Would you like another source to ponder? Oh good. I have, in the course of my teaching at the University of Leeds, done quite a lot of scratch translation of sources here and there, as have I here of course; but at Leeds I run a Special Subject, an archaic but effective Cambridge pattern of module which involves deep immersion in the primary evidence for a subject, and my students, of course, don’t have Latin, or Arabic, of if by some chance they do they don’t have the medieval versions of either. They don’t usually have any European languages other than English either, and everything crucial to the teaching has to be accessible to everyone, so no translations that aren’t in English can help. One way or another, I’ve piled up a lot, but still the time often comes, especially when dissertations loom, that a student finds something else that would be really handy if they could read it… And sometimes, if it’s short, I’m able to help. And that’s how in February 2021 I found myself in the back of volume II of the Catalunya Carolíngia translating the Capitulary of the Synod of Attigny, a meeting in 874 whose record describes…1 Well, I’ve written about it before here, but never given it in full, so I thought I would let you read and see and I saw one new point I could get out of it to make it worth your while. The post title mainly refers to the third heading, but it’s all interesting as an example of early medieval religious government.

In the Year of the Incarnation of the Lord 874, the lord King Charles issued these capitula, which follow, at Attigny on the Kalends of July.

- The bishop of Barcelona pleads that Tirs, priest of Córdoba, setting up a congregation around himself in a church between the walls of the selfsame city, is usurping almost two parts of the tithe of the selfsame city and, without any licence, presumes to celebrate masses and baptism in the selfsame city, and extends communion to those who are summoned by the bishop to the mother church even for the solemnities of Easter and the Nativity of the Lord and, despising the bishop, renounce him. Whereof the sacred Council of Nicæa says:

"Whatever priests or deacons, or any others enrolled among the clergy, recklessly and dangerously and not having the fear of God before their eyes or regarding the rule of the Churches, shall separate from the Church, these ought not by any means to be received in another church, but every constraint should be imposed upon them so that they return to their own parishes. If they do not so, it is necessary to deprive them of communion."

This is decreed of Tirs, who has irregularly separated from his own city. Further of him and of other contemptibles the Council of Antioch says:

"If any priest or deacon, despising his own bishop, sequester himself from his Church and, gathering people around him, set up an altar and should neither acquire episcopal consent nor wish to consent to or obey the bishop though summoned to once and again, let this man be damned in every way, and let him find no other remedy, since he is not fit to receive the dignity. If he persist in disturbing and soliciting the Church, let him be suppressed like a rebel by external powers."

This the canons of the African province also decree. But this chapter of the Antiochene council has established quite enough of a position. Of basilicas and tithes, moreover, the holy canons decree:

"That all basilicas, which have been built in various places or are daily being built, shall according to the first rule of the canons be in the power of their bishop, in whose territory they are located."

And the holy Gelasius in his decretals, says:

"From the renders and just as much from the offerings of the faithful, just as the authority of the Church proportionally deems, and just as is reasonably decreed, it is suitable to make four portions: of which one should be the bishop’s, another the clergy’s, another the poor’s, and the fourth applied to buildings. Of these, just as the priests shall receive the whole of the noted quantity for the ministry of the Church, thus the clergy may insolvently add nothing to their expenses beyond their assigned sum. That indeed which is attributed to the ecclesiastical buildings, let be truly assigned to this work for the aforementioned manifest installation of the places of the saints; since it is evil, if the sacred altars lie destitute, for the chief-priest to convert this designated income into his own wealth. Let the selfsame portion assigned to the poor, by whatever divine means may be shown, have been dispensed, however, no less according to what is written: ‘so that they may see your good works and glorify your Father, who is in Heaven, it must be preached with present witness and the criers of good report not be silent.’"

And indeed these things about the renders and offerings of the faithful are specially decreed of those which belong to the bishops of the churches in those regions where resources are not abundant, but which subsist as much from the tithes of the faithful as from offerings. As for the other rural parishes, how much the bishops in the regions of Septimania and Galicia ought to exact from their priests is demonstrated by the second canon of the Council of Braga and the fourth of the Council of Toledo. Of those moreover who retain the priest Tirs in the church of the city of Barcelona against the authority and the will of the bishop of Barcelona, the capitulary of the Augusti lord Charles and lord Louis decree as follows:

"Of those, who without episcopal consent install priests in churches or eject them from them and do not care to be admonished by the bishop or by any missus Dominicus, that they shall suffer our bann, or endure some other punishment."

Since indeed it is lengthy to bring those persons to the presence of the king and dangerous to remove them further from the March, the lord king will command his marquis that he should distrain and punish them. About the tithes indeed, which ought to be in the power and disposition of the bishop, which they have stolen from the mother church and by their pleasure give to another, the same capitulary says:

"Whoever shall steal the tithe from a church to which it ought justly to be given, and presumptuously or on account of gifts or friendship or whatever other reason shall have given it to another church, let him be distrained by the count or by our missus so that he restore the same quantity of tithe as is required by law."

And also:

"Of those who have already neglected for many years to give ninths and tithes, either in part or in whole, we wish that they be constrained by our missi so that they answer according to the previous capitulum for the ninth and tithe of each year according to the law and also for our bann; and let this be made clear to them, that whoever should repeat this negligence, in which they ought to pay these ninths and tithes, let him know that he will lose his benefice."

- About this, which [the bishop] pleads, that through the insolence of the priest, by his ministry [the bishop’s] castle of Terrassa has been subjected to the power of the faction of Baio, the ruling of the aforesaid Council of Antioch is to be followed in the case of the insolence of a priest. Against the faction of Baio, moreover, is to be followed the canon of the council of Carthage, which says:

"It is seen everywhere that defenders have been demanded by the emperors, on account of the affliction of the poor, by whose sufferings the Church is fatigued without intermission, so that the defenders may be delegated to them by the provision of the bishops against the powers of the wealthy."

The above-placed capitulum from the capitulary of the Augusti is also to be followed:

"Of those, who without episcopal consent install priests in churches or eject them from them."

- As for this, which [the bishop] pleads, that a certain Goth, Madeix, has by fraud and cunning has obtained by precept the noble and ancient church of Saint Stephen, where with the worship of God put aside the base conversation of rustics now occurs, and similarly the Goth Requesèn has by fraud and cunning obtained the field of Saint Eulalie by precept, let the royal order command these things to be diligently and truthfully investigated by our faithful missi, and let the selfsame inquest be made to be brought to our notice under seal through the guard of faithful men. And if it be found that the aforesaid church of Saint Stephen and the field of Saint Eulalie were obtained by the aforesaid Goths through precepts, let the selfsame precept be sealed according to the law and brought before the royal presence along with the selfsame inquest, for a public judgement of who there has been who has lied in their entreaties, so that what they have sought may not profit them and they may lose the selfsame benefice there in the documents which was transferred by the rescripts, and the Church of Barcelona may receive by royal magnificence that which is its own.

Lots of things to notice here, but let’s start with the fact that though this document is printed as a capitulary of the synod, I would say that it’s vanishingly unlikely that the sole business of a major synod of Charles the Bald’s kingdom was complaints raised by the bishop of Barcelona (who, by the way, though not named here, was probably at this time the mysterious Frodoí of whom we have talked here before). This is pretty obviously just the record which the bishop of Barcelona took home with him of the bits which mattered to him (although going further than that is hard, because the text is only known from a printing of 1623 that didn’t name its source). The issue of what counts or doesn’t as a capitulary or as Carolingian law is raised good and high by this text.2

Next, we see that whoever they were the bishop of Barcelona’s status was much challenged at this time! But lots of the challenges have back-stories that this document isn’t interested in discussing. Who Tirs was we have no idea, though it’s interesting that he came from Córdoba at a point when Charles the Bald was also interested in acquiring relics of the fairly recent and much-disputed Christian martyrs of that city; channels were maybe more open than usual to clergy moving zones at this point.3 But still: to waltz in and appropriate more than half of a city’s tithes, presumably by the will of its congregation? That suggests bigger things than charismatic authority; that suggests major problems with the standing of the actual bishop, perhaps even a disputed election. This document has thus been part of the case that Frodoí, who it may or may not have been complaining to the king here, was the king’s outsider candidate pursuing an unpopular agenda, perhaps the replacement of the local Mozarabic liturgy with the Carolingian-preferred Roman one, and meeting opposition, which, in the full version of this thesis, he would then try and master by "luckily" finding the relics of Saint Eulalie in Santa Maria del Mar, thus proving his divine backing.4 Well, maybe. But the apparent link between Tirs and Baio suggests a further dimension.

Panoramic view of the three churches of Egara at Terrassa, “Egara. Conjunt episcopal” by Oliver-Bonjoch – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons.

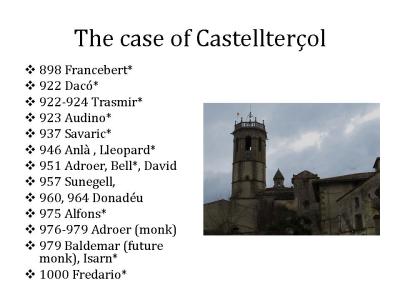

The key element here is Terrassa. The three palaeochristian churches of Terrassa, though very close to Barcelona, had under the Visigothic kings been the site of their own bishopric. That seems to have been inactive by the time of the Carolingian conquest, so the Carolingians combined its territory into Barcelona.5 That Tirs was in a position to put someone in Terrassa who could then keep the Carolingian bishop of Barcelona out has always suggested, to me, that what Tirs was actually doing was attempting a revival of the bishopric of Terrassa. At which rate, the "two thirds" of the bishopric the Carolingian bishop was complaining about losing to him might just be the old see, freshly split back off at least for now. All this wouldn’t necessarily make Tirs and Baio honest actors; but it does mean that they, too, could probably have found Church council legislation in support of what they had done.

Then on that subject, aren’t the sources of authority in play interesting? We have an ecumenical council (I Nicæa), provincial ones from Asia (I Antioch) Africa (IV Carthage), Gaul (I Orléans) and Hispania (IV Braga and VII Toledo), as if all were now in the inheritance that the Carolingian Church could draw on – but also, had they been there to plead their case, lending legitimacy to the Visigothic Church arrangements which Tirs and Baio may have been trying to revive – and then a Carolingian capitulary, cited as law whether or not this capitulary in which we have the cite counts as law. But it’s also misattributed: it’s the one we call the Capitulary of Worms, and it wasn’t issued by Charles and Louis, i. e. Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, Charles the Bald’s daddy and granddad, but by Louis the Pious and Lothar I, i. e. daddy and Charles’s sometimes-wicked half-brother.6 Charles was 1 at the time, so you could see why he might not remember; but were the available texts bad, was the memory of Lothar and the year 830 awkward, or was it just that Lothar I didn’t clearly have authority over the March so that it seemed better to attribute the ruling to the two kings who conquered it? But to me it’s also the idea that here secular law and Church law are equivalently valid, and as if to match that, not only was the bishop of Barcelona clearly hoping for the king, not the synod, to sort the matter out, but one of the synodal judgements cited, I Antioch 5, even requires "external authority" to get involved. So here we have a Church and a state which do recognise each other as external to themselves, but still assume the other’s unquestioning support.

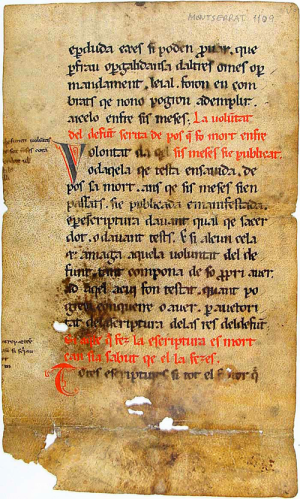

This isn’t the right charter – it won’t surprise you, perhaps, to know that Madeix and Requesèn’s charters don’t survive7 – but it gives you some idea of what these things usually look like as we have them. It is a 12th-century copy of a precept of Charles the Bald for the monastery of Sant Medir, now in the Arxiu Comarcal de la Selva

But then there’s cap. 3, which is no-one’s problem but the king’s. There’s no canon law to cite here, no Church councils that bear on the issue, because the only authority in question is Charles’s, through these precepts that the two Goths Madeix and Requesèn may have got from him. Here, of course, Charles was in a difficult position. In the early years of his reign he had handed out concessions of land to willing followers as only a man embroiled in a civil war of uncertain outcome with no other reliable access to information about the areas in question might – “I own that? Sure, have it, not like I’m seeing anything from it. How many troops did you bring again?” – but, although there is disagreement about this, I have argued elsewhere that pretty soon Charles had switched his policy with such Hispani begging land grants to handing over his rights and therefore their immunity from certain dues and duties to the local Church.8 At least, in most areas, but not, apparently, in Barcelona proper, where there seems to have been enough of a core group of people who could still be called Goths that they were worth maintaining as some species of royal following. That policy had here come back to bite Charles: he had given grants to lands to which, perhaps because they had belonged to Terrassa, it was possible that the cathedral of Barcelona had a claim. Furthermore, although it’s not clear from this document, he had done this quite some time ago, because when his son ratified Barcelona’s possession of these lands in 878, it was explained that, “formerly a Goth by the name of Requesèn took these lands from the power of Bishop Joan and held them without right”.9 Bishop Joan is only attested up to 858, and Bishop Adaulf between then and Frodoí turning up in 862, so Frodoí had in this respect walked into a situation that was at least four years and two bishops old when he became bishop himself and was at least sixteen years old by the time he felt able to get the king to address it. This, along with the non-standard coinage Frodoí may also have issued, makes me think that he was not Charles’s chosen agent of reform in the area, but rather someone with a weak power base who was only able to cultivate the kings quite late on. It makes one wonder how long Tirs had been at Terrassa: was he in fact a fugitive from the martyr movement? No way to know, but…

In any case, in 874 this mostly worked. In principle, as we see from the rest of the document, Charles would back up his bishop to the fullest extent; but where it meant going back on his own word, however hasty, it was better to hold a local inquest, "for a public judgement of who there has been who has lied in their entreaties". Because one thing had to be for sure: the blame would lie on the March, either with the Goths or, alarmingly for him perhaps with two-thirds of his congregation currently voting differently, with the bishop. The one place blame was not going to lie was with the king who had issued the precepts!

It’s easy to say that the rulers of this era moved in a different world to our politicians, in which they were apart from anything else primarily responsible in the eyes of all to God, and to the actual people, if at all, only through some quite selective and not very powerful organisations of the social élite who relied on the king too much for position ever really to hamper him. It’s equally or more easy, I guess, to go the other way instead and just assume that these rulers were just like ours, with their eyes only on the immediate prize and any talk of God just a cynical way to smooth out opposition to their own will. It’s certainly possible to read this document in either direction, according to your preference: was Charles mobilising Church authority to keep his man in power? Maybe, at least up to the point where his man called Charles’s own authority into question! And I suppose that the alternative perspective, in which Charles was here the prisoner of Church demands until they came down simply to property, could be seen equally cynically by the fashionable device of seeing the Church as an organisation whose goals were primarily political and financial, with any actual religious motive invisible behind their peculation; this is, after all, roughly how we see our own politicians now so why should anyone claiming power be different?10 It’s possible, indeed probably preferable, to see the medieval Church as a massive state-endorsed charity whose holdings amounted to substantial policy influence but whose goals remained ultimately religious; but it might fairly be said that the bishop of Barcelona here did not "surface" that priority in this plea to the king.11 All the same, it seems clear to me that at the end of this rather difficult interaction, Frodoí (if it was he) may have got most of what he wanted but the real winner was still Charles the Bald, and that’s politicianning however you see it, I reckon.

1. You can find it in Ramon de Abadal i de Vinyals (ed.), Catalunya carolíngia volum II: Els diplomes carolingis a Catalunya, Memòries de la Secció històrico-arqueològica 2-3 (Barcelona 1926-1952), 2 vols, Ap. VII. Abadal helpfully identified all the conciliar and legal references it makes, which I’ve hyperlinked rather than footnote as that seems more directly useful.

2. Abadal gave as ultimate source (ibid. vol. II p. 430), “Sirmond, Capitula Caroli Cavli et successorum, Paris, 1623, que el tragué d’un còdex desconegut.” For the difficulties of the genre see these days Christina Pössel, "Authors and recipients of Carolingian capitularies, 779–829" in Richard Corradini, Rob Meens, Pössel and Philip Shaw (edd.), Texts and Identities in the Early Middle Ages, Forschungen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 12 (Wien 2006), pp. 253–274, or Shigeto Kikuchi, "Carolingian capitularies as texts: significance of texts in the goverment of the Frankish kingdom especially under Charlemagne" in Osamu Kano (ed.), Configuration du texte en histoire. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference Hermeneutic Study and Education of Textual Configuration, Global CEO Program International Conference Series 12 (Nagoya 2012), pp. 67–80, for my copy of which I must thank the author.

3. See, among other things, Ann Christys, "St-Germain des-Prés, St Vincent and the Martyrs of Cordoba" in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 7 (Oxford 1998), pp. 199–216, DOI: 10.1111/1468-0254.00025.

4. For this thesis, see Joan-F. Cabestany i Fort, "El culte de Santa Eulàlia a la Catedral de Barcelona (S. IX-X)" in Lambard: estudis d’art medieval Vol. 9 (Barcelona 1996), pp. 159–165, online here.

5. Manuel Riu, "L’església catalana al segle X" in Frederic Udina i Martorell (ed.), Symposium Internacional sobre els Orígens de Catalunya (segles VIII-XI) (Barcelona 1991), 2 vols, vol. I pp. 161–189, online here, pp. 161-164, is safe enough on this. For where it’s not, see Jonathan Jarrett, "Archbishop Ató of Osona: False Metropolitans on the Marca Hispanica" in Archiv für Diplomatik Vol. 56 (München 2010), pp. 1–42.

6. If the messy history of the Carolingian royal family at this point in history is new to you, the very short version would be: Charles was the youngest son, by a different mother, of Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious, ruler like his father of most Western Europe, who had enough trouble settling his succession arrangements to the satisfaction of his three adult sons by his first marriage already when Charles came along, and the result when Louis died in 840 was three years of war and thirty years of mistrust and occasional coup attempts thereafter. The longer version is best got through Janet Nelson, Charles the Bald (London 1992).

7. Though this didn’t stop Abadal indexing them as documents we know once existed, as Catalunya Carolíngia II Particulars XXII & XXIII. He dated them to before 858, for reasons we’ll go on to discuss, but they would probably fit best of all among the many documents Charles issued for Catalonia in 844, for which see n. 8 below.

8. As just said above, Charles’s maximum generosity to Catalonia was while he was besieging his ertswhile marquis Bernard of Septimania in Toulouse during 844. Because the king’s location was both in reach and the same for long enough for news to get out, he seems to have been regularly beset with Marchers asking for charters; in the two months he was there he issued thirteen that we know of, and four more are known, including these two, which could also date to this period; see Jordi Rubió i Lois, "Índexs" in Abadal, Catalunya Carolíngia II vol. II, pp. 507-586 at pp. 511-513. All are of course edited in the same volumes, so I won’t give further references here. For my arguments about his policy, see Jonathan Jarrett, "Settling the Kings’ Lands: aprisio in Catalonia in perspective" in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 18 (Oxford 2010), pp. 320–342, DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2010.00301.x at pp. 329-330.

9. Abadal, Catalunya Carolíngia II, Barcelona: Església catedral de la Santa Creu II, cit. under ibid. Particulars XXII but not Particulars XXIII.

10. I meet this expectation from students a lot: a question about religious versus secular motives is always likely to confuse them since, having never experienced it themselves except as a vague part of the English state and education system, they mostly can’t conceive of religion except as a tool of secular power through indoctrination. However, it can’t be said that they don’t have academic company, as Jack Goody, The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe (Cambridge 1983) and Robert B. Ekelund, Robert D. Tollison, Gary M. Anderson, Robert F. Hébert and Audrey B. Davidson, Sacred Trust: The Medieval Church as an Economic Firm (Oxford 1996) will always be there to remind us.

11. Of course the two aspects crossed; but you can’t understand the economic one without belief as a factor. See Ian Wood, "Entrusting Western Europe to the Church, 400–750" in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6th Series Vol. 23 (Cambridge 2013), pp. 37–73, DOI: 10.1017/S0080440113000030 and indeed behind that David Herlihy, "Church Property on the European Continent, 701-1200" in Speculum Vol. 36 (Cambridge MA 1961), pp. 81–105, DOI: 10.2307/2849846.