So, the last post recorded a paper that I was pleased to have made the time to hear. The same is less easy to say of this one. How can I put it? I like old rock bands. Now you can divide old rock bands into four groups, if you obsess enough about such things: those who despite having been going more or less continuously for years are still inventive and productive (Gong, most obviously for me; Hawkwind, to a lesser extent); those who have been going more or less continuously for a long time doing the same thing over and over (Status Quo, ZZ Top) among whom a subset have lost, to death, personality conflicts or reality, their creative cores and should stop for the sake of their once-good name (I will name only Thin Lizzy here, in either of their current touring incarnations). Then there are those who have lately reformed, and either can still cut it (Electric Prunes, Omnia Opera) or who really can’t but presumably needed the money (Blue Cheer…). Every time I risk a gig by some such venerable name, I wonder which of these it’s going to be, but one has to go because there may never be another chance (and every gig is unique anyway).1

I am less used to applying this scheme to academics, not least because they very rarely return to the field after time off, but it was in my mind after this paper, which was on the same day as the previous one. Long-memoried readers will recall, perhaps, that early in the life of this blog I blogged a book of interviews with various notables of the so-called New History.2 One of the interviewees was anthropologist and social historian Jack Goody, whom I had already noticed has recently put a new book out called Renaissances: the one or the many?,3 and another was Peter Burke, so when I discovered that Professor Goody, who has a local emeritus chair but is nonetheless rarely in these parts, was speaking about his new book at CRASSH and that Professor Burke was responding, I thought it would be interesting to go and see what that was like.

Professor Goody had, he told us, been in a quandary about this paper. He didn’t really want to just give a talk about the book, so had written another, then been persuaded that people probably wanted to hear about the book so glumly opted for the original after all, which he had then left at home, leaving him only some notes for the other one and his own considerable learning to produce an actual talk more or less on the fly. This he did while sucking on something, cough sweets or similar, throughout, so that it was often rather hard to tell what he was saying even once he had made up his mind. The basic argument, I think, was that the term ‘Renaissance’ involves an awareness of what is past so that it can be revived (however faulty that awareness might be), and that this involves records and therefore literacy, which is one of Professor Goody’s oldest concerns. An interesting sidetrack here took us off to China, where as he observed a pictographic script has allowed an empire of many languages to remain united for centuries, for various values of unity, because even when its inhabitants can’t understand each other speaking they can write their speech down in the same script. It’s a point, though not one germane to the title. Oral societies, he argued, have perpetually to reimagine their past whereas literate ones are constrained by what is recorded, especially if it’s Holy Writ (though it seems to me that even Holy Writ is reinterpreted for each generation). With that given, he produced several examples of societies in which an effloresence of learning comes out of a recovery of old ideas: Sung China with Confucianism, ‘Abbasid Islam with its incorporation of the Classics, or even nineteenth-century Bengal with Sanskrit and Vedic literature (so he argued). The crucial element, he finished by arguing, is the openness of religion to innovation in the respective societies; it can enforce stasis in order to protect the status quo, or in the right frame of reform and renewal it can encourage progress by similarly advocating a return to the roots. The true benchmark of such a renaissance, therefore, is not literary output but scientific progress. (The technology of communication is also a factor—for example, the ‘Abbasid revolution was made far easier by access to paper, so much cheaper than parchment—but less significantly.)

It is possible that I do Professor Goody an injustice with this summary, because he was as I say quite hard to hear properly. I am conscious that I may have filled in gaps in my understanding of his argument myself, so I’m not going to critique, merely report with that caution. Professor Burke, as a friend of Goody’s but one not afraid to argue with him, picked two things to react to: firstly, that Burckhardt’s picture of the Italian Renaissance, which Goody had mentioned, is now deprecated in favour of a continuity from Middle Ages to Industrial Revolution in the context of which the Renaissance has to be placed, and that it is no longer regarded as the single such group of changes even in the Western European context; but secondly, that he felt nonetheless that it was still exceptional in terms of scale, the number of people involved (or, I thought, known to have been involved) and range of disciplines and skills active exceeding those other European ones and even the non-European ones discussed by Goody. This is, he argued, why it remains the great comparator and the concept which is exported to other cultures to be tested against their conceptions of cultural change.

I shall not finish the rock band analogy I’ve started here. Professor Goody is indubitably a rock star in his discipline, and has provoked a great many discussions and arguments, as well as written, as Burke pointed out, on an incredible range of topics. If he genuinely were a seventies rock band I’d be damn impressed he had a new album out at all, and I’d have gone to the gig whatever it was likely to be like, just to say I’d seen him. It’s just that, as I say, the metrics by which I measure those performances are not ones I usually expect to be reminded of in this sphere.

1. Except, arguably, those by Status Quo. I don’t mean to demean this; they know exactly what their fans want and they provide.

2. Maria Lucía Pallares-Burke (ed.), The New History: confessions and conversations (Cambridge 2004).

3. J. Goody, Renaissances: the one or the many? (Cambridge 2010).

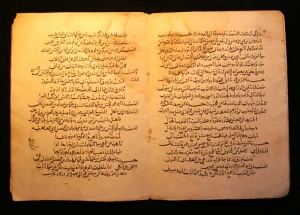

![IMGP1193 [800x600] Dave Brock of Hawkwind playing at the Cambridge Junction, December 2009](https://tenthmedieval.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/imgp1193-800x600.jpg?w=88&h=96)

Eech. As someone who has the dubious pleasure of trudging through Professor Goody’s by-now-well-matured arguments about food and cuisine, I have mixed feelings about the fact that he is still active among us (not in a still-alive sense, obviously, more in a still-active-on-the-lecture-circuit sense). He’s one of the greats, no doubt, but I can assure you that it’s as much of a labour to read his work as to listen to him, cough sweet or no.

Well, I have to admit that I’m not going to seek out the new book on the basis of this talk. I still have to face up to his Development of the Family and Marriage at some point, however, that being where he has got most medieval.

Pingback: First Trip to China, V: medieval Xí’án | A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe