The day I write this is, by various accidents, turning into a day for the dead, in which what I have before me is mainly writing stuff for the sake of people no longer with us. This happens sometimes, I suppose it can only happen more over time and eventually perhaps I will be the person being written for, so it behoves me to do my best. For a start, therefore, I only found out the other day that Neil Faulkner had died. I never met him but I saw a really good program he did with my then-colleague Roger White about the archæology of Romano-British Wroxeter, in which they just wandered around the site amiably but fiercely arguing about its interpretation; it was one of the best showcases of the academic endeavour and how we advance knowledge in its current Occidental paradigm that I’ve ever seen, and ever after that I thought of him as a good thing. The Guardian has an obituary for him that suggests at least one other person, and probably lots more, did too. But this post is not about him, but about someone whom I did meet and who was, in a way I don’t suppose he ever knew, part of my own academic story.

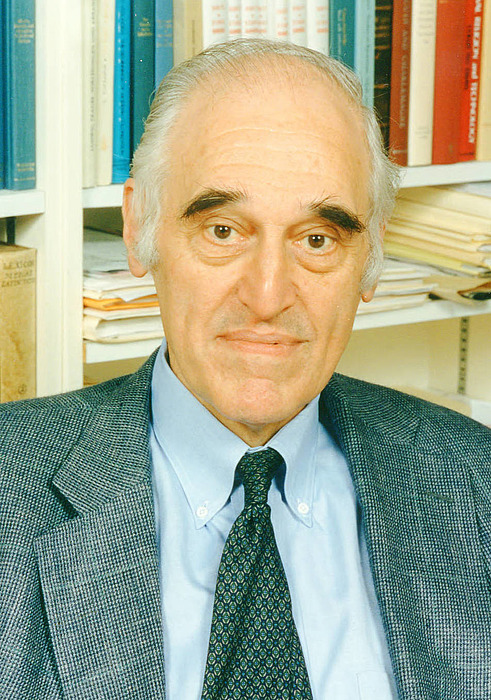

I won’t try and do a full run-down of Peter Linehan’s career, not least because there were plenty of write-ups of it when he died in 2020 – though somehow, I only just found that out when looking him up for something I’ve been writing elsewhere, on which more in due course. If you’ve never heard of the man, however, a few details might not go amiss. He studied medieval Iberian history, and the core of his work was on the Church politics of León and Castile in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, which is why I rarely have the pleasure of citing him here. In the 1980s he became one of the few Anglophone scholars in the field whom Spaniards would cite on the back of that, but he did range more widely.1 He was a particularly good source of archive war-stories, half of which he seemed to have poached from the late great Richard Fletcher, with whom he was a close contemporary, but with plenty of his own too; this made my experiences with the Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, when I had them, less frustrating for having some sense that this kind of thing was part of a researcher’s formation, a kind of rite de passage through which we all went. But he was at his best, probably, in print, where he combined widespread erudition with a delicious but needle-sharp wit that could leave foolish conjectures or bad scholarship in general punctured on every side. It’s not that Linehan necessarily solved every historiographical problem he encountered, but he was really good at showing weaknesses in previous solutions, and did so with great enjoyment and enjoyability. What he wasn’t good at was doing this briefly, which is why his masterwork, a critical review of eight or nine particular areas of debate in the interpretation of historical sources for the Iberian Peninsula’s Middle Ages, entitled History and the Historians of Medieval Spain, weighs in at 748 pages, a big number even in this day of huge books and more so when it came out in 1993.2 I assume that he was somehow involved with Oxford University Press at that point and managed to push it through whatever objections they may have had to it in that form, but I am glad he did, because every few pages there’s something that makes one pause and close one’s eyes in academic glee. I don’t have a copy to quote, alas, because it was expensive new and is probably more so now, but you can find this sort of thing in all his work.

The cover of the selfsame book

However, I don’t usually give space to obituaries these days unless the unfortunate deceased is someone whom I feel touches my own story in some way, and Peter Linehan, though as I say he possibly never knew, is indeed one of the people without whom I would not now be doing what I do. My first – and actually almost my only – encounter with him came during my M. Phil. at Cambridge, when I was trying to come up with a topic for my Short Essay and Professor Rosamond McKitterick was determinedly trying to steer me away from the Insular history which had up till that time more or less consumed my interest. Even then I was expressing an interest in frontier spaces and also charters, and so she pointed me at Catalonia, as a frontier space of the empire she herself knows best but one where, as she then said, “there’re thousands of charters that no-one’s using”. Trouble was, she didn’t know the area and its scholarship at all well, so she couldn’t approve my suggested topic; instead, she sent me to Peter Linehan.

The way to see Dr Linehan; the main gate of St John’s College, Cambridge, image byDicklyon – own work, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wkimedia Commons

I remember that meeting as an archetypal Oxbridge experience. Having made my appointment – or, given the basket case I then was, quite possibly having had my appointment made for me by Rosamond, I don’t know any more – I turned up at Dr Linehan’s rooms in St John’s College and was offered a seat on a sofa at one end of them, while he sat at the other end of the room on a window seat, pretty much as far away from me as he could be, wreathed in sunlight. I remember it as a huge room, though we could hear each other perfectly well so my junior memory must have stretched it, and I could barely see him in the glare. Anyway, with some trepidation I explained what I thought my questions were and how I thought I might go about it – on the basis of almost no reading, I should say, because then there were really only two short pieces about early medieval Catalonia in English – and asked him, at the end, “So, I suppose my question is, do you think it’s viable?” And he said, “Yes, I think it should be, as long as you can read Catalan. Can you?” And I, with remarkable self-confidence for the tremorous but stroppy boy I then was, said, “I don’t know, but I’ll find out,” and went away with a reading list mainly consisting of Ramon d’Abadal i de Vinyals.3 And the way I usually tell this story is that I worked through most of two books by d’Abadal and found that with good Latin and good French, and sometimes with Joan Gili’s idiosyncratic grammar, I could mostly puzzle it out.4 When I finally put together the essay bibliography I realised that some of what I’d read had actually been Castilian, but by then it was too late…

But long before that, I’d sent a mail back to Dr Linehan saying, more or less, I’ve got through the first few things and I think it will be OK, and he mailed back his approval for the project which I proudly took to Rosamond, and the rest became history, because it was meeting this evidence and scholarship that gave me my eventual PhD project, and from there the whole rest of my career. There might have been other ways it could have gone, but the way it did briefly hung on that brief mail of approval from Peter Linehan. I guess I always expected to run into him at least one more time to say thanks; but the two times I did, he was taken up with people who knew him well and on whom I didn’t feel able to intrude. So I never did say that thanks, and now I find I missed my last chance some time ago. Therefore, this will have to do. I don’t really envisage a readership for this blog among the dead, but if he were able to look in still somehow, I hope it would give him cheer. Thanks, Dr Linehan, and my students still enjoy reading your stuff when I make them…

1. His first book was Peter Linehan, The Spanish Church and the Papacy in the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought 3rd Series 4 (Cambridge 1971); his last, of which I had not heard either, was idem, At the Edge of Reformation: Iberia before the Black Death (Oxford 2019). Between the two he penned, as well as, like, eight other books not counting his two Variorum volumes of reprinted papers, both from remarkably early in his career, idem, “León, ciudad regia, y sus obispos en los siglos X-XIII”, transl. F.-J. Hernández in José María Fernández Caton (ed.), El Reino de León en la alta Edad Media VI (León 1994), pp. 409–57, which I mention not because it set my world alight especially but because it was almost the first case I’d seen of one of ‘us’ being published in Spain, in Spanish by the Spanish, presumably because they thought the work was important. I thought then that that would be one sort of measure of making it, and wanted to do likewise, and I suppose I sort of have, except, of course, not in Spanish…

2. Linehan, History and the Historians of Medieval Spain (Oxford 1993), review (favourably of course) by none other than Richard Fletcher in English Historical Review Vol. 109 (Oxford 1994), pp. 660-662, on JSTOR here.

3. Those works would have been Ramon de Abadal i de Vinyals, Els primers comtes catalans, Biografies catalans: sèrie històrica 1, 2nd edn (Barcelona 1965), and idem, Dels Visigots als Catalans, ed. Jaume Sobrequés i Callicó, 2 vols, Estudis i Documents 13-14, 1st edn (Barcelona 1969). The English pieces were basically R. J. H. Collins, "Charles the Bald and Wifred the Hairy" in Margaret T. Gibson and Janet L. Nelson (edd.), Charles the Bald: court and kingdom, 2nd edn. (Aldershot 1990), pp 169–188 and a couple of papers also by Collins about law and dispute settlement which included Catalonia alongside León that I’ve referenced many times before. I suppose there was also then, very new, Julia M. H. Smith, "’Fines Imperii’: the marches" in Rosamond McKitterick (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History volume II: c. 700-c. 900 (Cambridge 1995), pp. 169–189, DOI: 10.1017/CHOL9780521362924.009, which covers Catalonia in amongst the other Carolingian frontiers, and does pretty well at it. But I’m not sure I knew that piece this early.

4. Joan Gili, Introductory Catalan Grammar, with a brief outline of the language and literature, a selection from Catalan writers, and a vocabulary, 2nd edn (Oxford 1952), which is a good place to start but really really needs an update. Someone actually gave me this, though, and I wish I could remember who. I suspect they too are beyond thanking, now… Eventually I also gave in and paid the then-considerable money for the bulky and unsigned Catalan Dictionary: English-Catalan/Catalan-English (London 1994; originally printed Barcelona 1993), which is as far as I know still the only one you can get and is OK.