I suppose it is not inappropriate that after lamenting Josep María Salrach’s death I return to a long-stubbed post in which I put one of the books he allowed me to get for free, and in whose publication he was a major part, to work.1 This comes, you see, out of that brief patch of research leave I had back in 2022 which I spent trying to find Count-Marquis Borrell II and his contacts in the newly-available charters from the county of Barcelona, and it’s one of the bits where that exposure to new evidence shows that, unfortunately, I was wrong about something. It’s not huge, but I do like to try and keep honest about this stuff, so you get the confession.

If you have a really long, like thirteen-year-long, memory of this blog and its record of my activity, you may remember that for at least that long I have had strong oppositional views to a particular theory about place-names in Catalonia, and potentially other places, which derive from the Latin word palaciolum, apparently "little palace". For most scholars it is accepted that the term relates to centres of fiscal extraction, collection or concentration, where renders were collected or brought for the use of the ruling powers, and that such a locus would therefore originally have been at the heart of such a place.2 We have a "broken palace", however, and things like that, so the place-name doesn’t always have to have derived from a going concern.3

Here is one such palace-that-is-estate-centre, albeit from rather later and in Aragón, the Palacio de los Hospitalarios in Ambel, image by Ecelan – own work, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 v ia Wikimedia Commons.

from Wikimedia Commons. For more details, see that older post of mine.

The theory I don’t like came out of a research group at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and it holds that the Catalan examples actually derive from the presence of Muslim garrisons in these places. There is a philological argument for this, via an Arabic derivative from Latin palatium, balat, but in al-Andalus that seems to have referred to public roads, not estates, and is very rare; I never understood why the derivation from this very rare Arabic derivative of the Latin made more sense in a Latin-speaking area than, y’know, the actual Latin.4 But leave that aside for now The project claimed there are ninety-odd of these place-names, which I believe but can’t verify because they never actually published the list.5 I had a look in the indexes of the Catalunya Carolíngia less the Barcelona volumes a long time back, though, and I found forty-eight, and now a search in the CatCar database gets 132 hits for palacio, some of which will be the same place plural times, so 90-odd is quite plausible. The project team were, however, remarkably light on evidence of any Muslim connection, and elsewhere I’ve critiqued the heck out of this idea; the only reason I haven’t published it, other than overcommitment and exhaustion, is that it seems to be part of a larger argument about continuity of the fisc in Catalonia which I just don’t know how to finish.

As close as the team got to publishing a list was this distribution map of place-names in palatium and palatiolum in Catalonia, taken from Cristian Folch Iglesias and Jordi Gibert Rebull, "Arqueològia, documentació escrita i toponímia en l’estudi de l’Alta Edat Mitjana: els casos dels topònims pharus, monasteriolum i palatium" in Estrat Crític Vol. 5 no. 2 (Barcelona 2011), pp. 364-377 at p. 370.

The critical plank of the argument about these names, however, is that while maybe one, maybe just two, have shown archæological evidence of Muslim presence (not easy to establish, of course, mostly a matter of burial rite, which requires actual burial, but still), rather a lot of them can be associated with erstwhile Roman villas.6 And, just as English place-names in -chester seem pretty much always to refer to erstwhile Roman forts in the locality, I reckoned that was probably good enough for a general explanation here: an ex-villa looks like a small palace, may also often be an estate centre or still be where renders are collected, isn’t that just easier than assuming an otherwise unattested massive spread of Muslim fortifications where they sometimes buried people?

We're somewhere in this neck of the woods; the long built-up stretch vertically down the middle is modern-day Palou, which is where our document says the land is, and that's really as close as we can get; all its boundaries are identified by neighbours, not more durable map features. So, it was in here somewhere.

Nonetheless, an absolute blanket statement like that was always likely to be wrong with so many examples, and even one Muslim-rite burial, in play. The Autonoma project team mentioned that several of the Palau place-names were associated with Arabic personal names, and I just forgot about that plank of the argument till I found myself looking at one, a land sale between two people quite unconnected to Borrell II but dealing in land, "in the county of Barcelona, in Vallès, in the term of Torre d’Azar, which they call Palou."7 Now, I’m not an Arabist or even a Hispanist, but I would say, "z" is almost never used in Latin or Romance names, there’s no Latin, Frankish or Gothic name I know which would easily degenerate into Azar (except maybe Nazarius, and the missing "N" is a real problem there), and while I don’t know of an obvious Arabic or Berber one either I’m fully prepared to accept that that’s what this is.8 And, obviously, it is a fortification. In fact, I wonder if finding this document in the Barcelona cathedral edition where it was first published is even what gave the Autonoma team leader the whole brilliant idea.9. Be that as it may, I have to concede the point, wherefore the reference of the title to an old old academic joke. Maybe you know the one. It supposedly originates with a mathematician called Ian Stewart, and goes like this:

A mathematician, a physicist, and an astronomer are riding a train through Scotland. The astronomer looks out the window, sees a black sheep in the middle of a field, and exclaims, "How interesting! Scottish sheep are black."

The physicist looks out the window and corrects the astronomer, "Well, at least some Scottish sheep are black."

The mathematician looks out the window too, and corrects the physicist, "In Scotland there exists at least one field where one sheep is black… on at least one side."10

Likewise, at least one of these sites would appear actually to have been a tower owned by someone with a name favoured by those of Islamic belief rather than Christian. Of course, the name doesn’t make him Muslim, his owning a tower doesn’t make it a garrison, and whatever the truths there are it’s also still possible that the tower was put on the site of a Roman villa that was already being called Palaciolo; but that case is no more and arguably less supported from this document than the Muslim garrison one, so if I ever do want to publish this I have to at least admit the possibility.

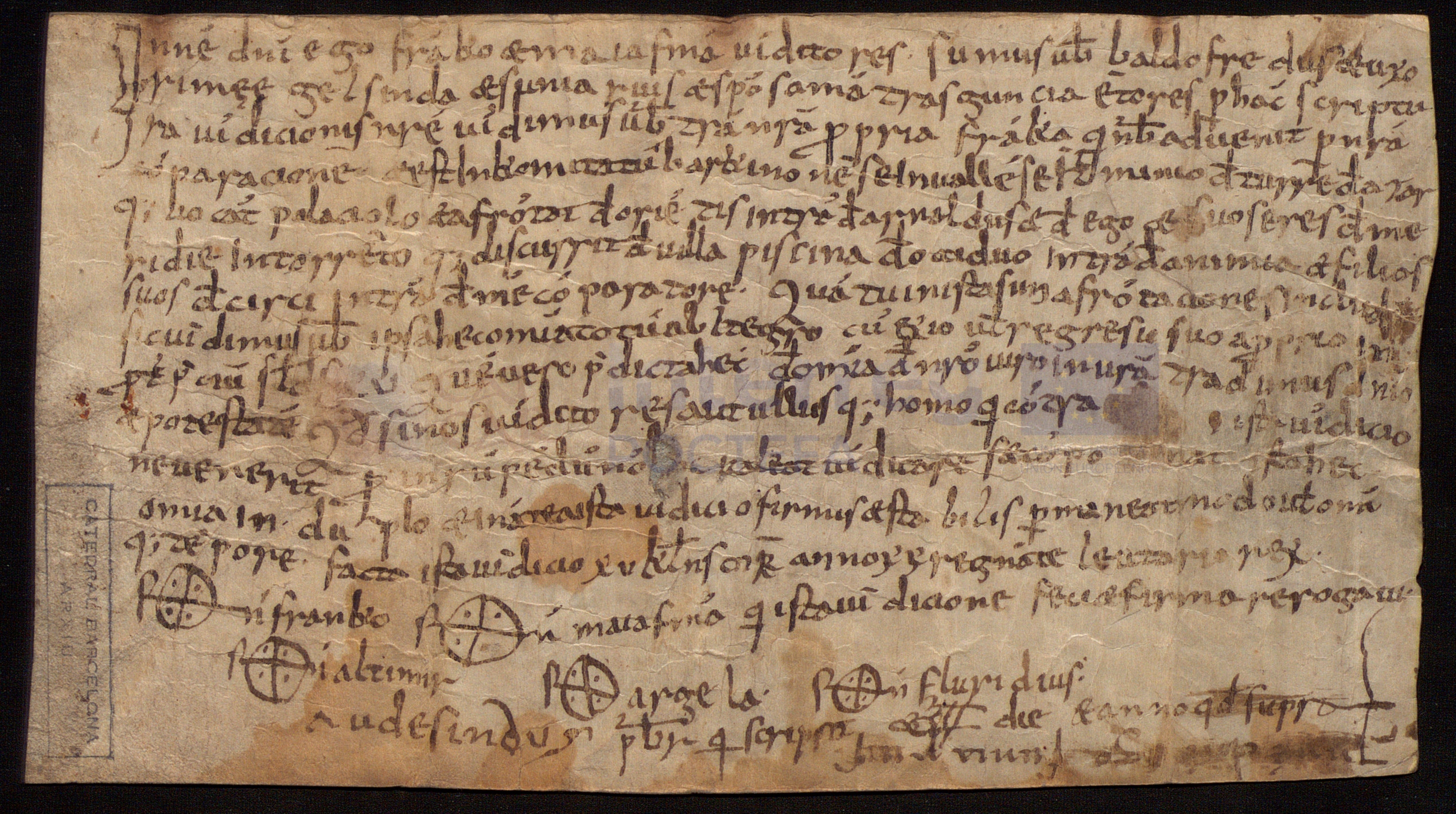

The actual document, Arxiu Capitular de Barcelona, Pergamin 1-3-30, hotlinked from the CatCar site, which I hope is OK. You can’t give direct links to that database, but you could find it in the Documents by choosing volume 7 in the drop-down and entering 616 in the search box.

Still, this is not a total loss even if it messes with a pet theory and it’s nothing to do with Borrell II’s people, because it’s also a very interesting charter diplomatically speaking. In the first place, apparently it’s a palimpsest, that is to say, it’s written over an earlier, erased document. I have to take the editors’ word for that, because even in the quite nice facsimile of it reproduced above from the CatCar database, I can see no sign of the remnant first line of the older document by someone called Sunyer which the editors could see up the left-hand edge (presumably under the archive stamp… ?)11 But if that isn’t enough to entertain you, it’s also one of those "charters we shouldn’t have", because it’s actually marked up on the dorse as useless, with a note from someone in the Barcelona cathedral archive reading, "Nothing for the Chapter."12 Why it didn’t then get thrown out is anyone’s guess; good old preservation by neglect, presumably, or perhaps the question was just one of whether it needed to be included in some other list or inventory, but whatever it was we might be quite lucky still to have it. So I will probably wind up using this document to prove some things anyway, in due course; but for now, it stands against me. Well, never mind: this is how we learn, and hopefully you have learned a little along with me on this occasion!

1. Ignasi J. Baiges i Jardí and Pere Puig i Ustrell (edd.), Catalunya carolíngia Volum VII: el comtat de Barcelona (Barcelona 2019), 3 vols.

2. It’s picked up in Pierre Bonnassie, La Catalogne du milieu du Xe à la fin du XIe siècle : Croissance et mutations d’une société, Publications de l’Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail Sèrie A 23 & 29 (Toulouse 1975-1976), 2 vols, as most things are, at pp. 144-153 of vol. I. For palacios further west, my standard reference is José Ángel García de Cortázar and Esther Peña Bocos, "El palatium, símbolo y centro de poder, en los reinos de Navarra y Castilla en los siglos X a XII" in Mayurqa Vol. 22 (Palma de Mallorca 1989), pp. 281–296, online here.

3. Palofret, near Terrassa, on which see Joan Soler i Jiménez and Vicenç Ruiz i Gómez, "Els palaus de Terrassa: estudi de la presencia musulmana al terme de Terrassa a través de la toponímia" in Terme Vol. 15 (Terrassa 1999), pp. 37-51, online here, though I don’t (as you will see) follow them all the way to their conclusions.

4. I think the first statement of this case was actually in Bonnassie’s Festschrift, in Ramón Martí, "Palaus o almúnies fiscals a Catalunya i al-Andalus" in Hélène Débax (ed.), Les sociétés méridionales à l’âge féodal (l’Espagne, Italie et sud de France Xe-XIIIe s.) : hommage à Pierre Bonnassie, Méridiennes 8 (Toulouse 1999), pp. 63-69.

5. I have the numbers from Cristian Folch Iglesias and Jordi Gibert Rebull, "Arqueològia, documentació escrita i toponímia en l’estudi de l’Alta Edat Mitjana: els casos dels topònims pharus, monasteriolum i palatium", Estrat Crític Vol. 5 no.2 (Barcelona 2011), pp. 364-377, but even then it’s not actually stated there; I had to count it off their distribution map p. 370 fig. 3, included below.

6. Although the team have written quite a few versions of this, I think all the basic information you need to support this is in the two pieces I’ve cited above. My older post references some of the other papers. At Folch and Gibert, "Arqueològia, documentació escrita i toponímia", p. 371 they do refer to a survey which surveyed eight sites and found Roman remains at none but early medieval remains at one, some or all (they don’t specify), ceramics of the eighth and ninth centuries, not that those are easy to date. And my previous investigation found at least one which was definitively a new foundation as well, so that certainly has to be allowed for. What none of that is, however, is evidence for Islamic foundation.

7 Baiges & Jardí, Catalunya Carolíngia VII, doc. no. 616: “Et est in komitatu Barkinonense, in Vallense, in terminio de Turrem de Azar, que vocant Palaciolo.”

8 For the basics of personal naming in the area see Josep Moran i Ocerinjauregui, "L’antroponímia catalana l’any mil" in Imma Ollich i Castanyer (ed.), Actes del Congrés Internacional Gerbert d’Orlhac i el seu temps: Catalunya i Europa a la fi del 1r. mil·leni (Vic 1999), pp. 515–525.

9. It was available to them as Àngel Fàbrega i Grau (ed.), Diplomatari de la Catedral de Barcelona: documents dels anys 844-1260 Volum I: documents dels anys 844-1000, Fonts documentals 1 (Barcelona, 1995), doc. no. 106.

10. A Reddit that I found says they found it in Simon Singh, Fermat’s Last Theorem (London 1997), citing Ian Stewart, Concepts of Modern Mathematics, 2nd ed. (New York City, NY, 1981), where indeed it is on p. 286, apparently far from the only mention of sheep in the book in fact. His version is classier than mine…

11. Baiges & Jardi, Catalunya Carolíngia VII, doc. no. 616, n. 3: "In nomine Domini. Ego Suniarius". They have better eyes than me (or possibly an ultra-violet lamp). I can’t give you my normal page reference, though, because for reasons I should probably explain next post I’m currently not with my books. I’m therefore using the CatCar database, online here, but that doesn’t permit direct hyperlinking. You have to go in through the Plataforma Virtual and search, sorry.

12. Ibid., editorial commentary, "Al dors: «Saeculi X» (s. XVII) i «Nil pro Capitulo» (s. XVII)", with the same regrets about citation as in the previous note. The classic one of these for English scholars is the so-called Fonthill Letter, which I talked about in this even older blogpost, and which is still in the Christ Church Canterbury archive despite at some point in its history being graded, "inutile", useless, in a similar exercise.