On the way back home after meeting up with medievalists from the Internets in London the other day, as described already by one of those mysterious virtual persons, I came on an article of Chris Wickham’s I should have read years ago, tucked in the back of Wendy Davies & Paul Fouracre’s Property and Power with a title that might have led me to ignore it, did I not by now know not to ignore Chris’s stuff.1 Actually, although most of the sources it uses are indeed twelfth-century, his task is to argue back from those to how the Lucchese society he knows so well got this way, this way being feudalised in its tiny minutiae, dues, renders, labour and hospitality obligations differing from household to household. And that of course means that what we’re looking at is the good ol’ feudal transformation, discussed here a good few times. So I thought it might be time to collect up my writings here on that subject and mark out how Chris differs from the others.

- In the first of these posts I was complaining that the very detailed take of Jean-Paul Poly & Eric Bournazel on the changes in European society over the tenth to twelfth centuries hid the fact that they were being falsely compressed by the synthesis of the data Poly & Bournazel presented into a single phenomenon close to the year 1000 when actually what was being discussed was a almost-infinitely variable series of local experiences in which power and the organisation of society moved through recognisable, but not identical stages, at their own speed.2

- Then I took a much more theoretical vision of “el procés de feudalització” as offered by Josep María Salrach i Marès,3 and suggested that it was too schematised to work in most places but did give us a much clearer idea of what we are actually discussing than Poly & Bournazel’s immersion in Romance culture.

- Then I paid attention to Victor Farias trying to explain how the government of the counts in Catalonia could still meaningfully be differentiated from the landlordship of a lesser noble until the point of actual collapse, thus giving a working definition of the ‘public’ power that is supposed to have collapsed in this whole transformation thing.4 As I said there, I think a lot of this is warmed-over theory from Pierre Bonnassie, but it is a valid distinction and the question is merely whether it’s really a significant factor in the counts’ power. Me, I think not so much as control of castles, but it’s got to be in there somewhere.

- But then I found Josep María Salrach again explaining how even control over castles had changed,5 and that I found really quite subtle and interesting.

- And then Gaspar Feliu kindly sent me the fundamental article by Manuel Riu which suggests that a lot of feudal lords were probably heads of really quite ancient chiefdoms, in long-term dynastic succession, who adopted the new trappings of power but whose real importance came not from the new system, but from their heredity.6 In fact, then the system got its power from the endorsement of people like these, the already powerful. This, I think is not a whole explanation, but there must be cases where it is the best explanation, and if we try and stop explaining everything the same way we probably have a chance of getting somewhere

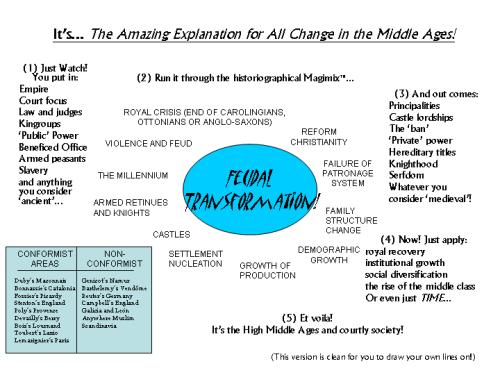

Otherwise, as I’ve mentioned, you wind up with historiography that unpacks like this:

and really, that doesn’t actually help us understand. In the lecture at Kings where I discussed this, I used the phrase ‘Occam’s Hairbrush’ to describe a logical tool that allows you to separate needlessly tangled entities; you really need it here.

So, where does Chris’s article fit into this tangle? Quite neatly, in fact. I don’t think he’s read Riu’s article, though I wouldn’t want to put money on this; I also don’t believe he much rates Feliu, despite their shared pessimism about aristocrats and peasants, though I know he’s worked with Salrach.7 None of this Catalan stuff necessarily percolates through to his Italian work, anyway, but what he’s saying is quite a lot like what Riu says. He looks at two little areas in the twelfth-century documents from Lucca where lordships sprang up that acquired these sort of menial dues and obligations, and shows that actually some of the lordships went back to before these dues were commonplace. What he is dealing with here is the angry insistence of Dominique Barthélemy that much of what is supposedly brought in by the so-called Transformation is not new at all, but found in the Carolingian era if not before. Barthélemy says it’s merely that the sources are recording things, that have always been there, differently.8 I would argue that if the documents change it’s because of a demand for a new sort of record, and that suggests a change in society. Pierre Bonnassie instead counter-attacked by showing that when new coins came into circulation, for example, the documents picked up on that almost straight away and we should expect them to be current in other respects too.9 (This was a really clever article and it is undeservedly obscure.)

Here, instead, Chris reaches a middle ground. The documents are indeed changing, but to write down these things regularises what was not necessarily regular before. A lord of Carolingian Lombardy probably could, if necessary or desirable, demand most or all of what these Lucchese patricians can; he may well have been able, absent any real restraint, to demand more. Once a compromise is reached between subject and lord here, both sides are limited, because even with a posse of armoured bovver boys you can’t hold down all your peasants all the time, and you’d get lousy service if you tried it; passive resistance to coercion can really drop your revenue.10 It’s in everybody’s interest that there be a compromise which is acceptable enough that it will continue without too much effort. So it is reached, household per household, and it is written down.

The questions that then hang off this are ones about how greater literacy affects society, and that is a big question all by itself.11 It’s not as if Carolingian Lombardy was alien to written surveys, sworn inquests recorded on parchment and so on.12 If Carolingian aristocrats here weren’t making such regular demands, and that of course is an argument from silence, there must have been something else going on that distracted them, or prevented them. Chris says it is the militarisation of local lordship that gets these things fixed; people before this didn’t need this kind of detail. But there must always have been local administrators, we see them at Perrecy apart from anything else, and they must have needed such records. So I’m not sure yet. But I am sure that he shows quite nicely how a lord in place, given new options about how to exercise his power, might then turn himself into something we then see and recognise as a feudal baron or whatever your local language of power calls him, on the basis not of oppressive force, but of status, repute, ability to protect his familia and pre-existent dominance of a less documented kind.

I think this is what is going on, I think it’s a question of changing modes of power, mainly brought about by increasing wealth giving increasing initiative and scope for variation on social conduct and the use of resources. But the question then becomes, why are there new options, are they really new, where have these `modes’ come from and why are they taken up now, and of course, how much does anything change for the poor pheasants? If il Patrone is the same all along, and you gotta have respec’ for il Patrone even if he wants all your sheep to throw a banquet for his daughter’s wedding, because we know what happens to people who don’ show no respec’, does it really matter to you if he makes you sign something saying how many sheep he’s allowed to take? I think it does, because it makes it negotiable or enforceable, but maybe the verbal settlements were too. So much more to work out still…

1. Chris Wickham, “Property ownership and signorial power in twelfth-century Tuscany” in Wendy Davies & Paul Fouracre (edd.), Property and power in the early middle ages (Cambridge 1995), pp. 221-244.

2. Jean-Pierre Poly & Eric Bournazel, The Feudal Transformation, 900-1200, transl. Caroline Higgitt (New York 1983).

3. Josep María Salrach, “Introducció: canvi social, poder i identitat” in Borja de Riquer i Permanyer (ed.), Història Política, Societat i Cultura dels Països Catalans volum 2: la formació de la societat feudal, segles VI-XII, ed. J. M. Salrach i Marès (Barcelona 1998; repr. 2001), pp. 15-67.

4. V. Farias, “Alous i dominis”, ibid. pp. 102-105, 107-111 & 113-116. He is improving here on Pierre Bonnassie, La Catalogne du milieu du Xe à la fin du XIe siècle: Croissance et mutations d’une société (Toulouse 1975-1976), 2 vols.

5. Josep María Salrach, El Procés de Feudalització (segles III-XII), Història de Catalunya 2 (Barcelona 1987).

6. Manuel Riu, “Hipòtesi entorns dels orígens del feudalisme a Catalunya” in Quaderns d’Estudis Medievals Vol. 2 no. 4 (Barcelona 1981), pp. 195-208.

7. Salrach translated one of Chris’s articles into Catalan, alongside one of Bonnassie’s and one of his own and some others, in a dossier on slavery in L’Avenç no. 131 (Barcelona 1989).

8. He says this most forcefully in “La mutation féodale a-t-elle eu lieu? (Note critique)” in Annales: Économies, sociétés, civilisations Vol. 47 (Paris 1992), pp. 767-777, but perhaps most accessibly in “Debate: the feudal revolution. I”, transl. J. Birrell, in Past and Present no. 152 (Oxford 1996), pp. 196-205.

9. Pierre Bonnassie, “Nouveautés linguistiques et mutations économico-sociales dans la Catalogne des IXe-XIe siècles” in Michel Banniard (ed.), Langages et Peuples d’Europe: cristallisation des identités romanes et germanique. Colloque International organisé par le Centre d’Art et Civilisation Médiévale de Conques et l’Université de Toulouse-le-Mirail (Toulouse-Conques, juillet 1997), Méridiennes 5 (Toulouse 2002), pp. 47-66.

10. For more on this, see James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance (New Haven 1985), but I owe the phrase ‘armoured bovver boys’ to a lecture by Amanda Brett in my second undergraduate year at Cambridge. It may be the only thing I remember from her lectures, but that puts her ahead of several other lecturers and no mistake.

11. Classically treated in Michael T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England, 1066-1307 (London 1979) or Jack Goody, The Logic of Writing and the Organisation of Society (Cambridge 1989), and some critique in Rosamond McKitterick, “Introduction” in eadem, The Uses of Literacy in Early Mediaeval Europe (Cambridge 1990), pp. 1-10.

12. On which see Chris Wickham, “Land Disputes and their Social Framework in Lombard-Carolingian Italy, 700-900” in Wendy Davies & Paul Fouracre (edd.), The Settlement of Disputes in Early Medieval Europe (Cambridge 1986), pp. 105-124; rev. in Wickham, Land and Power: studies in Italian and European social history, 400-1200 (London 1994), pp. 229-256.

You’ve posted it before, of course, but I always love the Feudal Transformation diagram. Still need to clear the hurdle between where I get the joke and a number of the references to where I can give a nice evidence-based disquisition or even ramble concerning my thoughts on the matter (which interests me a lot). Someday…

I suppose I could accompany that with wondering whether there is any book, either by a single author or a collection of articles on the theme, that really focuses on the Feudal Transformation debate and would be suitable as an introduction. Since Jean-Paul Poly & Eric Bournazel’s work, despite the promising title, doesn’t seem like the right thing to pick up first.

It’s come up in my courses, but not as something picked apart to excess. Too much of my personal reading on the topic has been the Anglo-Saxon–>Norman transition.

There are two small clusters of articles on the Transformation, couched as a debate, one in English and one in French. The French one is Poly & Bournazel versus Barthélemy, and so mostly illuminating about small bits of France and how Duby’s students can fight with each other. Barthélemy also contributes to the English one, which was all responses to an article by Thomas Bisson, but as three other people do too and not all work on France, it’s more useful. References:

Bisson, T. N., “The `Feudal Revolution'” in Past and Present No. 142 (Oxford 1994), pp. 6-42

Barthélemy, D., “Debate: the feudal revolution. I”, transl. J. Birrell, in Past and Present No. 152 (Oxford 1996), pp. 196-205

White, S D., “The ‘feudal revolution’: comment. II” in Past and Present No. 152 (Oxford 1996), pp. 205-223

Reuter, T., “Debate: the ‘Feudal Revolution’. III” in Past and Present no. 155 (Oxford 1997), pp. 177-195

Wickham, C., “Debate: the ‘Feudal Revolution’. IV” in Past and Present no. 155 (Oxford 1997), pp. 197-208

Bisson, T. N., “Debate: the `Feudal Revolution’. Reply” in Past and Present No. 155 (Oxford 1997), pp. 208-234

Some, but I don’t think all, of these are online at FindArticles for what help that may be.

Luckily I have Jstor access. PDFs all neatly arranged in a folder to be read. Thanks, much appreciated!

I remember, late, that there is also a recent review article by Simon MacLean in Early Medieval Europe; full cite is:

S. MacLean, “Apocalypse and revolution: Europe around the year 1000” in Early Medieval Europe Vol. 15 no. 1 (Oxford 2007), pp. 86-106.

That’s probably as up-to-date as you can currently get in English!

This has got me thinking more about when it actually makes sense for a lord to write down details of what the peasants owe him. If you start from the principle that a lord’s rough economic aim was to take as much of the surplus of the peasants as possible while leaving them still able to survive (the lord wants neither to kill them nor for them to get richer and hence less biddable), then writing things down is actually a bad idea, because it makes it harder for the lord to grab any additional surplus on the basis of ‘custom’ if the peasants do start to do better. Writing things down in detail only makes sense for the lord if he’s worried that he’s going to lose the dues he already takes on a customary basis: written dues provide a ceiling for what can be claimed, but also a floor below which what is claimed cannot fall.

In which case, maybe what changes is that there is more competition from other lords in the same area. There are certainly more secular lords in France in the period (and in Tuscany and Catalonia as well?), while everywhere with the monastic reforms there are new and newly aggressive monastic ‘lords’. So are the detailed records of dues mainly about lords protecting themselves from other lords by specifying exactly what their ‘share’ of the local peasantry is? If you have twenty ‘lords’ in a eleventh century pagus rather than two or three in the Carolingian one you may need this kind of specificity rather than relying on less detailed verbal agreements.

I like this, and will credit you if I wind up arguing it, but I think it’s a secondary cause. The reason there are more lords is not because the structures are disintegrating and anyone can get in on the act, though this is a factor in some places like the Midi I suppose. It’s also and perhaps mostly coming from the general increase in resource base: there is now enough surplus to make being a local lord on a small territory viable whereas in 900 maybe there wasn’t. If you have twenty lords, it’s because there’s enough to support them and their armed retinues; before maybe there was only enough to support ten, and therefore the `public’ power was still a better deal than trying to go it on one’s own resources. At the basic end of things I still think what’s going on is that economic growth increases the range of options available to everyone, and that this inevitably privileges those who can pay for military force with the new revenue. All the same, what you say is a consequence of this process that I think is extremely plausible and that I don’t think I’ve seen suggested before…

Pingback: The glorious 46th ed of 4SH « Testimony of the spade

It seems rather obvious that a written document is a security that can be traded or sold (or stolen or burned) in a way that a verbal agreement cannot.

Well, indeed, but in an age where few people can read it is perhaps less trustworthy than the consensus of a number of witnesses. A document can after all be faked, and many many cases in the early medieval material show documents being challenged, even ones that were technically authentic. There is a threshold of generalised literacy or, at least, familiarity with documentary processes, that has to be crossed before documents become a security in themselves, rather than just a way to spread the consensus among your potential witnesses.

First stipulating to my almost total ignorance, in the lay readings I’ve done I’ve noted that the lords often tried to keep the documents in a strongbox, and peasants, in riots and rebellion, tried to destroy the documents. Whether that is the general case I cannot say.

I have developed the strong suspicion that one of the more important questions about the witnesses is whether they were carrying swords. I’ll confess to some confusion as to how we would know how verbal agreements turned out if we didn’t have a written record.

Incidentally, thanks for this ‘transformation’ blogging. I’ve been interested in this period for some time but unable to think of the right questions to ask, so this is all very interesting to me.

The point about burning charters is a fair one, though all the examples I can think of are modern. The witnesses have to be people whose word would be respected; the article by Chris Wickham in Wendy Davies’s and Paul Fouracre’s The Settlement of Disputes in Early Medieval Europe has, if I remember rightly, a case where a witness is refused because of immoral character but that was in a very procedurally-developed system. The ultimate aim of a legal system, after all, is to maintain peace; if it fails it has to deploy a lot of continuous coercion. Early medieval society doesn’t really have that apparatus of enforcement, and lasting settlements require a consensus that the outcome is acceptable to enough of the community to hold it down.

Lastly, yes, indeed, you are quite right: our only clues to the workings of unwritten agreements are when later documents refer to them having been made. In that line, and also relevant to my point about consensus there, you may find this post illustrative.

In considering this I realize, first, that the ‘replies’ get narrower with each iteration, and secondly, that the examples I might offer come from periods of “eroding” feudalism, times when economic conditions suggested to peasants that they would rather pay feudal dues in coin than in kind. Presumably, in times when people were eager to enter feudal relationships with more powerful people, there would be a lot less bickering and arguing about the whole matter.

The case of Sant Benet de Bages is interesting. You wonder if they kept the original verdict for a reason, or simply because it seemed too valuable to lightly discard. Heaven knows I have quite a bit of stuff in the second category.

Paying in coin is good when prices are going up, because your render costs you less produce to get; but paying in kind is better when prices are going down. I think that that’s independent of erosion of feudal ties; but there may be social factors about protection and what justice one can hope for from other channels that make people eager for lordship. The idea of frontier colonisation by bold pioneers doesn’t make a lot of sense in these circumstances—it’s hard to be less protected and more vulnerable—which is why historians like Gaspar Feliu have been arguing that frontier settlement must have been under lordship all along.

As for preservation at Sant Benet, well, they did keep a lot. Elsewhere in the blog you can find me using the phrase ‘preservation by neglect’, but here I think it’s simpler; after Aió had died, they would have full property of the estate anyway, and then the old charter would be more useful than the new one because of its tenure being more ancient. On the other hand, any descendants of Aió and Guifré might be able to challenge Sant Benet for it just as Aió had unless the new one were kept too. Sant Benet were covered both ways.

Pingback: Seminar CCLXXI: feudalism beats capitalism for most of history | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe