Continuing the press through my reporting backlog, we now reach the third day of the 2015 International Congress on Medieval Studies, or as it’s otherwise known, Kalamazoo, 16th May 2015. Time is as ever short and the subject matter ageing, so I shall try and just do my brief list-and-comment format and I’m happy to provide more if they tweak people’s interest. But this is what I saw and some of what I thought…

Early Medieval Europe III

Obviously not one I could miss, given the participants:

- Eric J. Goldberg, “The Hunting Death of King Carloman II (884)”

- Cullen J. Chandler, “Nationalism and the Late Carolingian March”

- Phyllis Jestice, “When Duchesses Were Dukes: female dukes and the rhetoric of power in tenth-century Germany

Professor Goldberg made a good attempt to rehabilitate the reputation of King Carloman II, who did indeed get himself killed in a boar-hunt thereby wrecking Western Francia’s chance of Carolingian security, but who had also received the text of advice we know as the De Ordine Palatii from Archbishop Hincmar of Rheims and the acts of whose single council speak in moralising terms of reform and a return to old law in a way that suggests he had taken it to heart, and intended to rule like the right sort of king had the boar not won in one of the court’s fairly essential mutual displays of valour; it might justly be noted, as did Professor Goldberg, that the hunt was happening on a royal estate freshly recovered from the Vikings. As usual, it turns out not to be simple. Cullen made a fresh attempt at explaining the details of Count-Marquis Borrell II‘s undesired escape from Frankish over-rule in the years 985-987 without the national determinism that the standard Catalan scholarship has attached to those events, painting Borrell’s position as one of local legitimacy via multiple fidelities to powerful rulers rather than independència; I might not quite agree, preferring to see something like a serial monogamous Königsfern (to use Cullen’s own concept), but there’s no doubt that nationalism distorts all our perspectives.1 Lastly Professor Jestice looked at three German noblewomen, Judith Duchess of Burgundy, Beatrice Duchess of Upper Lotharingia and Hedwig Duchess of Swabia, over the 960s to 980s, during which time all of them were in various ways in charge of their duchies in the absence of an adult male ruler, and who were all addressed as dux, ‘duke’ as we translate it, in the masculine, in that time, and were awarded charters and held courts like the rulers in whose places we usually consider them to have stood. As Professor Jestice said, it’s a lot easier just to say that they exercised power in their own right, isn’t it? After all, when Duke Dietrich of Lotharingia threw his mother out of power, the pope imposed a penance on him, so you have to wonder if their categories were where we expect them to be. Questions here were mainly about the gendering of the language, and whether it actually has significance, but the point is surely that we can’t mark a clear difference between these women and their male counterparts, so should maybe stop doing it.

432. Money in the Middle Ages

Another obviously-required choice, with later ramifications I couldn’t have anticipated.

- Andrei Gândilâ, “Modern Money in a Pre-Modern Economy: Fiduciary Coinage in Early Byzantium”

- Lee Mordechai, “East Roman Imperial Spending and the Eleventh-Century Crisis”

- Lisa Wolverton, “War, Politics, and the Flow of Cash on the German-Czech-Polish Frontier”

Andrei opened up a question I have since pursued with him in other places (thanks not least to Lee, it’s all very circular), which is, how was Byzantine small change valued? From Anastasius (491-518) until the mid-ninth century Byzantine copper-alloy coinage usually carried a face value, which related to the gold coinage in which tax and military salaries were paid in ways we are occasionally told about, but its size didn’t just vary widely, with old 20-nummi pieces sometimes being bigger than newer 40-nummi ones, but was occasionally increased or restored, while old Roman and Byzantine bronze coins continued to run alongside this stuff in circulation at values we don’t understand.2 It seems obvious that the state could set the value of these coinages in ways that look very modern, but the supporting economic framework is largely invisible to us as yet. Lee, meanwhile, retold the economic history of the eleventh-century Byzantine empire, which is as he observed often graphed by means of tracking gold fineness, but could instead be seen as a series of policy reversals by very short-lived emperors that only Alexios I Komnenos, hero of that particular narrative, even had time to address in a way that had a chance of lasting.3 Lastly Professor Wolverton pointed at how often money was involved in the making and breaking of relations across her chosen frontier and argued that more should be done with this by historians, with which I am certainly not going to argue, although discussion made it seem as if the first problem is going to be the numbers provided by her sources.

Then coffee, much needed, and to the next building for…

472. Rethinking Medieval Maps

- Rebecca Darley, “Eating the Edge of the World in Book Eleven of the Christian Topography“

- Thomas Franke, “Exceeding Expectations: appeasement and subversion in the Catalan Atlas (1375)”

- Chet Van Duzer, “A Neglected Type of Mappamundi and its Re-Imaging in the Mare Historiarum (BnF MS Lat. 4995, fo. 26v)”

- Anne Derbes, “Rethinking Maps in Late Medieval Italy: Giusto de’ Menabodi’s Creation of the World in the Baptistery of Padua”

Most of this session was somewhat late for me, though not uninteresting, but as keen readers will know Rebecca Darley’s research just about meets mine at Byzantium. She was here arguing in general that, in the early Middle Ages, maps were not tools to be used to find things but ways of imaging space that could not actually be experienced, and used the sixth-century Alexandrian text known as the Christian Topography as an example. It argues in ten books for a flat world the shape of the Tabernacle but then apparently adding an eleventh using quite different source materials to describe the voyage by sea to India and Sri Lanka, with details of the animals from there that the author had seen or indeed eaten. The thing is that the book’s earlier maps don’t show India or Sri Lanka at all, and the cited animals and foods make it seem that the author wasn’t at all clear where they really were; they were not abstract enough to be mapped, but could be directly experienced. QED!

The world map from the Christian Topography of Cosmas. “WorldMapCosmasIndicopleustes” by Cosmas Indicopleustes, 6th century – “Les Sciences au Moyen-Age”, “Pour la Science”. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

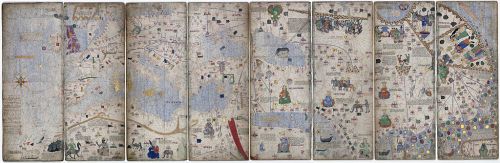

Then Mr Franke introduced us, or at least me, to the Catalan Atlas, a world map made by a Jewish artist for King Peter III or Aragón in 1375 which, according to Mr Franke, encodes in its numerous labels of sacred and indeed Apocalyptic locations and portrayals of their associated persons a message that Antichrist will look like the real Christ and that Jews will not be associated with him.

An eight-page montage of the Catalan Atlas in its Paris manuscript, by Abraham Cresques – Bibliothèque Nationale de Fance, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41309380

Mr Van Duzer, for his part, introduced us to another map-as-conceptual-diagram, not the well-known T-O map but a sort of V-in-a-box that shows the different destinations of the sons of Noah about the continents as per the Bible, developed and more less forgotten in the seventh century but revived in his fourteenth-century example manuscript as a vertical projection of a curved Earth, all of which together is more or less unparalleled.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Lat 4915, fo. 26v, showing the division of the world between the races

Lastly Professor Derbes described a world map that can be found in the sixteenth-century baptistery of Padua built by the Carrara family as part of a larger effort of showing off the learning and artistry which they could command. As with much of the session, all I could do with this was nod and enjoy the pictures but the pictures were all pretty good.

And that was it for the third day of papers. Once again, I didn’t do any of the evening sessions but instead hunted dinner in Kalamazoo proper, which the waiter told us was among other things the first home of the Gibson Les Paul guitar. This also means I missed the dance, which is becoming something of a worrying conference trend and perhaps something I should combat, at Kalamazoo at least, but by now I needed the rest, and so this day also wound down.

1. Until Cullen has this in print, one can see Paul Freedman making some of the same points more gently (because of being in Barcelona to do it) in his ‘Symbolic implications of the events of 985-988’ in Federico Udina i Martorell (ed.), Symposium internacional sobre els orígens de Catalunya (segles VIII-IX), 2 vols (Barcelona 1991-1992), also published as Memorias de la Real Academia de Buenas Letras de Barcelona Vols 23-24 (Barcelona 1991-1992), I pp. 117-129, online here.

2. The current state of the art on this question is more or less one article, Cécile Morrisson, “La monnaie fiduciaire à Byzance ou ‘Vraie monnaie’, ‘monnaie fiduciaire’ et ‘fausse monnaie’ à Byzance” in Bulletin de la Société Française de Numismatique Vol. 34 (Paris 1979), pp. 612-616.