I owe apologies for sporadic blogging again; it’s been a difficult couple of weeks, is all I can say, and also that forthcoming posts need photographs I haven’t yet processed. But we’re getting there, and to start with here’s the post I realised that I hadn’t written in the last post, announcing my almost-most-recent publication. This is one of those insider stories, kind of. You may remember I gave a paper in China looking at the Emperor Anastasius’s reform of the Roman-or-Byzantine base-metal coinage and suggesting that it was not in fact a popular move at the time? If, for some reason, you’ve actually read that, which bearing in mind that the official version is in Chinese with English footnotes might, I grant you, be difficult—there is an English text online here—you’ll know that there’s a kind of throwaway section near the end suggesting that the reform coins of 40-nummi which we usually call folles probably weren’t called that at the time.1

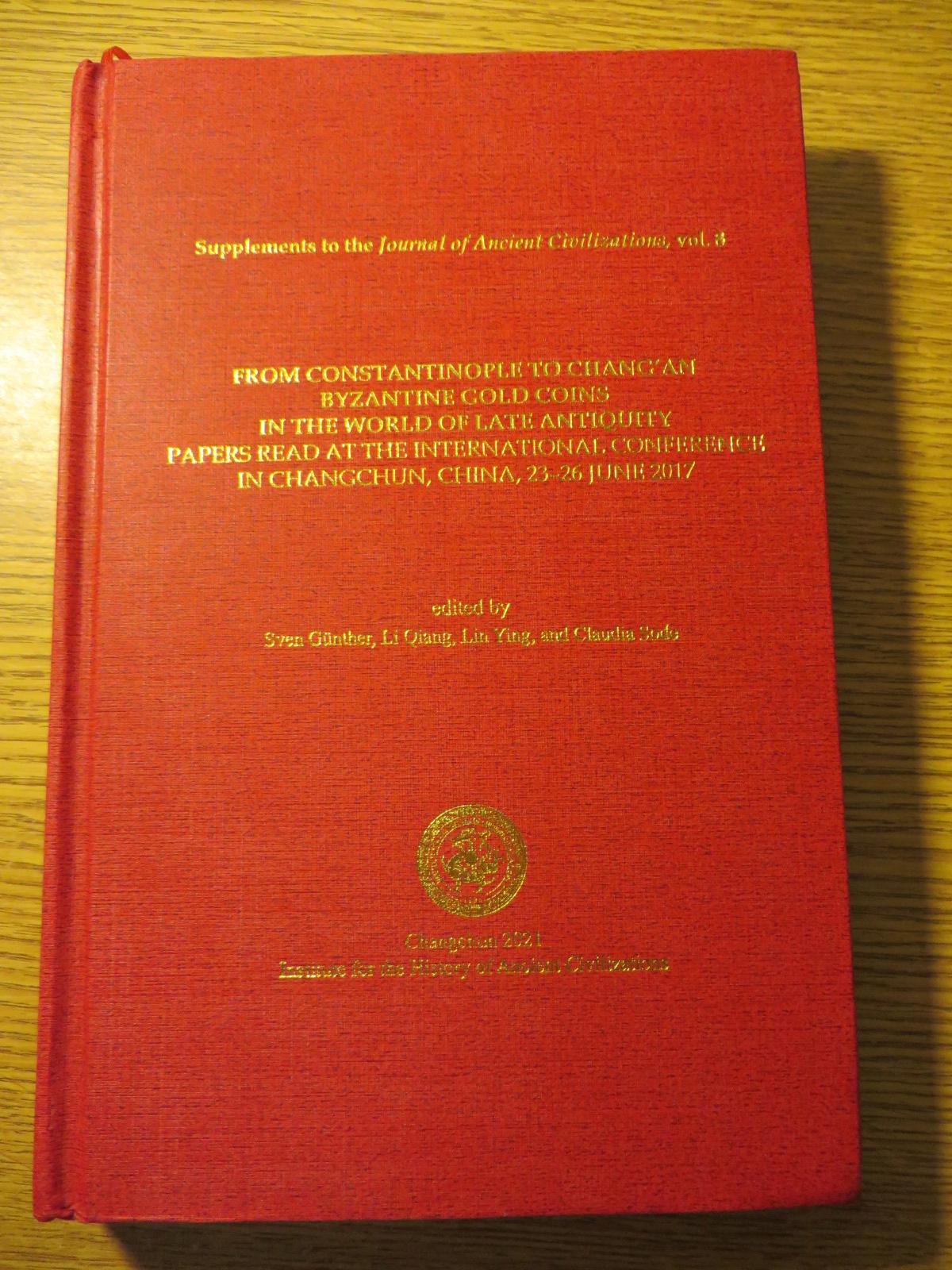

Copper-alloy 40-nummi coin of Emperor Anastasius I struck at Constantinople in 498-512, Birmingham, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, B0036

So that was as far as I had intended to take that. Every time I write something numismatic I think it will be the last thing, and then someone asks me for another paper and I can’t refuse them for some reason. This time the reason was that there was being constructed a volume of articles in honour of Miquel Crusafont i Sabater, one of the most important numismatists in Catalonia and someone whose work I helped see into English back when I worked at the Fitzwilliam Museum.2 After presenting that work in Catalonia, I met Jaume Boada, who nowadays edits the journal of the Societat Catalana d’Estudis Numismàtics, Acta Numismàtica, which En Miquel started and was therefore the best place to publish essays in his honour, and Jaume very kindly thought I should be in it. That happened in mid-2021, and I thought that he was right and I should. But the only thing I even possibly had was the idea that folles weren’t called folles.

Cover of Acta Numismàtica Vol. 52, Homenatge al Dr. Miquel Crusafont (Barcelona 2022),

For some reason I was worried this wouldn’t make much of an article. By the time I’d worked it up, however, it had become almost 9,000 words, with a table and stuff, and had meant not just quite a lot of reading of really bad metrology (A. H. M. Jones was indubitably a brilliant historian – but never ever trust his sums!3) but also doing that thing that we can now do to perform an end-run on almost all older scholarship, that is, electronic search of digital corpora, which led me into having to handle both Greek and papyri, sometimes together, neither of which are things in which I have any real training. If this all worked out, it’s only because of the work of Roger Bagnall and because of two incomparable databases, Papyri.info and the Perseus Digital Library Word Study Tool, which have allowed me to mobilise the brains of others to patch what I don’t know in a way that scholars of twenty years ago just couldn’t have done.4 Even so I’ve already found one mistake, which I can only hope doesn’t get perpetuated, and rested part of my argument on an old article by Michael Hendy which I have subsequently learned is now considered not to be right, a rare thing for Hendy.5 But for all that, I think I might still be right, overall. So what does it say?

First page of Jonathan Jarrett, "Follis or follaron? The name of the Byzantine coin of 40 nummi" in Acta numismàtica Vol. 52 (Barcelona 2022), pp. 225–248

Well, here’s the abstract I sent in:

The standard term for a Byzantine base-metal coin is follis, but this word is older than the coins that numismatists so name, meaning especially a bagged amount of currency, a usage which overlapped with the coins. This article shows that when the first such coins were introduced, in the reform of Anastasius I in 498 CE, contemporaries in fact called them follares, not folleis. The article sets out the evidence for this, and disarms apparent evidence for the term follis as meaning coins. It concludes that numismatists and curators should probably abandon the term follis for coins before at least the reign of Justin II (565-85 CE).

World-changing? Perhaps not. But the people it was meant for liked it and that’s what counts. Of course, none of them are normally concerned with Byzantine coinage, and in that respect this was an odd place to put the article.6 But I wouldn’t have written it if these people hadn’t asked! So maybe by mentioning it here I can start getting the word out more widely. I haven’t actually put it online, which I realise doesn’t help, but for those that need it I can probably find a file to send you…

1. 加莱特乔纳森, ‘拜占庭帝国的市场交易与阿纳斯塔修斯一世的货币改革’, transl. 张 月, in 王春法 (ed.), 货币与王朝: 国际视野下钱币的影响与改变 (北京 2021), pp. 266–276 at pp. 275-276.

2. Miquel Crusafont, Anna M. Balaguer and Philip Grierson, Medieval European Coinage, with a catalogue of the coins in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 6: The Iberian Peninsula (Cambridge 2013).

3. And specifically the sums in A. H. M. Jones, “The Origin and Early History of the Follis” in Journal of Roman Studies Vol. 49 (London 1959), pp. 34–38, where for example over pp. 36-38 he had to found a sum on the premise that pork prices in Rome were the same in 363 and 452 (p. 36) despite the fact that he admitted massive inflation over the period (p. 37) and documented prices twice as high in Egypt in between (p. 38), and I’m afraid it’s almost all like that.

4. The Bagnall work specifically Roger S. Bagnall, Currency and Inflation in Fourth Century Egypt, Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists Supplement 5 (Chico CA 1985), found online here, a really helpful little book.

5. That being Michael F. Hendy, “On the Administrative Basis of the Byzantine Coinage c. 400-c. 900 and the Reforms of Heraclius” in University of Birmingham Historical Journal Vol. 12 (Birmingham 1970), pp. 129–154, which I now find overthrown by work such as Andrei Gandila, “Free Market, Black Market or No Market? Money and Annona in the Northeastern Balkans (Sixth to Seventh Century)” in Journal of Late Antiquity Vol. 14 (Baltimore MD 2021), pp. 294–334, not someone I carelessly gainsay! Neither was Hendy, of course, but as we have seen even Homer could nod.

6. Citation for you: Jonathan Jarrett, “Follis or follaron? The name of the Byzantine coin of 40 nummi” in Acta numismàtica Vol. 52 (Barcelona 2022), pp. 225–248.