient History Courses, 22nd April 1997, online here; for (competing) study of him and his project, try Lieve van Hoof and Peter van Nuffelen, “The Historiography of Crisis: Jordanes, Cassiodorus and Justinian in mid-sixth-century Constantinople” in Journal of Roman Studies Vol. 107 (London 2017), pp. 275–300, DOI: 10.1017/S0075435817000284 or Robert Kasperski, “Jordanes versus Procopius of Caesarea: Considerations Concerning a Certain Historiographic Debate on How to Solve ‘the Problem of the Goths'” in Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies Vol. 49 (Berkeley CA 2018), pp. 1–23, DOI: 10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.116872. For the kind of work which you’d think would love this stuff, but doesn’t use it, see Herwig Wolfram, “Origo et religio: Ethnic traditions and literature in early medieval texts” in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 3 (Oxford 1994), pp. 19–38, reprinted in Thomas F. X. Noble (ed.), From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms, Rewriting Histories 22 (London 2006), pp. 70–90; but against it, see Walter Goffart, “Does the Distant Past Impinge on the Invasion Age Germans?” in Andrew Gillett (ed.), On Barbarian Identity: critical approaches to ethnicity in the early Middle Ages (Turnhout 2002), pp. 21–37, also reprinted Noble, From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms, pp. 91–109.

9. For the wider background see Bjørn Myhre, “The Iron Age” in Knut Helle (ed.), The Cambridge History of Scandinavia, volume I: Prehistory to 1250 (Cambridge 2003), pp. 60–93; the end of the Gotland system is passed through on p. 84, but for specifics I had to go back to Alfsdotter, Papmehl-Dufay & Victor, “A Moment Frozen in Time”.

53.857629

-1.924299