Not right now, I admit; right now I am doggedly trying to clear any research time at all between the marking, lecture preparation, training and rewriting a long-running module of my predecessor’s to cope with the kind of limits of digitisation I was writing about here the other day, and when I get that time there’s a review, an article and a final version of a conference paper that need sending off first, but nonetheless, since November last year I have been contracted to produce my next monograph and it’s about time I mentioned it here. It will (probably) be called Managing Change: Borrell II of Barcelona (945-993) and his times and I’m due to send the final manuscript to Palgrave MacMillan at the end of June 2016. I thought I should say something about why I think it’s worth writing, how I got it to contract stage and what will be in it, so here goes.

Count-Marquis Borrell II of Barcelona, Girona, Osona (945-993) and Urgell (947-993), as pictured in the Rotlle genealògic del Monestir de Poblet, c. 1400 (from Wikimedia Commons)

At one level this book is getting written because of professional necessity, but at another one it’s because its seeds have been kicking round my head for years, the unwritten extension of one of the chapters of my doctoral thesis.1 You all know I have many thoughts about Count-Marquis Borrell II of Barcelona (and also Girona, Osona and Urgell). At the latter stages of my write-up process I was as far down my rabbit hole as to occasionally imagine a small avatar of him in my head shouting ineffectually at me to get on with it. I’ve been wanting to get this written ever since then but other things have kept seeming like more immediately useful ideas. Then, a few months after I’d started making a decent attempt to bring the blog up to date by blogging every morning, as I have described before:

“then Christmas happened and in that time someone heard me saying that if I was going to get another job after this one I probably needed to heed one academic’s advice and get myself a second book. That someone pointed out that I had been going on about the one I’d write for ages, and would probably be both happier and more successful if I actually got on with it, and they were right, of course, but really the only time I could free up for that was the time I was using for blogging.”

So with that grimly accepted there arose the question of what to write. I envisaged, and still envisage, this book as a semi-biographical study, because there is basically almost nothing written specifically about Borrell even in Catalan, so it seemed important to get the basics down, but then there would be thematic chapters picking up on the various aspects of his rule I think make interesting points of comparison.2 It seemed clear that I should start with the biographical part, to get that in order and also to demonstrate to a reader that there was a story here that could be told, but that meant getting the evidence into a state of arrangement I’d never yet managed. I have a database with all Borrell’s charters atomised in it, but there’s more that could be done, and once I’d done it I was surprised how much narrative evidence also had to be slotted in, either from Richer of Reims or from Arabic sources and all very bitty but still more than I’d realised and quite informative, to which one could add Gerbert’s letters and so on. I arranged all these into a conspectus of datable or near-datable nuggets of information, and by the end of it there were 218 different incidents of Borrell’s career on record, much more than we have for most tenth- or eleventh-century persons even at élite level.

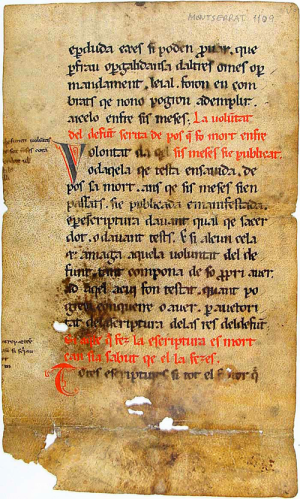

Archivo de la Corona d’Aragón, Cancilleria, Pergamins Seniofredo 39 (reduced-quality version), with Borrell’s alleged signature lower centre

Moreover, the very effort of getting them in order made coincidences and significances apparent that I’d never noticed before; two or three things happening in Manresa suddenly at the same time, an absence of appearance in Osona until much later than I’d realised, a gap in the evidence for Girona that I’d already noticed and tentatively blamed on Count-Bishop Miró Bonfill of Besalú and Girona actually being more endemic, and so on. I think the most obvious of these was that Borrell got married in the immediate aftermath of his brother, Miró III Count-Marquis of Barcelona (they shared) dying in 966, even though he was probably thirty-five already by then (and there’s no sign that Miró was married either). I’m still puzzling over that lack of attention to the succession, but in any case, it’s clear that plans then changed. So that sort of thing emerged from the close attention to chronology and made this feel a lot like research.

But the biography can be written, so I wrote it, and then after also spending some time making a list of all Borrell’s relatives documentable alive during his lifetime because keeping them straight in my head was proving impossible—and there’s sixty-four of them, which is also a fairly unusual source-base I think, though I doubt he knew even half of them himself—I also had stubs of three other chapters, one of which, on the conceptualisation of comital power, I dressed up for presentation and tentatively sent off to Palgrave with the biographical chapter, the conspectus and a proper actual proposal. I find it hard to say why I decided so quickly on Palgrave: they make nice-looking books, they shift copies and I want this book to make some sales, their academic standards are high enough to be credible, they don’t have the ugly copyright agreements of some companies, but one could say the same of other publishers. So far it has been a good choice, though; they acknowledged, sent out for review very quickly and the reviewer’s comments were, well… it would be fair to say that the reviewer saw in my proposal the potential for a whole other book, one which I’d like to write but it would take me years. I may yet, but I managed to convince Palgrave that with enough deliberate comparison built in, this book would do as a necessary stepping stone to the great new synthetic history of power and government in tenth-century Europe.3

I actually do think, though, that if such a book is to be written—and I think we need one, I do think the tenth century is a crucial period of formation in the mess of post-Roman Europe, in which the dust from the Carolingians’ attempt to renew Rome one last time settles in definitive ways that are hugely diverse because of the chaotic state of post-imperial disunification, and that if we can understand the tenth century better we will understand everything that follows from it better as a result—Borrell’s reign is an excellent place to start. Consider: he lived at the very end of the Carolingian rule of which he was the notional servant, and which he initially tried his best to ignore without actually disclaiming it.4 Big things were afoot; the Carolingians were finishing, the Ottonians were running into trouble, the Caliphate of al-Andalus was entering its dangerous red giant phase whose early end no-one could have foreseen, elsewhere in Europe the Vikings were back; everywhere or almost everywhere structures of government, finance, and even religion were in flux and proving unequal to the strains of the times. He was, indeed, caught up in and possibly held back the governmental privatisation process that we sometimes call the ‘feudal transformation’. All these things worked out different in Catalonia because of what Borrell did, the not-so-great man (because I don’t necessarily see him as a success) atop the big waves of historical change trying as best he could to make sure he and his family and (to a lesser degree, but a real one) his people came out of the curve more or less as they’d started or better. And we have more than two hundred documents of him busy at these things. Of course, as I admit up front in the book, that is to say that we know what he was doing on some of less than one half percent of the days he was alive, but that’s still surprisingly much for the tenth century. Something can be done here, and I’m now contracted to do it.

Not a perfect map—is there such a thing?—but it makes the point: things with names we still have are on this map but they are not yet what and where we expect them

So at the moment, this is the way the chapter plan looks.

- Preface and Introduction

- Biography

- Ancestry, Rivals and Descendants

- The Opening World

- Money and the Economy

- Managing Manpower

- Piety and Patronage

- Administration and Reform

- Theories of Rule

- Conclusion

Why the book needs to be written, the lack of a decent study of him and the outdated mistakes about his rule that still circulate, the above justification and how I’m proceeding

A chronological narrative of his life and career marking its big changes

His family and the ways in which they impinged on his life

His contacts abroad in an era when Catalonia was freshly expanding them5

Covering the fisc and the currency reform for which I’ve argued6

Reprising my doctoral work here slightly, the ways in which Borrell deployed patronage and upon whom

A prince over the Church or a pawn of his bishops? A little from column A, a little from column B…

Principally with respect to the law and judges, since that’s what we can see, but also land management

How the counts and others who held power here thought of that and how it was expressed

I think I’ll have a better idea what this will be once I’ve written the rest!

I’m happy to talk about it more in comments, and equally happy in a strange kind of way to be nagged to get on with it; I’d like to be sure there’s an audience, after all. It will get done either way, though, and some day you’ll be able to buy it. Whether it’ll still look like this then, only the next year or so will tell, however!

1. Jonathan Jarrett, ‘Pathways of Power in late-Carolingian Catalonia’, unpublished doctoral thesis (University of London 2005), pp. 221-253, rev. as J. Jarrett, Rulers and Ruled in Frontier Catalonia 880-1010: pathways of power (Woodbridge 2010), pp. 141-166.

2. The basic reference is still Prosper de Bofarull, Los Condes de Barcelona vindicados, y cronología y genealogía de los Reyes de España considerados como soberianos independientes de su Marca (Barcelona 1836, repr. 1990), 2 vols, I, online here, last modified 23 July 2008 as of 14 January 2015, pp. 64-81; to it, as far as I know, the only specific studies of Borrell that can be added are Miquel Coll i Alentorn, “Dos comtes de Barcelona germans, Miró i Borrell” in Marie Grau & Olivier Poisson (edd.), Études Roussillonnaises offertes à Pierre Ponsich : Mélanges d’archéologie, d’histoire et d’histoire de l’art du Roussillon et de la Cerdagne (Perpignan 1987), pp. 145-162; Cebrià Baraut, “La data i el lloc de la mort del comte Borrell II de Barcelona-Urgell” in Urgellia Vol. 10 (Montserrat 1990), pp. 469-472; and Michel Zimmermann, “Hugues Capet et Borrell: Á propos de l’«indépendance» de la Catalogne” in Xavier Barral i Altet, Dominique Iogna-Prat, Anscari M. Mundó, Josep María Salrach & Zimmermann (edd.), Catalunya i França Meridional al’Entorn de l’Any Mil: la Catalogne et la France méridionale autour de l’an mil. Colloque International D. N. R. S. [sic]/Generalitat de Catalunya «Hugues Capet 987-1987. La France de l’An Mil», Barcelona 2 – 5 juliol 1987, Actes de Congresos 2 (Barcelona 1991), pp. 59-64, which is not a whole lot of pages despite the length of the footnote.

3. I don’t know who this reviewer was but I have an idea. If they know who they were, and happen to be reading, once this is out I want to talk to you about the next one sir or madam…

4. See J. Jarrett, “Caliph, King or Grandfather: strategies of legitimization on the Spanish March in the reign of Lothar III” in The Mediaeval Journal Vol. 1.2 (Turnhout 2012 for 2011), pp. 1-22.

5. Here still basically following Ramon d’Abadal i de Vinyals, Com Catalunya s’obrí al món mil anys enrera, Episodis de l’història 3 (Barcelona 1960, repr. 1987).

6. See J. Jarrett, “Currency change in pre-millennial Catalonia: coinage, counts and economics” in Numismatic Chronicle Vol. 169 (London 2010 for 2009), pp. 217-243.