So, I have been promising this post for weeks, but at the very end of July 2019 I was in Barcelona to examine a doctoral thesis. Although the actual thesis was excellent, and its author now a collaborator of mine, the process was a little arduous, especially because of coming so close on the heels of the International Medieval Congress and then my holiday. But it was also a really good occasion and was the making of some very useful contacts, so it definitely wants writing up. The question is how to do so without running on for ages, because it’s a story of many parts, all worth explaining, and I think the answer is to say relatively little about the content, which those who care about can of course explore themselves, and instead try and tell the story as a process.1

Precursors

The very first step of the process, then, goes back as far as the spring of 2017, when a young Catalan by the name of Xavier Costa Badia turned up as a visiting doctoral student at the Institute for Medieval Studies at Leeds. He had come not least to work with me, though none of the arrangements had been made with me, but I was having about the worst professional year of my life then or since and we in fact only managed to meet twice. However, that was enough, apparently, to reassure both of us that we knew and loved the subject area and had interests in common. Subsequently, Xavier was drafted in to help edit the proceedings of a conference about the nunnery of Sant Joan de Ripoll, about which as you know I Care A Lot, and it was mainly because of his agitation that I got the invitation to be in that volume which constituted my first-ever Catalan-language publication (which Xavier translated).2 So when, in about the middle of that process, he approached me about being on his doctoral examination panel, I’d already accepted that I was going to have to say yes, and indeed, except for the weight of actual reading involved, I was quite keen to know what he’d written. Anyway, it was sorted out, and then in late spring 2019 the thesis actually arrived.

Reçerca

Now, this should definitely be read as anthropological comparison and not complaint, but, the usual word limit for a UK doctoral thesis is 100,000 words and with a bibliography that usually comes out at around 250 pages of double-spaced 12-point A4. I admit, mine was 308 including an appendix.3 But Xavi’s is 723, and that’s just the volume which now sits weightily on my bookshelves. I say ‘just’ because there was also an electronic component, a CD-R including a further 67 pages of PDF, which go to explain the 6002-fiche database of monastic sites he had compiled to source the actual thesis. So I had a lot of reading to do quite quickly. (I confess, I only sounded the database a little bit, just to see how it had all been done, which was, of course, methodically and as far as I could see, accurately.)

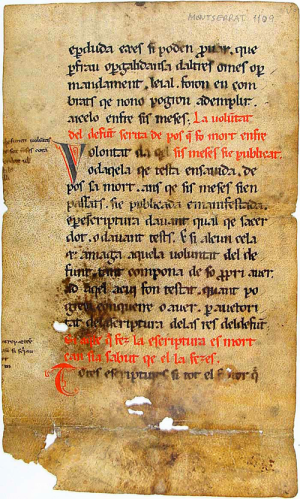

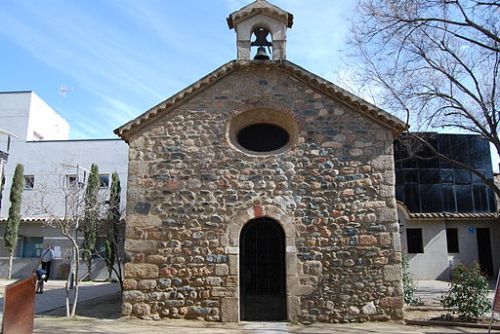

The remains of Santa Cecília d’Altimiris, perhaps the oldest monastery in what is now Catalonia which survived through to the early Middle Ages and one where I believe the subject of this post has spent some time digging; image from Monestirs.cat, linked through

So as you may gather from that, Xavi’s actual topic was monasticism in early medieval Catalonia, to which he was taking a landscape and archæological approach: this involved first defining what he meant by a monastery, secondly how we can identify them in the record either textual or archæological (not a simple question), thirdly which places were in and which out, and fourthly (longest bit of the first part), where, in topological terms, they all were. Then the second part was case studies, including the twin houses of Ripoll, and then finally conclusions. And I did enjoy reading it, because Xavi’s writing is clear and elegant and of course I learned a great deal, but I was also very relieved when I finally got to the end before I’d had to leave for the airport…

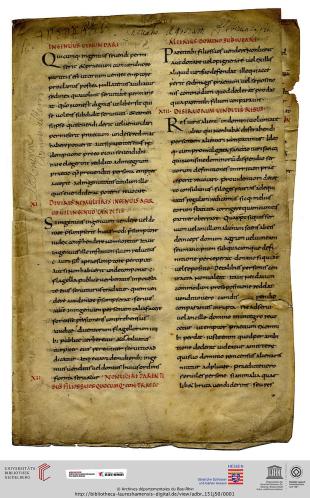

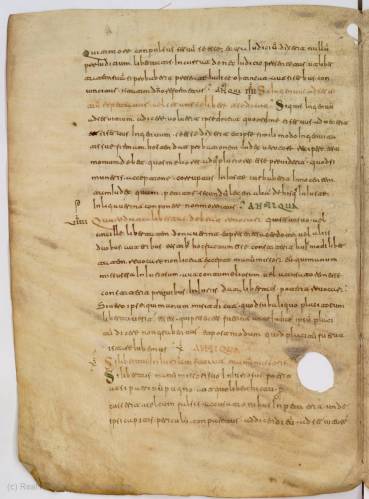

Notes for the defence, with page numbers and cross-references

And the reverse side, with something like a plan of my speech, also with page references

So by the end of that, I had a lot of notes of things to talk about, 11 pages of single-spaced 12-point in fact, and obviously, that was too much. And I spent most of the plane journey out distilling that into the questions I thought really were important, and working them into some kind of order, which generated the kind of squirrelly interlace around my notes which you see here and with which you may by now be horrifiedly familiar, but did mean that I arrived more or less prepared.

Procès

So I flew out the afternoon before and fetched up in the best place I’ve yet stayed in Barcelona (other than the Residència d’Investigadors, which really needs someone else to pay for up front), which is to say that it was clean, private (in the sense that it had a lockable door to the room, not always something I’ve found) and offered only just enough space to turn round in because of the inclusion of an implausible and just-about-functional en-suite. It was also over a street whose lively night-life echoed through the building only till about two a. m., which is actually pretty mild for Barcelona. I think all the power sockets and light-switches even worked; hopefully I still have a record of where it was somewhere… The result of this was that I arrived at least passably rested at the Universitat de Barcelona the next day, but then had to do the mental climb that is waking up one of my rudimentary foreign languages after a year or two of dormancy. The fact that some of the assembled academics didn’t speak that foreign language (Catalan) made that an uphill struggle, but by the time I actually had to talk, with a few lines worked out ahead of time, I could at least justify in Catalan my lapsing into English for the academic content, something of a relief all told.

So what actually happens at one of these dos is very unlike the UK process, where you just get closeted with your two examiners for an hour or two, they quiz you and you find out somewhere in there whether they think you passed or not. As far as I understand it, it’s basically impossible to proceed this far in the Continental system if the thesis isn’t going to pass; if that were likely, it wouldn’t have been put forward for examination and if you raise objections you’ll embarrass everyone, so, you don’t. (Not a problem with either of the two I’ve so far examined, I should say.) But that doesn’t mean that you can’t give the candidate hell, if you want, and there are between three and six of you to do it, as well – in this case five – before an audience usually including the candidate’s family and best academic friends, the latter of whom you’re terrorising for their turn at the process. Every member of the panel gives their views, and then at the end of it, the candidate has to give a response, for which they have been frantically scribbling notes while everyone speaks, at the same time as trying to protect their ego enough to cope. As you can tell, I don’t fully endorse the extremity of this process, especially since, after you’ve put them through all of this, the candidate has to buy their examiners lunch! (Though it was both good and welcome; but we’ll come to that shortly.)

Anyway, as I say there were five of us: in order of speaking Jordi Bolòs i Masclans, definitely the man you want for expertise on landscape archæology in Catalonia; me, for non-Iberian peninsula perspectives and some relatively keen knowledge of the Ripollès; María Raquel Alonso Álvarez, of the Universidad de Oviedo, representing the rest of the Peninsula (which is actually not that usual, in Catalonia); Marta Sancho, Xavi’s actual supervisor and thus the person who knows several of his sites like no-one else; and Josep María Salrach, who is mentioned on this blog in almost every other post (at least, those about Catalonia), and so probably needs no further introduction. And we said, roughly, that it was excellent and a landmark thesis (everyone agreed); and then…

-

- that the gaps on the map were interesting and that place-names needed closer examination (en Jordi);

- that there were almost no typos that I could find, itself remarkable, but that I wasn’t sure how much of the monastic landscape was actually Carolingian rather than local initiative (i. e. top-down royal policy versus bottom-up local piety (or politics4)) and wanted to know how far one could get models out of this area which might be used elsewhere (me, among several other more minor things);

- that there were important differences between the late antique or Visigothic phase and the new Islam-contemporary one of Carolingian Catalonia, not least a strange but very evident shortage of nunneries, and that in this respect both Muslim Iberia and incipient Asturias-León seem to have remained late antique (Professor Alonso; this had me wondering if royal control of the fisc was perhaps part of the difference, or so my notes tell me);

- that we also needed to think about why people even bcame monks or nuns in this world, as well as where (Professor Sancho; there were lots of jokes in this address which my Catalan wasn’t up to getting, too);

- and then there was en Josep.

Now I pause for breath here, because Josep María’s speech was a good bit longer than ours. But of course, it being Josep María Salrach, there was loads of good stuff in there, mostly complimentary but also encouraging us to think about visibility of sites; about how landscape is a phenomenon which only exists when observed because otherwise it’s just how the land is; that the late antique/early medieval difference might be the combination of reform Christianity and a frontier with Islam, which I really wanted more time to think with; that both-gender communities might explain some of the shortage of nuns (and here I respectfully disagree because I think we don’t really see any in Catalonia; Sant Joan just having some attached priests doesn’t count5); that Carolingian monastic ideals might be detected in the area by the copying of monastic rules (and indeed they might but, well, people have looked6); about whether gift and counter-gift was really different from sale in this world (to which I inwardly raised my old objection, that there were different ways of recording both so the choice must have been significant); and that the fact that frontier space could be claimed as part of the fisc wrapped monasteries into power in certain special ways (and here we’re into aprisio, and I’ve said everything I can say about that long ago).7

So as you can tell, I actually had more arguments with Josep María Salrach than I did with Xavier, and that was handy in a way as we then got sat opposite each other at lunch, but before then, after two and a half hours of having his work dissected, Xavi had to respond. He thanked us all for not looking too hard at his classification of monasteries, which was where he thought he was weakest, and then wrangled with each of our points briefly, including answering mine in English. The question several people had asked, none with any better suggestions, was about the county of Cerdanya, which was one of the big gaps on the map, just very few monasteries; it’s upland and mostly had a pastoral economy, but as several people had pointed out, that didn’t stop people founding monasteries anywhere else. And once he’d answered us all, we finally let him off the hook, now as Dr Xavier Costa Badia, and there was a lot of applause and some speeches of thanks and it was all good.

Conseqüències

Now, naturally enough the main consequences of all this have redounded on Xavier, who got not just his doctorate but a prize and presumably a pay rise on his next gig, and a small rook of publications.8 But this is my blog, so I really mean consequences for me.

Xavier himself, with that same doctoral thesis, after winning the Institut d’Estudis Catalans’ Premi Sant Jordi of the Secció Històrico-Arqueològica Pròsper de Bofarull d’Història Medieval with it

So, obviously I got paid for this—or maybe that’s not obvious, in fact, but I did—but there were also a bunch of other reasons this was a good thing. Firstly, and not least, I now have on my shelf a pretty up-to-date directory of monasticism in early medieval Catalonia, which has already proved useful. Secondly, I got a good lunch and a chance to drop in on the Biblioteca de Catalunya out of it, and found somewhere borderline-acceptable to stay and somewhere very good to eat in Barcelona. Thirdly, however, I got a chance to have a long and fairly friendly argument with Josep María Salrach, to the amusement of Marta Sancho, and I hope both of them thought them better of me afterwards; but I’m fairly sure Josep María did, because he brokered my getting the rest of the Catalunya Carolíngia more or less for free, it wasn’t long after this that he asked me to write my second piece of scholarship to be published in Catalan, and he has remained a help whenever I’ve needed to ask ever since. And, fourthly, it has meant that whenever I’ve been asked who the exciting up-and-coming figures in my field are, I’ve been confident in naming Xavi; and as a result of this, the poor lad has got dragged into several collaborations he otherwise might not have, including, mirabile dictu, with Castilians – but that needs separate reportage, and will, I promise, eventually get it. On this occasion, however, much of this was yet to come, but I went home with a good feeling for the future and a sense of many useful connections made. It was definitely worth the panic reading post-holiday. I’m not sure I could do it now, though!

1. Most of Xavier’s work, understandably, is in Catalan, but if you would like a sense of what he does and only read English, there is an early sample in Xavier Costa Badia, “Non-regulated Female Religiosity in the Catalan Counties in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries: A Territorial and Network-Oriented Approach” in Svmma: Revista de cultures medievals Vol. 15 (Barcelona 2020), pp. 35–54. The actual thesis, meanwhile, is Xavier Costa Badia, “Paisatges monàstics: El monacat alt-medieval als comtats catalans (segles IX-X)”, tesi doctoral (Universitat de Barcelona 2019), and there is a presentation of it in Xavier Costa Badia, “Paisajes monásticos. El monacato altomedieval en los condados catalanes (siglos IX-X). Tese de Doutoramento em História apresentada à Universidade de Barcelona (Espanha), Julho de 2019. Orientação das Professoras Blanca Garí e Maria Soler-Sala” in Medievalista no. 28 (Lisboa 1 July 2020), pp. 419–434, DOI: 10.4000/medievalista.3396, which is in Spanish but is at least online and open access.

2. Jonathan Jarrett, “La fundació de Sant Joan en el context de l’establiment dels comtats catalans”, transl. Xavier Costa in Irene Brugués, Costa and Coloma Boada (edd.), El monestir de Sant Joan: Primer cenobi femení dels comtats catalans (887-1017) (Barcelona 2019), pp. 83–107.

3. Not that I imagine you’ve forgotten, but as I’ve mentioned it, that would be Jonathan Jarrett, “Pathways of Power in Late-Carolingian Catalonia”, unpublished Ph.D. thesis (University of London 2005), online here, rev. as Jonathan Jarrett, Rulers and Ruled in Frontier Catalonia, 880-1010: Pathways of Power, Studies in History: New Series (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer for the Royal Historical Society, 2010).

4. I’m thinking here largely with the work of Rob Portass, who would have been another brilliant person to have on this panel, and of whose work the most relevant bit would be Robert Portass, “The Contours and Contexts of Public Power in the Tenth-Century Liébana” in Journal of Medieval History Vol. 38 (Abingdon 2012), pp. 389–407, 10.1080/03044181.2012.710551.

5. People have been suggesting it does ever since José Orlandis Rovira, “Los orígenes del monaquismo dúplice en España” in Homenaje a la memoria de Don Juan Moneva y Puyol, Estudios de derecho aragonés (Zaragoza 1954), pp. 235–248, but I still don’t think it’s right; we’ve just got no evidence that Sant Joan’s priests worked out of the nunnery rather than the neighbouring parish church. People use its example to justify other possible cases but it’s actually the most likely of the lot.

6. Admittedly, I’m thinking primarily of Cullen J. Chandler, Carolingian Catalonia: Politics, Culture, and Identity in an Imperial Province, 778–987, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought 4th Series 111 (Cambridge 2019), DOI: 10.1017/9781108565745, which it would have been hard for anyone at this gathering yet to have taken into account, but Anscari M. Mundó, “Regles i observances monàstiques a Catalunya” in Eufèmia Fort i Cogul (ed.), II Col·loqui d’Història del Monaquisme Català, Scriptorium Populeti 7 (Poblet 1972-1974), 2 vols, I pp. 7–24, didn’t come up with much either as I recall.

7. See Jonathan Jarrett, “Settling the Kings’ Lands: Aprisio in Catalonia in Perspective” in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 18 (Oxford 2010), pp. 320–342, DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2010.00301.x, one of several pieces I’ve written I really wanted just to end a dispute and actually haven’t really been heard in it.

8. To name but a few beyond those already cited in n. 1 above, three chapters in that same essay volume cited in n. 2 above; a first appearance in print in Xavier Costa Badia, “Los monasterios nacidos a través de pactos en los condados catalanes del siglo IX: Reflexiones en torno a la pervivencia de un modelo fundacional visigodo en tiempos de la reforma carolingia” in Hortus Artium Medievalium Vol. 23 (Zagreb 2017), pp. 328–335, DOI: 10.1484/J.HAM.5.113724; a historiographical review of his main subject in Xavier Costa Badia, “El monacat als comtats catalans altmedievals: un balanç historiogràfic” in Índice histórico español Vol. 132 (Madrid 2019), pp. 49–78, on Academia.edu here; and now a book I will have to read, Xavier Costa Badia, Poder, religió i territori: una nova mirada als orígines del monacat al Ripollès (segles IX-X), Mvnera 1 (Barcelona 2022).

![The ruins of the castle after which Castellfollit del Boix, location of the property Borrell had grabbed back, is named. By Elmoianes (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0-es], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://tenthmedieval.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/640px-castell_de_castellfollit_-_castellfollit_del_boix_cic_20110926_00607.jpg?w=500&h=375)