Such is the claim that Josep María Salrach makes of the document below, and Senyor Professor Salrach does not say such things without basis so I thought I could do no better than put it before you!1 The matter is a hearing of 25th March 874, held before Count Miró I of Conflent, brother of Guifré the Hairy, though this is before either of them hit the sovereign big-time with their appointment to more counties in 878. Instead, what we have here is the working of a just-still-Carolingian judicial apparatus, and it goes like this.2

“In the court of Count Miró and the judges who were ordered to hear, determine and rightly judge the cases, that is, Langovard, Bera, Odolpall, Dodó, Esteve, Fulgenci and Guintioc, judges, on in the presence of many other worthy men, the priest Kandià, Rautfred, Cesari, Goltred, Mauregat, Sentred, Ennegó, Sesgut, Daneu, Llop, the Saió Enelari, everyone who was seated in that court, there came a man, Sesnan by name, the representative of Count Miró, and he said: ‘Hear me, how that same Llorenç, that he ought to be a fiscal slave from the descent of his parents and grandparents, with his brothers and kinsmen, and they did service to the lord Count Sunifred, father of my lord by voice of whom my lord ordered me his representative to enquire.’

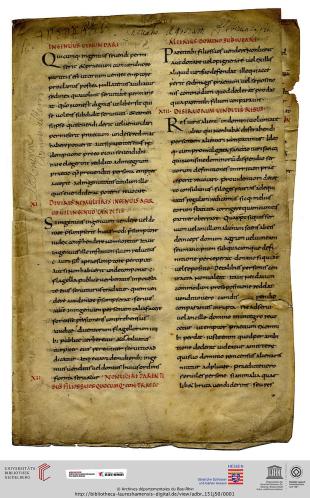

“Then the abovesaid judges said to Llorenç, who was summoned on behalf of himself and his kinsmen: ‘What do you answer to this?’ And he said in response: ‘I ought not to be a fiscal slave, and neither should my kinsmen, by descent from our grandfathers or grandmothers in the paternal or maternal lines, since I and my kinsmen, just as it says in the Law of the Goths, for 30 or fifty years have stayed in the houses in which we who are present among you were born without any blandishment or servile yoke, in the villa of Canavelles, with no count or judge summoning us.’Here is a completely non-Catalan copy of the Law, a fragment from Lorsch now in Straßburg, but it is at least ninth-century and secondly dealing with enslavement (V.4.x), so that’s not bad is it? For full reference to the text see n. 4 below. The MS is Archives Départementales du Bas-Rhin, 151 J 50, fo. 1r.

“We the judges indeed said to the representative Sesnan: ‘Can you present witnesses or documents or any index of truth by which you may prove that this same Llorenç, his brothers or his kinsmen ought to be fiscal slaves to your lord, and that they have been subjected to service within those legitimate years that the response mentioned?’ And he said: ‘I have no other proof than that I found in an inventory of my lord that his father assigned to him the woman Ludínia who was related to this kindred whom I prosecute.’

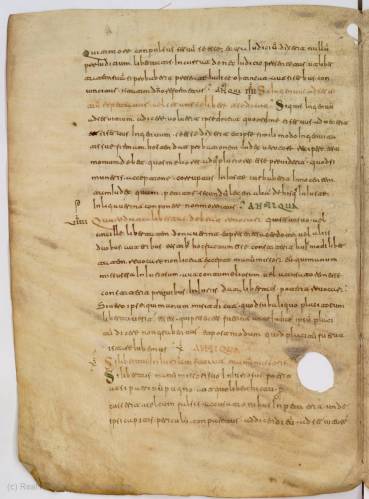

“We the judges indeed said to Llorenç: ‘How did that same Ludínia, who was your grandfather’s sister, come to be in that inventory if she was not a fiscal slave?’ And Llorenç responded: ‘I don’t know why it says that, but I do know one thing, that she was not a slave subject to service; but if servile condition isn’t carried from someone in the kindred to which I am connected to their children, then the servile condition doesn’t apply to their children.’And here is the exact bit of the Law that is about to be quoted, V.7.viii, from a late-ninth or early-tenth-century copy now in the Real Academia de Historia in Madrid, to which I can now link you because PARES have finally enabled stable URLs! It is Biblioteca de la Real Academia de Historia, Cod. 34, fo. 43r.

“So we searched in the Law of the Goths where it says: ‘If anyone wishes to bring a free person into slavery, let him demonstrate by what rule the slave came to him. And if a slave should claim himself to be a free person, and shows to the selfsame person proof of his freedom in the same way’, and the rest which follows.

“Wherefore we asked that same Llorenç if he might be able to produce such witnesses as the law says, that he or his kinsmen ought to answer for nothing to the fisc. He said: ‘I can’. He introduced four legitimate witnesses without any crime, that is, Guitsèn, Adaulf, Belès and Viatari, who swore by a solemn oath just as is written there. Then we the abovesaid judges said to Sesnan: ‘Can you produce more or better witnesses, or name a crime that prohibits testimony in the law, today or later?’ And that man said in his answers: ‘I can produce neither witnesses nor documents nor any index of truth whereby I may defame those same witnesses, or to subject those same persons to service neither in those same three hearings nor at any other time, today or hereafter. I thus, by the interrogation of the judges and in the presence of worthy men do recognise and quit my claim in the villa of Vernet, in the church of Sant Sadurní, and recognise that I have received the oaths which those same witnesses made truly by the order of my lord, and those things that I have done rightly and truly I do recognise and evacuate in the judgement of you or the presence of those written above.’

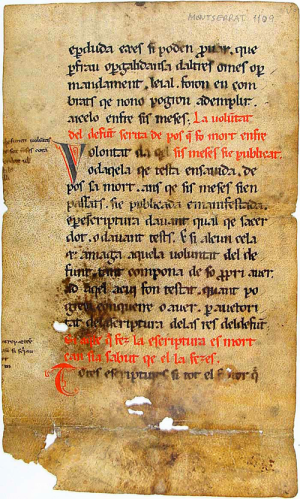

Lastly let’s just bring out that Catalan copy of the Law one more time… Abadia de Montserrat ([1]) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

“Recognition or evacuation made on the 8th Kalends of April, in the 34th year of the reign of King Charles.

“Sig+nature of Sesnan, representative of the lord count Miró for fiscal cases needing answering, who have made this recognition or evacuation and handed [it] over [to] witnesses for confirming. Miró. Guintioc. […]

“Protasi, conversus if God should be his companion, who have written this document of recognition or evacuation on both the day and year as above.”

Again, there is an awful lot here to play with. I like especially the representation of direct speech that, it becomes clear, can’t be, because they talk in formulae and refer to things that haven’t been reported, like the exact nature of Ludínia’s relationship to Sesnan. I also note that here both sides, both the state representative and the undowntrodden peasant, cite the Law of the Goths, and the judges know that the peasant’s cite is justified. As I have said, people generally do seem to have known about the thirty-year rule. I am also fascinated by the suggestion that Count Miró I had an officer whose business was the pursuit of fiscal claims, though the complex phrasing that Protasi (who was at this stage in the business of drumming up support for a monastery at Sant Andreu d’Eixalada that would not end well, and was a serious person about the public sphere) seems to have loved may be making as much of that title as it does of his own (which is, I should make clear, very hard to translate, so I may be glossing what is actually incoherence). And of course, the count has an inventory! But as we have seen before (when talking of later, but so what?) it’s not a very good inventory; the claim hadn’t been pursued for years and the only data the count had went back a generation and was inherited, rather than compiled, by the current administration. As I said a couple of posts ago, just because the Carolingian and post-Carolingian state had ambitions to systematic record doesn’t mean that they were necessarily very good at it.

And finally the actual location of the hearing, in its modern guise, Sant Sadurní de Vernet or as you would now find it in an atlas, It seems an impressive enough place to hold court! Saint-Saturnin de Vernet-les-Bains. By Baptiste Autin (Own work (Baptiste Autin)) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC-BY-2.5], via Wikimedia Commons.

For Salrach, what is most interesting here is the back and forth about service, servitium, which seems to be what defines slavery in practical terms here.3 There are several definitions floating around the case, it seems to me: the comital claim hinges on an argument by descent, and Salrach says that the relationship is found insufficiently close because of slavery not transmitting through the maternal line so that doesn’t work. They don’t actually say that, though, even though they could have because it too is in the Law of the Goths.4 And what they looked up in the Law doesn’t seem to relate either to that or what they did next, perhaps because although both sides were trying such arguments everyone knew that the thirty-year rule probably made them irrelevant anyway. The deciding factor was whether or not Llorenç’s kinsmen did servitium to the count in that time; they had people to say they hadn’t and Sesnan had nothing but the descent claim from a woman whose presence in a list of slaves wasn’t explicable. As I say, the comital archive wasn’t up to the job it was being asked to perform here.

From all this, anyway, and several other mentions of servitium, Salrach builds up a picture of the development of the obligations of the general populace to the count, seeing it as being a form of servitium generalised to all subjects of the public power (which the Vall de Sant Joan hearing qualifies as army service and the ‘lesser royal service’) and a more specialised, demeaning one that is what was at issue here.5 I’m not sure I would go as far as he does with this but it’s about the only attempt to work out what the counts could actually demand from their subjects that’s not based essentially on a template of Carolingian government assumed still to be running, so for me it still has great value as an idea to work with. Nonetheless, he’s right that this is a very interesting document, and it’s the hints, the drama of court and the attempts by people to swing old law in their directions in various ways and with various unexpected sorts of proof that make it interesting for me as much as the big point that Salrach believes it helps make.

1. J. M. Salrach, Justícia i poder a Catalunya abans de l’any mil, Referències 55 (Vic 2013), p. 128: “Aquest és, segurament, el document més interessant dels que coneixem de l’administració de justícia a la Catalunya Carolíngia.”

2. Pierre Ponsich (ed.), Catalunya Carolíngia VI: els comtats de Rosselló, Conflent, Vallespir i Fenollet, rev. Ramon Ordeig i Mata, Memòries de la Secció històrico-arqueolòico LXX (Barcelona 2006), 2 vols, doc. no. 81: “In iuditio Mirone comite seu iudices qui iussi sunt causa audire, dirimere vel recte iudicare, id est, Langobardus, Bera, Odolpaldus, Dodo, Stephanus, Fulgentius et Guintiocus, iudicum, vel in presentia aliorum multorum bonorum hominum, Kandiani presbiteri, Rautefredi, Cesari, Gultredi, Maurecati, Sentredi, Enneconi, Siseguti, Danieli, Lupon, Enalario saione, omnes qui in ipso iuditio residebant, veniens homo nomine Sesenandus, mandatarius Mirone comite, et dixit: «Audite me cum isto Laurentio qualiter servus fiscalis debet esse ex nascendo de parentes de abios suos, cum fratres vel parentes suos, et servicium fecerent domno Suniefredo comite, genitore seniore meo, ad parte fisclai per preceptum quod precellentissimus rex Carulus fceit domno Suniefredo comite, cuius voce me mandatarium mandat inquirere senior meus».

“Tunc supradicti iudices dixerunt Laurentio, qui est inquietatus pro se et parentes suos: «Qui ad hec respondis?» Et ille in suis responsis dixit: «Non debeo esse servus fiscalis, nec parentes mei ex nascendo de bisabios vel visabias ex paterno vel ex materno, qui ego et parentes mei, sicut lex Gothorum continet, per XXXa vel quinquaginta annis in domois in qua nati sumus inter presentes instetimus absque blandimento vel iugo servitutis in villa CAnabellas, nullo comite vel iuduce nos inquietante.»

“Nos vero iudices Sesenando mandatario diximus: «Potes habere tests aut scripturas aut ullum indicium veritatisunde probare possis isto Laurentio, fratres vel parentes suosu, ut servi fiscale seniori tuo debent esse, ut infra istos legitimos annos quod responsum dedit servituti fuissent?» Et ille dixit: «Non habeo alia probatione nisi inveni in breve senioris mei quod pater suus ei dimisit femina Ludinia qui fuit parentes istius parentele quem ego persequor».

“Nos vero iudices diximus Laurentio: «Unde advenit ista femina Ludinia in isto breve, qui fuit soror abie tue si ancilla fiscalis non fuit?» Et Laurentius respondit: «Nescio quomodo hic resonat, set unum scio, quod ancilla inclinata in servitio non fuit; sed si aliunde ad filios suos conditio servilis non avenit, de parentes quod mihi coniuncta est, non pertinent ad filios suos servilis conditio».

Nos autem perquisimus in lege Gotorum ubi dicunt: «Si quis ingenuum ad servitium addicere voluerit, ipse doceat quo ordine ei servus advenerit. Et si servus ingenuum se esse dixerit, et ipsi simili modo ingenuitatis sue firmam ostendant probationem», et cetera que secuntur.

“Proinde diximus adisto Laurentio si potuisset tales habere testes sicut lex continet ut nullum ex fisco persolvere debeat ille aut parentes sui. Ille dixit: «Possum». Introduxit legitimos quattuor testes absque ullo crimine, id est, Guitesindo, Ataulfo, Beles et Biatarius, qui iuraverunt a serie conditione sicut ibidem insertum est. Tunc nos supradicti iudices Sesennando diximus: «Potes alios habere testes ampliores aut meliores, aut crimen quod in lege vetitum est testificandi dicere hodie aut postmodum?» Et ille in suis responsis dixit: «Non possum habere testes nec scripturas nec ullum indicium veritatis unde istos testes diffamiare possim, aut istos ad servitium inclinare neque isto trinos placitos nec ulloque tempore et hodie et deinceps. Sic me recognosco vel exvacuo ab interrogatione udiucm et presentia bonorum hominum in villa Verneto, in ecclesia Sancti Saturnini, et ut sacramenta fecerunt isti testes veraciter recepi per iussionem senioris mei, et ea qui feci recete et veraciter me recognosco vel excvacuo in vestrorum iuditio vel suprascriptorum presentia».

“Facta recognitione vel exvacuatione sub die VIII kalendas aprili, anno XXXIIII regnante Karolo rege.

“Sig+num Sesenandi, mandatario domno Mirone comite ad causas fiscalis requirendas, qui hanc recognitione vel exvacuatione feci et testes tradidi ad roborandum. Miro. Guintiocus. […]

“Protasius, si Deus comes fuerit, conversus, qui hanc scriptura recognitionis vel exvacuationis iussus scripsi et die et annon quo supra.”

3. Salrach, Justícia i poder, pp. 126-134; see my very brief discussion in J. Jarrett, review of Josep María Salrach, Justícia i poder en Catalunya abans de l’any mil (Vic 2013) in The Medieval Review 14.09.16, online at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/18731, last modified 15 September 2014 as of 27 September 2014.

4. Karl Zeumer (ed.), Leges Visigothorum, Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Leges Nationum Germanicum) I (Hannover 1902, repr. 2005), transl. S. P. Scott as The Visigothic Code (Boston 1922), online here, II.2.iii, which also invokes the thirty-year rule for getting out of such an inheritance if a slave happened to have one.

5. Salrach also attacks this question with different cases, including the Vall de Sant Joan hearing, in Justícia i poder, pp. 87-90, 110-112 & 242-243 (conclusions).

Pingback: Preservation not by neglect | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

This is so cool. Thank you for sharing it. I love the way the careful wording demonstrates the concern Carolingians had for documenting, well, just about everything. And even though the nobility may not have been very good at it, it seems the judiciary did a pretty good job. If I had more time I’d be running through Alice Rio’s stuff to see if the wording/format has a basis in a formulary.

You wouldn’t find it in Alice’s stuff, though there are probably echoes in Marculf (there are echoes in Marculf of just about everything); this formula set is apparently Visigothic, especially the language of the quitclaim, and the best parallels come from the Formulae Visigothicae from Oviedo. For once I’m not sure this level of documentation is the Carolingians’ fault!

Pingback: ‘We saw with our eyes and heard with our ears…’ | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe

Pingback: From the Sources XII: successful crime and vicarious enforcement | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe