The first time I blogged about one of Steffen Patzold’s papers, he later told me, it came as rather a shock to him when one of his students pointed it out to him. The episode threw me into a temporary tiz about whether I should in fact be writing up these semi-public events, whether it was like tweeting a conference paper (then a hot controversy) and so on, and although I decided in the end to carry on on the same basis, still, now that I find myself wanting to write up another of Steffen’s papers I still pause. I hope that two things will keep him happy with this post; firstly, that this happened two and a half years ago so is kind of old news; and second, that it’s a highly enthusiastic write-up! But then, so was it last time…

Cover of Steffen Patzold, Presbyter: Moral, Mobilität und die Kirchenorganisation im Karolingerreich, Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 68 (Stuttgart 2020)

Those who don’t know Steffen except through my occasional outbreaks of praise for his work here, however, may get some idea of it from the fact that in 2008 he published a book entitled Episcopus which, just like that, became the definitive study of the evolution of the bishop’s office through the early Middle Ages, and then in 2020 followed it up with another called Presbyter doing the same for priests (with three other books in between just to keep busy).1 If Presbyter hasn’t yet had quite the impact that Episcopus had that may only be because, firstly, it’s still quite new and there was this pandemic in between; secondly, in this field there’s some strong competition for attention; and thirdly, obviously, there were lots more priests than bishops in the early medieval world and dealing with them as a phenomenon is consequently more complex.2 As part of that, Steffen has been deeply involved in a long-running project on local priests in the Carolingian world that I’ve been watching closely, which must keep bringing those complexities to his attention.3 Nonetheless, he is still capable of drawing big conclusions in the best traditions, rather than the worst, of institutional history, and this was what he was doing when on 24th March 2021 he spoke, virtually, to the Earlier Middle Ages seminar of the Institute of Historical Research. This was the first paper where I’d actually managed to navigate the IHR’s virtual ticketing system, mainly by mailing to beg for the link which for me never arrives, and it was well worth it.

I had to cast around for a while for search terms for a Carolingian Eigenkirche (and on what that is see below), before it suddenly struck me that this, Saints Marcellinus and Peter in Seligenstadt, is one, albeit a big one: it was founded by a layman, who from whose letters we know controlled the appointment, and that there is almost no sign of episcopal control – but because that layman was Einhard and everybody loves Einhard it isn’t usually counted against him! But as we shall see, maybe counting things like this against people was a later concern anyway. Image by Jörg Braukmann, licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 via Structurae

So having introduced Steffen himself I have to introduce his topic. His title was "Beyond Eigenkirchen: local priests and their churches in the Carolingian world". So what’s an Eigenkirche, you may justly ask? Well, it is a term coined by one Ulrich Stutz, who in 1895 published a book called Geschichte des kirchlichen Benefizialwesens (roughly, History of Church property in benefice, which could itself demand an explanation, so maybe just let me carry on).4 It set up a clear and persuasive theory of a long struggle by the Latin Christian Church to get itself clear of ownership by laymen, patrons who built churches but then expected to control them, their appointments and their revenues entirely. For Stutz that situation came from the adaptation of "Germanic" expectations about property and enduring rights in it to the clear separation of Church and state beginning in the Gospels, a situation that the Frankish super-king and then emperor Charlemagne tried to reform, but which his son Louis the Pious made worse again by letting lords keep tithes as an encouragement to build more churches. This was where the great outburst of concern about such issues in the eleventh century which we tend to know as the Gregorian Reform after Pope Gregory VII, one of its loudest voices, came from. Stutz’s book has been tremendously influential; it went into its fourth edition in 1995, a full century after its publication, something we could all wish for but few indeed hope for, even though it was technically never completed, and the essential narrative survives even in more recent work on the subject.5 And as Steffen delicately but definitively argued, it’s basically wrong.

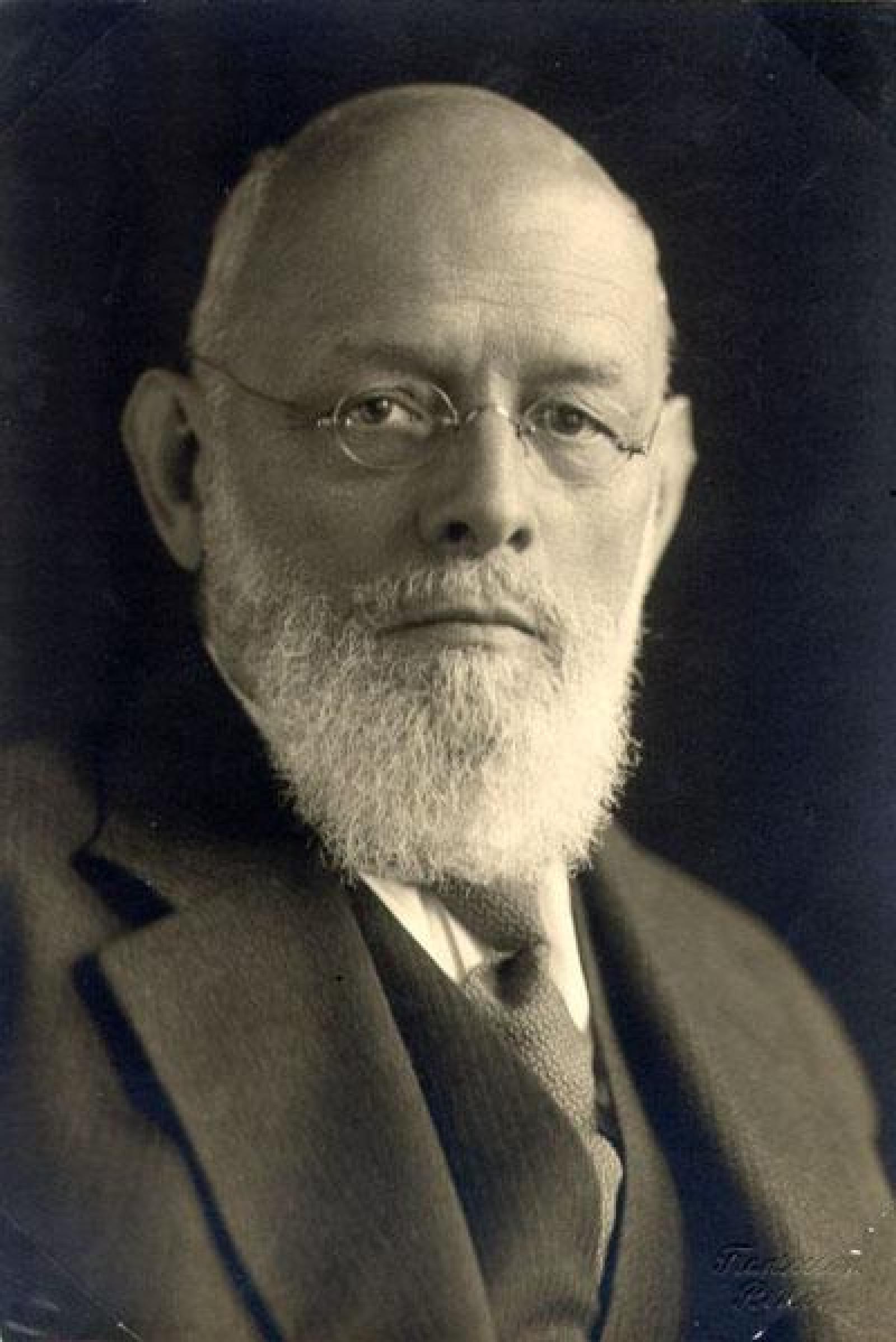

Portrait of Ulrich Stutz, from the Universitätsbibliothek of the Humboldt Universität Berlin. He does sort of look like someone’s just told him we were about to undermine his life’s work, doesn’t he? Sorry, Professor…

OK, big claim. On what does it rest? Well, firstly on the erosion of many of the accepted historical premises of the age in which Stutz wrote: that there was an ancestral "Germanic" set of expectations about property, a continual opposition of Church and state or at least Church and nobility even though the two groups were basically the same families, or that Louis the Pious was a weak ruler dominated by priests.6 But also, and this was Steffen’s main front of attack, on an equation between lord’s chaplains, what Stutz called because Carolingian legislation also calls "house-priests", whom Charlemagne, Louis and their churchmen regarded as dangerously free from oversight by bishops, often dangerously dependent on their lords (slaves given orders and that sort of thing) and certainly dangerously unqualified, and the more widespread and ordinary parish priest, or at least the local priest doing the ministry to the general population. For Stutz, since almost all churches were owned by lords and the priests their creatures, there was no meaningful difference. But since churches were built by many agencies, including the Church itself, but also their own future congregations, and in these places the bishops got to make appointments – we have very numerous records of bishops’ appointments of priests, so they must have worked somewhere – actually there were quite a lot of people doing that kind of work who were not running lords’ private churches, and these were the people on whom Steffen focused to make his case.

Some of these local priests were pretty major players in their own right and "local" is perhaps understating their importance, which was hardly one of being powerless flunkies. One guy called Erlebald, operating around the monastery of Lorsch, organised many donations there by a variety of people but also made some of his own, including numerous serfs and quite a lot of treasure. It’s hard to believe he was funnelling revenue to anyone else much, and maybe that was indeed a problem for his bishop, but not because he was under some lord’s thumb instead.7 However, these were the people on the ground for the Carolingian efforts to improve popular worship and belief, and we have lots of stuff written for and about them in the expectation of both their cooperation and effectiveness.8 Furthermore, there were lots of them: Julia Barrow asked for some numbers in questions and Steffen said that when the number of baptismal churches in some Carolingian dioceses was assessed numbers ranged from 50 to 230, each of which would have had several priests, each of whom would then have been set up as heads of new parishes, so, hundreds of priests in a diocese, thousands across the empire. As this implies, Steffen had argued that these reform efforts meant the Carolingians radically changing Church structures, breaking up big territories belonging to mother-churches with baptismal rights, which provided clergy to smaller less-privileged chapels (Italian pievi were mentioned, but I thought straight away of early English minsters9), and changing them into smaller structures centred on single churches with full rights over more limited areas (under the supervision of bishops, of course), the sort of thing we might call "parishes".

Not an Eigenkirche but somewhere from where churches and priests were regulated and instructed, Saint-Germigny-des-Prés, built by Bishop Theodulf of Orléans, whose statutes for his priests we have. Image « Germigny des Pres » by user:Cancre — own work, licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

So at the end of this we had not just what looked like a death-blow to a century-old shibboleth of early European Church history and a rehabilitation of the genuine effectiveness of Carolingian efforts to expand and improve, maybe even "correct" but maybe not "reform" the Church, but a plausible argument for the origins of the European parish. It’s not a bad evening’s work! Naturally, there were questions. Ed Roberts asked if house-priests could become "local" priests, to which the answer was that they certainly tried and some presumably did; Peter Heather wondered where the 11th-century boom in church-building came from if it wasn’t lords hungry for tithes, and Steffen pointed out some other ways to get rich off Church patronage as well as the way people could also set up their own; Erik Niblaeus wondered how monasteries fit, as lords or as tools of the reform effort, and Steffen said that structurally they were lords but worried the régime less as their priests tended to be better qualified; and I asked if an impression I had that mother-churches remained the first step in frontier-zones, with parish fragmentation following only later (thinking of my work on Manresa), which Steffen thought unlikely.10 I may have to show he’s wrong (or that Catalonia’s weird, one of the two). But he doesn’t make it easy!

1. Steffen Patzold, Episcopus: Wissen über Bischöfe im Frankreich des späten 8. bis frühen 10. Jahrhunderts, Mittelalter-Forschungen 25 (Ostfildern 2008); then Patzold, Presbyter: Moral, Mobilität und die Kirchenorganisation im Karolingerreich, Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 68 (Stuttgart 2020); between times, Patzold, Das Lehnswesen, Beck’sche Reihe 2745 (München 2012); Patzold, Ich und Karl der Grosse: das Leben des Höflings Einhard (Stuttgart 2013); and Patzold, Gefälschtes Recht aus dem Frühmittelalter: Untersuchungen zur Herstellung und Überlieferung der pseudoisidorischen Dekretalen, Schriften der Philosophisch-historischen Klasse der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften 55 (Heidelberg 2015).

2. I think here mainly of Julia Barrow, The Clergy in the Medieval World: Secular Clerics, their Families and Careers in North-Western Europe, c.800–c.1200 (Cambridge 2015).

3. I’ve probably missed some here, but the project has produced at least Steffen Patzold & Carine van Rhijn (edd.), Men in the Middle: Local Priests in Early Medieval Europe, Ergänzungsband der Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 93 (Berlin 2016) and Francesca Tinti and Carine van Rhijn with Bernhard Zeller, Charles West, Marco Stofella, Nicolas Schroeder, Steffen Patzold, Thomas Kohl, Wendy Davies and Miriam Czock, "Shepherds, uncles, owners, scribes: Priests as neighbours in early medieval local societies" in Zeller, West, Tinti, Stofella, Schroeder, van Rhijn, Patzold, Kohl, Davies & Czock, Neighbours and Strangers: local societies in early medieval Europe (Manchester 2020), pp. 120–149.

4. Ulrich Stutz, Geschichte des kirchlichen Benefizialwesens: von seinen Anfängen bis auf die Zeit Alexanders III. (Berlin 1895), 1 vol., online here. The title page says this is the "Ersten Band, erste häfte", but there seem to have been no more parts. The treatment is thematic rather than chronological, so what is argued is at least complete in itself. There is also Ulrich Stutz, Die Eigenkirche als Element des mittelalterlich-germanischen Kirchenrechts, Libelli 28 (Darmstadt 1955), non vidi, which given its date is I guess the key part on that subject extracted from the earlier work.

5. Stutz, Geschichte des kirchlichen Benefizialwesens: von seinen Anfängen bis auf die Zeit Alexanders III., ed. Hans Erich Feine, 4th edn (Aalen 1995), though as far as I can see all the new editions are just reprints with an extra essay at the beginning. Still, is four editions over a century even the top score to beat? We might instance Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, Una ciudad de la España cristiana hace mil años: estampas de la vida en León, 21st edn (Madrid 2014), originally published in 1928, parts of which you can find translated as Claudio Sánchez Albornoz [sic], "Daily Life in the Spanish Reconquest: Scenes from Tenth-Century León", transl. Simon Doubleday, in The American Association of Research Historians of Medieval Spain Library (Toronto 1999), online here, but I don’t know which edition Simon translated! According to Steffen, meanwhile, the obvious new work to replace Stutz, Susan Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West (Oxford 2006), doesn’t change the picture on this score very much. I should obviously know, but…

6. See here especially Mayke de Jong, "Ecclesia and the Early Medieval Polity" in Stuart Airlie, Walter Pohl & Helmut Reimitz (edd.), Staat im frühen Mittelalter, Forschungen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 11 (Wien 2006), pp. 113–132 and Mayke de Jong, "The State of the Church: ecclesia and early medieval state formation" in Walter Pohl & Veronika Wieser (edd.), Der frühmittelalterliche Staat – europäische Perspektiven, Forschungen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 16 (Wien 2009), pp. 241–254. A broader introduction can be found in Marios Costambeys, Matthew Innes & Simon MacLean, The Carolingian World, Cambridge Medieval Textbooks (Cambridge 2011), pp. 80-153.

7. For the abbey of Lorsch see Matthew Innes, "Kings, Monks and Patrons: political identities and the Abbey of Lorsch" in Régine Le Jan (ed.), La royauté et les élites dans l’Europe carolingienne (début IXe siècle aux environs de 920) (Villeneuve de l’Ascq 1998), pp. 301–324, though right now I can’t so whether it mentions Erlebald or not I can’t tell you. He is mentioned in passing as a relative and associate of Abbot Baugolf of Fulda in Innes, State and Society in the Early Middle Ages: the Middle Rhine Valley, 400-1000, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought 4th Series 47 (Cambridge 2000), p. 190.

8. We know this not least from the volumes of statutes they left behind which are now printed in Peter Brommer, Rudolf Pokorny & Martina Stratmann (edd.), Capitula episcoporum, Monumenta Germaniae historica (capitula episcoporum) 1-4 (Hannover 1984-2005), 4 vols, online from here.

9. On pievi why not see Rachel Stone, "Exploring Minor Clerics in Early Medieval Tuscany" in Reti Medievali Rivista Vol. 18 (Firenze 2017), pp. 67–97, online here? As for minsters, see John Blair, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society (Oxford 2005), pp. 79-134, 246-367 and to be honest much of the rest of the book too, or for short, John Blair, "Minster Churches in the Landscape" in Della Hooke (ed.), Anglo-Saxon Settlements (Oxford 1988), pp. 35–58.

10. But not just Manresa, or that wouldn’t be a great example since it’s so late; I think we also see it at the definitely-Carolingian Sant Pere de Rodes. See Jonathan Jarrett, Rulers and Ruled in Frontier Catalonia, 880-1010: pathways of power, Studies in History, New Series (Woodbridge 2010), pp. 93-97, and for proof of contemporaneity of at least the settlement with Louis the Pious, Imma Ollich, Montserrat Rocafiguera, Albert Pratdesaba, Maria Ocaña, Oriol Amblàs, Maria Àngel Pujols & David Serrat, "Roda Ciutat: el nucli fortificat de l’Esquerda sobre el Ter i el seu territori" in Ausa Vol. 28 (Vic 2017), pp. 23–40, online here.

Cut to the chase. Were they allowed to marry?

That is a cycle through which the Church has gone many times, and obviously when you’re in the reform stage, you’re in a position where there is clerical marriage but someone, at least, wants there not to be. All of which is preparatory to saying, I didn’t straight away know the answer and this actually turns out to be more complex than I expected. As far as I can tell without actually going to a library, the Carolingians did not outlaw clerical marriage, though many of their reformers had strong views against it; but despite that there still aren’t very many known cases of it. So the answer to your question seems to be yes, grudgingly, but not many did. Presumably concubinage is part of this answer somewhere, but I’d really have to go and look at stuff to be sure…

I think there’s an element of it being a regional thing. There were some areas in the early medieval west where clerical marriage was very common (I.e., Anglo-Saxon England, Wales, Brittany, parts of Northern Spain, Lombardy and the Alpine regions), and others where it was very rare even though it was allowed like Francia.

I’d agree with that, in outline. It does, however, immediately provoke the Toddler’s Question: "But whyyyy… ?"