This is the last one of the Catalonia trip edits, so from here on it’ll be back to the more mundane writing and stolen graphics… So I thought I’d give you some hardcore diplomatic work as well as a pretty picture, by way of demonstrating that I wasn’t just being a tourist.

The last three days of my trip were spent commuting into Barcelona, rather than touring, you see. There was actually a bit of city-walking as I made an attempt to track down Professor Feliu in person, and that took me past the gardens of the Palau Reial and past a good deal of modern and impressive office architecture, but I didn’t have time to look at anything very much. I will say this, in case you ever find yourself trying to find a street address in Barcelona: the blocks may contain seven or eight different shops, offices or even houses each; or they may contain a single giant hotel. They are still numbered at a notional two numbers per block, and various crazinesses with “-bis” and so on are sometimes used to separate addresses but basically it’s impossible to count doorways to see how far you have to walk, or to tell when you’ve found your address unless it wears a name. Yes, I did have to walk some way. But once I’d got back into town (Professor Feliu in the end came and found me in town, for which I must thank him—we had a good chat, although it had to be in French) I got myself to the Biblioteca de Reserva in the old University building. I have to say, even with a Cambridge background, this building is quite impressive. It wasn’t so much the age of the buildings, or even its splendour though a big hallway with status of Isidore of Seville, King Alfonso X the Wise and other Spanish or Classical intellectual luminaries staring down from either side, will stick in my mind. It mainly struck me because it was so cool and quiet and lush, and full of plants and trees. For example, when I stepped out of the library to take a break, this was the scene that greeted me:

You see, I can cope with this as a study environment. So, what was I actually doing? Well, I mentioned above that I had some plans to work on the charters of Sant Pere de Casserres, and they are in the Biblioteca Universitària de Barcelona. The staff there were very helpful, though more cautious than those at Vic; I had to surrender my passport and could only see a few at once. There turned out to be just enough from before my self-imposed date threshold to establish that it was a good point to choose as after that the diplomatic changed sharply, and although at the time of writing I haven’t had time to do any detailed analysis of the contents, I already know that there’s enough material here for two papers and one of them will serve for Leeds 2009. (If only I had my 2008 paper so well advanced…) So that was pretty encouraging.

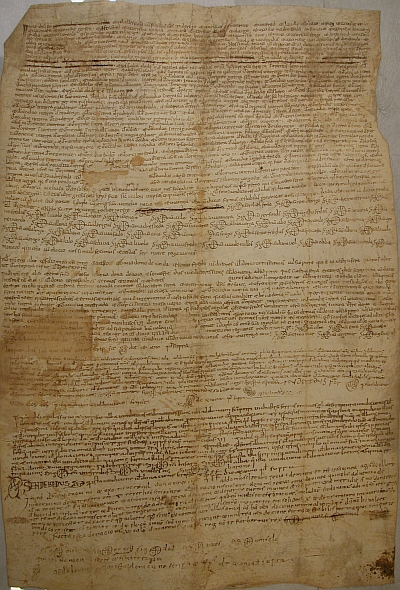

Now, let me show you how a charter scholar does his work :-) Firstly, have a charter:

This is Biblioteca Universitària de Barcelona, Pergamins C (Sant Pere de Casseres) núm 20, and there is a full-size higher-resolution version under the image here if you want to study it closely. So the first thing to do is scribble some description, but as you can see it I’ll spare you. Note however that this one’s especially good for the range of scripts; all these people seem to have signed for real and they none of them show the same hand, which is interesting, because so much of the writing we have is in formal scripts, it’s fascinating to me that that isn’t what people use when they sign their names. Are they going up a register so as to stand out? Or are they reverting to their ‘usual’ hand? I don’t know.

Next question is, what does it actually say? And if you want to do this properly, you have to transcribe it. So, off the file created on the laptop I’d borrowed specially for this purpose, I give you the diplomatic transcription:

In dei om~ptis N~ne SciaNT [NT in ligature] o~nis d~m credentes quia mot? e~ placit: in sede uico Int~ cenobio Sci~ petri / kastru~ serres & Vutardo tarauellense de alaude q~d conda~ Reimu~d? drog? relinq~d ad p~fata / cenobii. Dicens p~phat? Vutard? q~d facere non potuit quia karta pr~ inde fecit ad socru~ suu~ olibane de cha/praria, In hac uero audiencia fuit brenar~d? uicescomes qui cum Reinardo abb~e sua~ exibuit leg / testimonia ante Wifredo iudice quia quando [change of pen here] ipsa karta fuit facta q~d Vuitard? ostendebat Reimu~d? prephat? / auctor demenserat & alienat? a sensa?, & ideo ego Vufred? iudex p~ condicionib? editis recepit ipsos testes & confirmo ipso / alaude in potestate sci~ petri & potestati de reimu~d? ut ab hodierno die in antea eu~ habeaNT [NT in ligature] que~ ad modu~ / at ordinauit p~phat? Reimu~d?. Condiciones uero que p~tin~ & ad Negocii reseruate ut conditeruNT [NT in ligature] in ipsa cenobio. Et si quis hoc disru~pere [..] libra~ auri p~soluat & hec consignacio firma p~maneat, Est aut~ ia~dictus / alaudes in ipso angulo ant~nunio , & suNT [NT in ligature] domos & t~ras & uineas & molinos cu~ t~minas & p~tinenciis & exios ut / ios. Kartam uero qui ostensa[.] i~ placito fuit in~ne olibane caprariense euacuata fuit & p~ma~sit / p~missu~ e~ cu~ testib? qui in condicionib? resonaNT [NT in ligature]. Facta deficione .iii. id~ marcii, anno, XXXIIIJ / rei~ Radb~to rege. *Guifredus l~ta q~ & iudex q~ cu~ guitardo recep~ / testes & sub SS

/

*hECFREdVS GRACIA DEI AbbA SS *SUNIARIVS m~cho SSS / *VUIlielmus X

//

SSS P&r? l~, Rogat? scripsit, & sub scripsit X die & anno q~d supra

A few conventions there may need explaining. It’s supposed to be what’s on the document, exactly, unless it’s in brackets. Square brackets are my comments, angle brackets hypothetical readings. Slashes, tildes and asterisks are my exceptions to the exactness—the first are line breaks and the second are a representation of the marks of abbreviation, all of them alike, which is sloppy I know but forgive me a limited typeface. The asterisks indicate a signature not written by the main scribe. The question marks are one abbreviation mark I have preserved as is, that is, they’re not actually interrogation points but a mark meaning -us has been omitted. So there’s your transcription, and you may be able to trace this on the document (and if you think I’ve got it wrong I’m happy to be corrected). Now what does it actually mean? With the advantage of having read quite a lot of Catalan charters, I can fill in the gaps, but this is still a story in itself. If I just skip to translating, it goes:

In the name of omnipotent God. Let all believers in God know that there was held a hearing in the See of Vic between the monastery of Saint Peter of Casserres & Guitard of Taradell over the alod that the late Ramon Drog left to the aforementioned monastery, Guitard saying that he could not do that since he made a charter of it to his cousin Oliba of Chapraria. In this audience, indeed, was Viscount Bermon, who along with Abbot Reinard displayed his testimony before Guifré the judge that when this charter that Guitard was showing was made, the author, the aforementioned Ramon, had become demented and was out of his mind. And therefore I Guifré the judge, through sworn oaths, received the witnesses themselves and I confirm the selfsame alod in the power of Saint Peter and the power of Ramon so that from this day into the future they may have it just as the aforementioned Ramon ordered. In fact, reserve you the oaths that pertain to the business so that they can be archived in the monastery. And if anyone [should come] to disrupt this, let him pay a pound of gold and let this verdict remain firm. The alod itself is moreover in l’Angle in Antuniano, and there are houses and lands and vines and mills with their bounds and appurtenances and exits and entrances. Meanwhile the charter that was shown in the hearing in the name of Oliba of Capraria was disavowed, and the promise of that remains with the witnesses who are recorded in the oaths. Definition made the 3rd Ides of March, in the 34th year of the rule of King Robert. Guifré, deacon and also judge, who with Guitard received the witnesses and signed below.

Hecfred by the grace of God Abbot signed. Sunyer, monk, signed. Guillem X.

Signed and subscribed Pere the deacon wrote and subscribed X the day and year as recorded above.

All right, I haven’t finished thinking about this document yet, but let me call out some points for you.

- Firstly, though I’ve translated fairly loosely in a couple of places there, this is very strongly styled. The drop into not just direct speech, but a direct imperative (“reseruate”, ‘reserve you’), is really unusual. Whoever wrote the text that this is derived from (see 4 below…) was apparently working from dictation more or less, and Guifré apparently wanted to wash his hands of it post haste: he ties up various loose ends as he thinks and gives instructions as if it were a memo, not a solemn court judgement.

- His dismissal of the case and the details of it might be explained because, for example, it was well known to all parties that Ramon Drog had indeed gone a bit doolally in his last months and quite possibly sold his lands several times over, and the question was going to be whether Guitard of Taradell could put this over on the judge. Guifré, working out that he’s been had, gives Guitard short shrift and basically banks everything with the monastery, including the warning that the witnesses will remember him admitting the charter to Oliba was useless. It’s a fairly weak claim anyway, that the land can’t be the monastery’s because it’s someone else’s when that someone else isn’t the plaintiff, but the defence isn’t so hot either is it, “oh well he was mad, your honour, mad he was, oh yes, well known it is how mad he was honest”. But the people saying this are the local viscount and the abbot of the monastery so there’s little hope for Guitard really. Once the monastery had convinced Bermon to show up, and his mother had founded the place so they have a connection, Guifré was really just filling in the blanks. It’s tough to be up against The Man in early eleventh-century Catalonia.

- Nonetheless, a few things here don’t add up. We don’t have the oaths of the witnesses; normally they would indeed be on a separate document, but it’s not here even though it was supposed to be kept in the monastery. Nor do we have any record of the gift to the monastery; Ramon made a charter to someone else, but the monastery have to rely on witnesses and heavy local enforcement, as well as claiming their donor later went mad. Where are these documents they should have, both before and after the hearing? You have to wonder whether it’s all entirely kosher, or if in fact this might be a Scheinprozess, a fake hearing intended to produce a document that proves property when other proof is lacking. And if they don’t have the oaths either, maybe it’s an entire fake, a document that records a hearing that never really happened.

- Because, you see, the document isn’t an original. But it has the signatures on it, I hear you say, how can it not be original? Well, yes, signatures. And look, one of them’s the abbot. Not the abbot named in the text, but a subsequent one. Unless one of the four (which is very few, and two of them at least are members of the monastery) witnesses was an abbot from elsewhere, this was written up and signed later on, and Pere seems to write other documents for Casserres which are basically copies of older charters to which they apparently refer. I haven’t worked this out yet, but there are incontrovertible examples.

So quite a lot going on there. Next, try this!

No okay, only kidding. But you can imagine how my heart sank when I saw it. In fact, though, it’s fascinating, at least to me. There are five separate transactions written up here, and one, the third, has autograph signatures, albeit only two and them both clerics. The trouble is, it postdates the first one on the parchment, but this huge parchment was clearly set up to take that big transaction, not the tiny one, which seems to have been fitted round and so must have been written up from something else after the date of both of them. That in turn means that they either used new witnesses, or the two clerics were both still around to sign again. So much for autograph signatures as a proof of originality!

And meanwhile, what are they actually doing? The first transaction is so huge because it has 40 donors and vendors (they’re all called both) and deals with 23 pieces of land. It must have been a huge occasion! Except that, having given all the boundaries ,when the scribe gets to the bit where he should record the prices paid for these lands, he gives up and writes instead, “p[ro]p[te]r p[re]cio sic inclos[um] in ipsas scripturas resonat”, ‘because of the price that is recorded in the selfsame charters thus included’. In other words, he’s making a big narrative out of lots of charters, this isn’t one huge occasion, it’s a story combining 23 separate transactions for the sake of a permanent record. One might have guessed this from the crossings-out that imply fairly clearly that the scribe has lost his place or the plan of how to deal with a source text in front of him, but then he goes and admits it for us. This is supposed to be a very material foundation legend built as a kind of pancarta and then they add four more transactions that had happened already as well onto it like they were making a huge one-sheet cartulary (which is basically what a pancarta is, in case you were wondering; the web seems to have no useful definition). No wonder they abbreviate so heavily! But what I haven’t figured out is who it is doing this. There was a church at Casserres before the monastery, and this document doesn’t mention monastery or monks in any of its parts. All these transactions are dated to before the monastery was established, but we’ve already seen that that doesn’t mean much. And there’s four separate scribes with clearly different hands and another two clerics in the signatures. What parish church has five working priests and extra staff? There’s another just across the way at Sant Pere de Roda with a similar number, and they even own land around this church, so what on earth’s going on? They can’t both be mother churches so close to each other!

I haven’t worked it out yet, but because I now have this stuff under my belt, I reckon I probably will. Just, maybe not right now…

And all right, I’ve finished now, I’m back in the UK even virtually now, back to the books and the blogs. I hope I haven’t driven you all off…